LIBRARY OF CONGRESS…

Yet another victim of current presidential administration chicanery – in addition to the NEA as noted below – is the Library of Congress. Not only was the distinguished immediate past Librarian of Congress, the distinguished Dr. Carla Hayden dismissed and replaced by a thoroughly unqualified MAGA toady, but as of this date (October 21, 2025) the Library of Congress is essentially shuttered as a result of the unconscionable government shut-down with no end in sight.

So for those who may have missed my talk as Jazz Scholar in Residence at the Library of Congress, here are my remarks from my Wednesday, June 18, 2025 talk at the LOC, which preceded an exceptional concert performance by NEA Jazz Master Gary Bartz:

Willard Jenkins Library of Congress Talk

Last Winter I was delighted to be selected as a Jazz Scholar for 2025. In subsequent weeks leading up to my LOC talk on Wednesday, June 18 – as a pre-concert conversation to that evening’s performance by NEA Jazz Master Gary Bartz – I spent some very valuable hours examining some of the LOC’s vast jazz Collections. Here’s my report from that wonderful experience.

As Jazz Scholar at the Library Of Congress, I eagerly got busy investigating their jazz collections assets through their online resources. Many of the resources within those collections are music scores, composition lead sheets, arrangements, transcriptions, assets I refer to as the science of music side of these great artists’ careers.

Further investigations of LOC Jazz Collections online led me to invaluable details of the contents of each of their jazz collections, including a very responsive query function, enabling researchers and the purely inquisitive to focus on a single or specific resources in those collections .

I eagerly made my initial research visit to the Reading Room at the Madison Building in early March. On arrival I was met by my guide on this journey, Claudia Morales, LOC concert producer, and an invaluable liaison to whom I owe a great debt of gratitude. After a detailed orientation, Claudia displayed a box from the Wayne Shorter Collection exemplifying the LOC’s jazz collection resources.

I was delighted to discover dozens of Wayne Shorter’s lead sheets, arrangements, and scores to several of his extended compositions… all apparently written in his own hand! I found myself humming Wayne Shorter themes – including from Wayne’s formative days with Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, his subsequent Blue Note recordings, and from Wayne’s Weather Report work.

What was someone like me to make of these vast resources, someone largely untrained in the technical aspect of music? How was I to report on what appeared to my untrained eyes as sheets and sheets of pure hieroglyphics? As I did a deeper dive into the list of the LOC’s jazz collections, having seen the February 21st PBS American Masters series documentary on pianist & vocalist Hazel Scott, my eyes landed on her entry among the LOC’s jazz collections.

I quickly requested some of Scott’s cartons! As I leafed through the Hazel Scott Collection it became clear that this LOC residency would be a masterclass experience, even for a non-musician like myself, but someone who has otherwise been deeply immersed in this music. How could I make this a truly substantive experience, AND have something to report on what I actually discovered during this appointment?

Initially I examined the Hazel Scott, Dexter Gordon, and Max Roach Collections. Throughout the Hazel Scott Collection it became clear that Hazel was not only an incredible musician, she was also quite the Race Woman. I found her essay titled “Message To Young Black People”. I also found essays she had written about “Brother Malcolm” (Malcolm X), and Martin Luther King Jr. among others.

From the Max Roach Collection I found fliers advertising performances of his classic Freedom Now: We Insist suite – including fliers advertising performances to benefit the NAACP, and another for CORE. Max Roach was also a ‘Race Man’ of the first order. I discovered a warm hand-written letter to Max from Eldridge Cleaver, of the Black Panther Party.

At one point the great poet Amiri Baraka worked with Max on his memoirs. I found interview transcripts and un-published memoir manuscripts from Baraka’s effort, which sadly never reached fruition. I was likewise fascinated by a detailed Max Roach budget sheet for a production of his Freedom Now Suite. I found several very loving letters Maya Angelou wrote to Max and Abbey Lincoln in the Collection, with the salutation “Dear Abbey Max” as though they were inseparable in their artistic quest.

In the Dexter Gordon Collection I came upon an essay he wrote,“Dexter Gordon: On Arriving in New York – January 1941”, doubtless employed by Dexter’s widow, Maxine Gordon for her masterful 2016 Dexter biography Sophisticated Giant. Going through the Collections of such giants as Hazel Scott, Max Roach, and Dexter Gordon was riveting.

It was truly a thrill receiving the 2024 National Endowment for the Arts A.B. Spellman Jazz Master’s Fellowship for Advocacy award. The more I thought about that the more I began to focus on jazz advocacy as I visited those LOC Jazz Collections. Further examining the list of jazz greats whose collections were bequeathed to the LOC, my eyes fell on the names of those who had not only been great musicians and composers, but who had also worked tirelessly as jazz advocates.

Max Roach was a tireless advocate for Black people, and the same held true for Hazel Scott. Another who was a great advocate on behalf of jazz musicians throughout his career was the Record Man, Bruce Lundvall, whose last station in the record industry was reviving the historic Blue Note Records label. In the annals of jazz, many so-called Record Men, primarily industry executives, had unsavory reputations among musicians – particularly Black musicians – as essentially slave drivers, veritable Simon Legrees. That was not the case with Lundvall, who had a sterling reputation among musicians Black, White and otherwise, attested to by materials in his LOC Collection. Leafing through the Lundvall Collection I came across warmly conveyed letters from such giants as Quincy Jones, Chick Corea, and Benny Golson. I was also inevitably drawn to documents related to Bruce’s experiences recording Miles Davis for CBS Records.

Then I spotted a name on the list of Library of Congress Collections that resonated with me, someone who’d been a tireless jazz advocate from so many directions. Someone who’d been incredibly supportive of my own advocacy work. Someone I’d interacted with during my relatively short time as executive director of the National Jazz Service Organization. Someone who’d been not only musician-composer-bandleader, but who’d also worked his jazz advocacy magic on radio, television, in the classroom, and as jazz presenter. Someone whose concerts I’d attended religiously at the Kennedy Center, and someone with a great feeling for Washington. That would be the great Dr. Billy Taylor. After a few research visits to the first floor Reading Room in the Library of Congress’ Madison Building, I largely concentrated my investigation on the voluminous Collection of Dr. Billy Taylor. As the late jazz critic Leonard Feather once said, “It is almost indisputable that Dr. Billy Taylor is the world’s foremost spokesman for jazz.”

My jazz radio broadcasting began in 1972 as a student at Kent State University, continuing today in DC at WPFW 89.3FM. Billy Taylor had worked as a jazz DJ and program director at WLIB in New York City. I spent 10 years doing jazz television for the former BET On Jazz. In 1958 Billy became music director of NBC’s The Subject of Jazz, then went on famously as the bandleader on the David Frost Show from 1969-1972, and later as correspondent on the CBS Sunday Morning show with Charles Kuralt, conducting over 250 interviews with musicians, the great majority of which were jazz artists.

My jazz presenting efforts began at the Northeast Ohio Jazz Society in the late 1970s. I worked as a jazz advocate/arts administrator at Arts Midwest in Minneapolis until 1989, at which point we relocated to DC, as executive director of the former National Jazz Service Organization, with Billy Taylor on the Board. So the sense of jazz advocacy parallels – mine on a much more modest scale – were obvious, not to mention both of our many writings on jazz.

The Billy Taylor Collection houses great detail on his radio career advocating for jazz, including his Jazz Alive! series for National Public Radio. Prior to that, Billy had morphed his jazz piano history book into a radio series bent on demystifying jazz and it’s history for the masses. The more I examined his papers the deeper and broader his advocacy efforts clarified on behalf of jazz music, its musicians, its audience, Billy’s subsequent influence became even clearer. When you listen now to satellite radio on SiriusXM and hear their Real Jazz channel you’ll hear specialty programs from such masters as bassists Christian McBride and Marcus Miller, drummer Terri Lyne Carrington, and organist Pat Bianchi. Clearly Dr. Billy Taylor paved the way for them.

In 1995 Billy Taylor launched Billy Taylor’s Jazz at the Kennedy Center. That series proved to be a masterful jazz advocacy effort. Billy engaged guest artists with his trio in a format where they played some and talked some in a manner that further de-mystifyed jazz music for audiences, providing insights into how the music is made and why the musicians make certain musical choices. I quickly learned that in typical Billy Taylor fashion, this was an extraordinarily well-plotted series, not some seat-of-the-pants quasi jam session with friends. I found cue sheets in the Collection, among them detailing the plots for shows with violin great and NEA Jazz Master Regina Carter, another plotting a show featuring NEA Jazz Master alto saxophonist-educator Jackie McLean, just to give a sense of the range of artists Billy invited to encounter onstage at the KC’s Terrace Theatre.

I found the Reading Room personnel to be quite friendly and cooperative, and here I have to say a special thanks particularly to the reference librarian Morgan Davis. I’d communicate my research interests to Claudia, and later to Morgan, and without fail the materials I requested from the various collections would be there on my arrival. That was my journey through the Jazz Collection resources at the Library of Congress… for now!

Willard Jenkins

Artistic Director

DC Jazz Festival

In light of the very troubling moment we find ourselves in relative to the current administration’s goal of emasculating American culture in their own image, I must ask: Has the NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship program been completely eliminated? I ask this out of consideration that having so happily experienced that award and all of the subsequent protocol, we still have no idea whether the program will continue or if there was even a 2025 class of NEA Jazz Masters selected!

I learned of my own selection to the 2024 class of NEA Jazz Masters, along with NEAJMs Terence Blanchard, Gary Bartz, and Amina Claudine Myers – me having been selected as that year’s A.B. Spellman NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship for Advocacy – way back on the day after Easter 2024! The subsequent schedule of events went this way:

- Public announcement in July, 2024

- NEA Jazz Masters awards events: April, 2024

As of Fall, 2025 there has been no announcement of a 2025 NEAJM class. Troubling and deeply saddening indeed. Reminiscing about my whole experience, I’m posting the subsequent National Endowment for the Arts podcast I participated in when I was humbly selected here; thanks to the intrepid Josphine Reed, my former WPFW colleague who fortunately for her retired from the NEA in advance of the current pinheads’ occupying our current administration:

https://www.arts.gov/stories/podcast/willard-jenkins

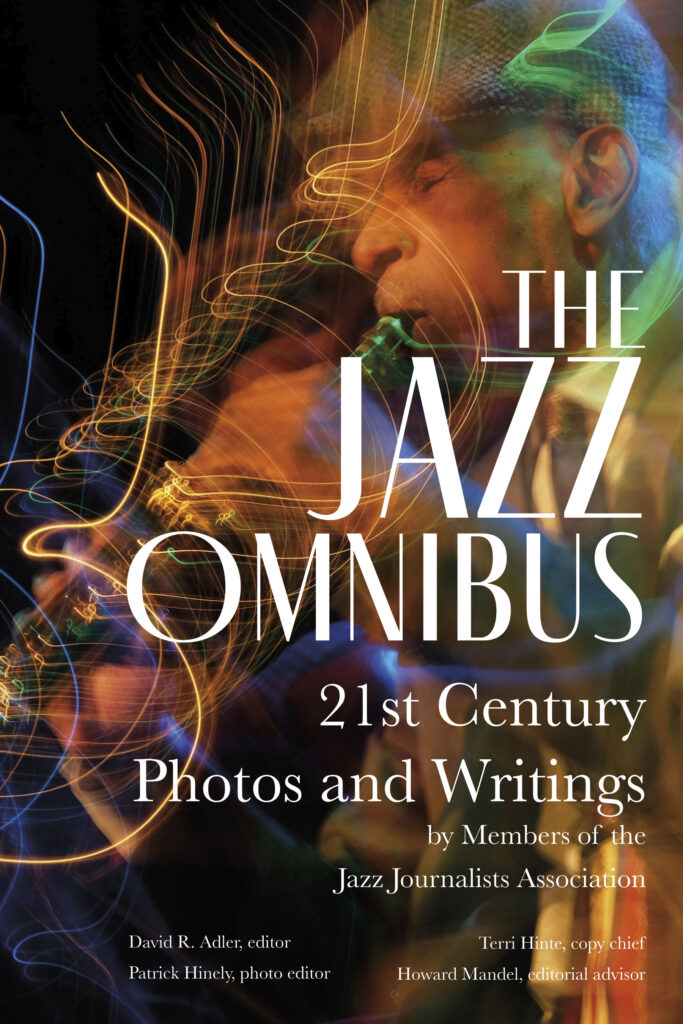

It’s here! The Jazz Omnibus – 21st-Century photos and writings by JJA members!

by JJA Editor

October 27, 2024

Announcing The Jazz Omnibus: 21st-Century Photos and Writings by Members of the Jazz Journalists Association, a unique anthology being published in ebook and print-on-demand paperback and hardcover editions on October 15 by Cymbal Press.

For the first time ever, the JJA has merch! Vivid Jazz Omnibus t-shirts (Tangible Sound cover photo of Roscoe Mitchell by Lauren Deutsch) are as low as $16. Phone cases, tote bags, stickers, mugs, hats, etc… are also available at a 35% sale at TeePublic.

A team effort featuring 90 contributors, compiled by editor David Adler, photography editor Patrick Hinely, copy chief Terri Hinte and editorial consultant Howard Mandel with Fiona Ross and Martin Johnson as submission readers, The Jazz Omnibus is dedicated to the memory of jazz scholar and chronicler Dan Morgenstern (1929-2024). The 600-page volume features 69 articles, 23 black and white photos, and an extensive selected bibliography. It is currently available for pre-publication orders in all formats at Amazon.com and directly from Cymbal Press.

Sponsors underwriting the book’s promotion include Berklee School of Music’s Institute for Jazz and Gender Justice; Impulse!, Verve and Blue Note Records; and the Jazz Foundation of America; funds from sales will contribute to covering the non-profit, membership-supported JJA’s general operating expenses.

The Jazz Omnibus is unrivaled as a collection self-selected “best works” by the far-flung members of the JJA, ]including international reports, interviews with major figures, profiles of emerging artists, biographical and analytical essays, memoirs and reviews, portraits and action photography.

Wide in scope, The Jazz Omnibus includes among its many highlights:

- an up-close and personal hang with Sonny Rollins by Ted Panken;

- probing interview with Keith Jarrett by Michael Jackson;

- appreciation of Carla Bley by Suzanne Lorge;

- conversation with Wynton Marsalis by Doug Hall;

- Leslie Pintchik on the thrills of performing, “In Play”;

- re-appraisals of Amy Winehouse by Ted Gioia and Sun Ra by Nate Chinen;

- excerpts of Deanna Witkowski’s Mary Louis Williams: Music for the Soul, Willard Jenkins’ Aint But a Few of Us and Mike Longo’s memoirs, in his voice by his widow Dorothy Longo;

- Mirian Arbalejo’s impassioned declaration “I Do Write So Let Me Write”;

- George Wein’s obituary by Peter Keepnews;

- Ashley Kahn’s award-winning “The New Jazz Emigrés” on American musicians in Europe today.

Cultivating the Next Generation of Jazz: A Message from Heidi Martin

If the next Duke Ellington or Ella Fitzgerald emerges in the coming years, they may very well come from the vibrant year-round programs of DC Jazz Festival Education!

Our mission, beyond teaching jazz, is to nurture lifelong learners while fostering a love for this rich art form. “From our youngest participants to aspiring professionals, we are building skills, confidence, and connection to the incredible jazz legacy that belongs to all of us,” said DC Jazz Festival CEO Sunny Sumter.

This year, one of our cornerstone programs, DC Jazz Bops! introduces pre-K through 2nd-grade students to jazz through engaging storybooks, rhythmic exercises, and playful activities. Taught by me in my teaching artist role, these sessions don’t just promote literacy and math skills—they inspire students to discover their voice and confidence through music. Our theme song says it best: “We sing, we swing, we sway Clavé! The music, it never stops! Our elders live on in every note they wrote, because DC Jazz Bops! We are DC Jazz Bops!”

For older students, Jazzin’ AfterSchool, led by teaching artist Herman Burney, provided beginning students opportunity to play in an ensemble and a showcase concert where students perform for family and friends. Similarly, our Beginning Guitar Program flourished in underserved communities across Wards 7 and 8, introducing students to the joys of music-making in a supportive, hands-on environment.

We were also thrilled to announce the launch of the JazzDC Youth Ensemble, in partnership with Sitar Arts Center and DC Youth Orchestra. Led by saxophonist Elijah Balbed, this audition-based ensemble provides serious young players in the DC area with mentorship and performance opportunities, preparing them for professional music careers.

Our Jazzin’ InSchool Field Trip Initiative, with major support from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, brought live jazz directly to students. With professional musicians like Artist in Residence Corcoran Holt and percussionist Pedrito Martinez leading the way, International Rhythms of Jazz—From Clave to Afro-Pop! engaged students through music and storytelling, often providing their first opportunity to experience live jazz.

During our annual DC JazzFest, our education team hosted Meet the Artist interviews. Conversations with NEA Jazz Masters like Artist-in-Residence Ron Carter, DownBeat blindfold test with Stanley Clarke, DCJazzPrix winner Hiruy Tirfe Quartet, and Terri Lyne Carrington on her New Standards Exhibit gave festivalgoers an intimate opportunity to connect with both legendary and emerging artists. With six youth ensembles in performance during DC JazzFest, we bridged generations and celebrated the continuum of jazz. And, thanks to Amazon, we provided 1,827 DC JazzFest tickets, free-of-charge to our DC public and charter school students, teachers and their families.

All education programs are led by jazz professionals, with a substantial amount of DCJF Education covered thanks to the generosity of foundations like the Galena Yorktown Foundation, the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, Venable Foundation, Ella Fitzgerald Foundation, Les Paul Foundation, and individual and community donors like you. If you haven’t yet contributed to this year’s education programs, there’s still time to make a difference. Your donation fuels the next generation of jazz musicians and ensures that these programs remain accessible to all.

Thank you for believing in the power of jazz education to transform lives. Together, we are preserving the past, inspiring the present, and building the future of jazz.

With gratitude,

Heidi Martin

Manager, Education and Outreach

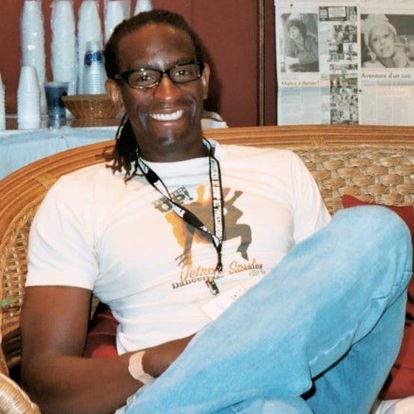

NEA Announces the 2024 Recipients of NEA Jazz Masters Honors

Recipients Honored April 13, 2024, at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC

Jul 12, 2023

Washington, DC—Continuing its more than 40-year history of honoring individuals who have made exceptional contributions to the advancement of jazz, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) today announced the 2024 recipients of NEA Jazz Masters Fellowships—Gary Bartz, Terence Blanchard, Amina Claudine Myers, and Willard Jenkins, recipient of the 2024 A.B. Spellman NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship for Jazz Advocacy. These fellowships include an award of $25,000 and the honorees will be celebrated at a free concert in Washington, DC, on Saturday, April 13, 2024, in collaboration with the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

“Jazz is one of our nation’s most significant artistic contributions to the world, and the NEA is proud to recognize individuals whose creativity and dedication ensure that the art form continues to evolve and inspire new audiences and practitioners,” said NEA Chair Maria Rosario Jackson, PhD. “We are thrilled to collaborate with the Kennedy Center again this year on a concert that will honor and celebrate these Jazz Masters’ contributions and the importance of jazz.”

Gary Bartz has been one of the best purveyors of what he calls “informal composition” (as opposed to improvisation) on alto saxophone since the 1960s, working with such luminaries as Max Roach, Charles Mingus, Art Blakey, and Miles Davis. He has released more than 45 solo albums and appears on more than 200 as a guest artist, as well as working with some of the up-and-coming artists in jazz today.

Terence Blanchard is a seven-time Grammy Award-winner who has been a consistent artistic force for making powerful musical statements for over 40 years. From his stint with Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers to writing scores for Spike Lee and others, he is unique in the jazz world as an artist whose creative endeavors go far beyond the genre into composing music for television and film, conceiving grand operas, and collaborating with dance companies.

From her early beginnings as a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), Amina Claudine Myers has gained acclaim as a skilled composer for voice and instruments, often displaying her gospel influences. Her move to New York City in the 1970s led her to prioritize her compositional work and to take on theatrical production projects.

Willard Jenkins has been involved in jazz as a writer, broadcaster, educator, historian, artistic director and arts consultant since the 1970s and is one of the major voices in promulgating the music and its importance to American culture. Currently the artistic director of the DC Jazz Festival and host of the Ancient/Future program on DC’s WPFW radio station, Jenkins is an authority on the local as well as national jazz scene. Jenkins is the 2024 recipient of the A.B. Spellman NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship for Jazz Advocacy given to those who have made major contributions to the appreciation, knowledge, and advancement of the American jazz art form.

More information on the 2024 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert, including how to reserve free tickets and watch the live webcast, will be available early next year. Past NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concerts are available to view on the NEA’s YouTube page.

“What a thrill to again bring the NEA Jazz Masters back to the Kennedy Center and have this particular class of greats honored at our National Cultural Center,” said Jason Moran, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. “Gary Bartz’s saxophone has blazed trails with his dynamic phraseology and iconic tone for decades—he is representative for the truth in music; Terence Blanchard does it all, from the trumpet to the screen with a singular genius; Amina Claudine Myers has devoted endless time and energy to creating a new canon in the AACM, and when she’s at the keys, soul pours freely from her voice and fingers; and Willard Jenkins has wielded his pen to be a passionate amplifier for the music and the musician.”

Visit arts.gov for longer bios and selected discographies of the 2024 NEA Jazz Masters. High-resolution photos of the 2024 NEA Jazz Masters are available for media use.

About the NEA Jazz Masters

Since 1982, the National Endowment for the Arts has awarded 173 fellowships to great figures in jazz, such as Toshiko Akiyoshi, Regina Carter, Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Donald Harrison, Jr., Yusef Lateef, Abbey Lincoln, Sue Mingus, Eddie Palmieri, Sonny Rollins, and Wayne Shorter. Explore the NEA’s website for photos and bios of all of the NEA Jazz Masters, as well as archived concerts, video tributes, podcasts, and more than 350 NEA Jazz Moments audio clips. The National Endowment for the Arts has also supported the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program, an effort to document the lives and careers of nearly 100 NEA Jazz Masters.

Nominate an NEA Jazz Master:

The NEA Jazz Masters Fellowships are awarded to living individuals on the basis of nominations from the public including members of the jazz community. NEA Jazz Masters Fellowships are up to $25,000 and can be received once in a lifetime. Visit the NEA’s website for detailed information and to submit nominations. The deadline for nominations for the next class of honorees is October 31, 2023.

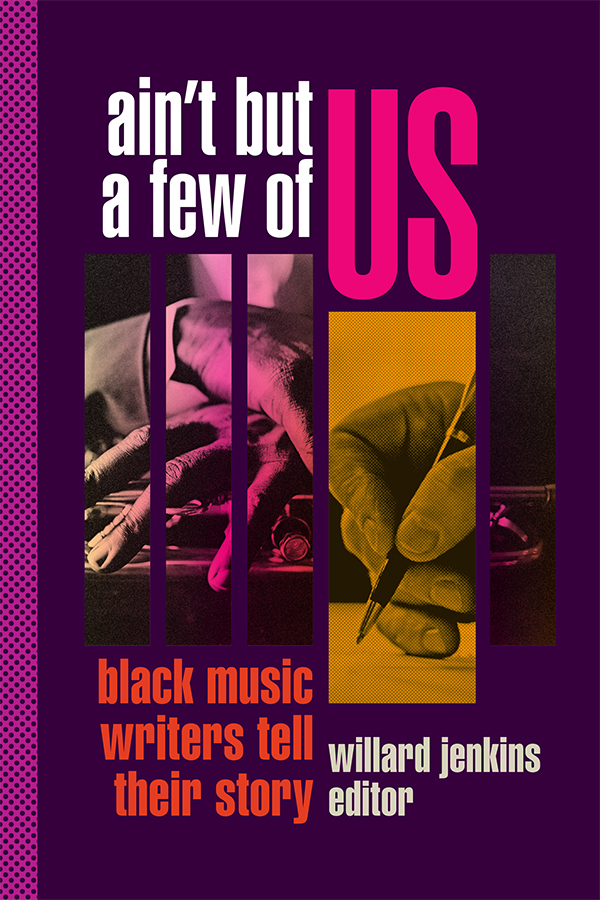

Ain’t But a Few of Us

“Ain’t But A Few of Us” rings true for journalists of color within the realm of Jazz coverage. Jazz is an art form that was born out of the African American experience of social struggle and artistic innovation. But since Jazz was first popularized, the bulk of news coverage, commentary, academic study and critique has been recorded for posterity by white writers. Whether this is due to cultural bias, a lack of opportunities for writers of color, or an overall lack of interest in Jazz coverage by most popular media is still unclear to me. But the few of us who are here — the journalists of color covering the Jazz scene because we love the music, the musicians, the history and the culture — are working to have our words read and our voices heard. That’s why this new anthology by Willard Jenkins is so critical. While “ain’t but a few of us” may sound like a complaint, it’s really a banner of pride and a rallying cry by a community looking to expand its ranks. That’s what the phrase means to me.

- Janine Coveney, Contributor; Writer: Jazz Awards

PURCHASE LINK:

https://www.dukeupress.edu/aint-but-a-few-of-us

Discount purchase offer: 30% off coupon code which will never expire: E22JNKNS

INTRODUCTION

This book is comprised of an unprecedented series of dialogues with Black jazz writers, focused mainly on their respective writing career arcs, often touching on the vexing challenges of race – that man-made construct that continues to plague all of humanity. Race – or implications of racism – is frequently at the root of African American music writer’s struggles with access.

A contributor to this dialogue, the journalist-editor-educator Ron Welburn, asserted in the 1987 Volume 7 issue of BMR Journal (published by the Center for Black Music Research at Columbia College, Chicago) that African American proto-jazz pioneer James Reese Europe was the original jazz critic, among his immense contributions as musician, military man, and one of the primary early exporters of the jazz sound to Europe via his military service. Of Europe, Welburn wrote: “His role and place in the development of genuine jazz criticism is important given that he himself was not a writer-journalist. When the newspapers quoted him on Negro dance and symphonic music, his articulate descriptions and reasoning served the new music well by elevating it in the minds of his readers and by establishing a paradigm for later jazz criticism.” Another Welburn citation was Europe’s last published interview, for the New York Tribune (March, 1919), titled “A Negro Explains Jazz.”

Contrast Ron Welburn’s assertion with the more popularly historic citation of Paris-born dancer-choreographer-writer Roger Pryor Dodge (1898-1974) as perhaps the original jazz critic. Dodge, whose writings span the early 20s to 1964, published his first piece a critique of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in, in 1924. His first real jazz criticism came in a 1925 piece titled “Jazz Contra Whiteman,” which was curiously retitled “Negro Jazz” in a 1929 reprint in the British publication The Dancing Times. Dodge achieved a distinguished career in dance and music criticism, including his late career considerations of “modern” jazz, the bebop era.

Consideration of James Reese Europe’s historical precedents aside, jazz journalism and criticism has overwhelmingly been the province of white men. Author Gerald Horne’s recent book Jazz and Justice cites the distinguished jazz critic-record producer Nat Hentoff’s assertion that his 1950s era firing from the staff of DownBeat magazine, which Horne refers to as “the bible of the business”, had to do with management bias against Jews and Blacks. “I did something that led to my termination, I wondered why we didn’t have any black people on the staff… I never saw a black by-line on the magazine.”

Despite the origin of jazz as a largely urban phenomenon (at its core, jazz is Great Black Music, as the Art Ensemble of Chicago postulated), and the daily newspaper as the historic conveyor of news and information in the cities, jazz journalism and criticism in that medium has been almost exclusively a whitewash. “Astonishing and ironic as it sounds, there is now no Afro American critic or commentator of [jazz] in any of the major U.S. newspapers.” [Amiri Baraka, October 31, 1998 address to the JazzTimes Convention] “Can you believe the second essay I had published in the old Jazz Review said the same thing,” referring to his classic article “Jazz & The White Critic” [1958].” That article served as a partial stimulus for this book and its series of dialogues. And 62 years later, that observation remains salient!

This book is important on many levels: It refutes the long-held belief that there is no significant potpourri of African American writers on jazz; it reveals the wide range of thought, method, analysis and historiography expressed by those writers and it preserves the philosophies and opinions of several writers who sadly, are no longer with us. Bravo Mr. Jenkins for this extraordinary compendium!

- Eugene Holley, Contributor

In his chapter, writer-musician, and founder of the Black Rock Coalition, Greg Tate observes specifically about the #1 daily serving New York City, also known as the mythical jazz mecca. In the aggregate the New York Times has arguably provided more jazz coverage than practically any other mainstream daily, though the Chicago Tribune might legitimately argue that point. “The New York Times still has never had a regular Black jazz writer,” observes Tate.

The origin story of jazz music marks it as a distinct vehicle for Black self-expression. Jazz has been perhaps the most sophisticated Black originated musical medium of expression to transcend the man-made boundaries of race. Yet it’s principle criticism and journalism has come not from Black voices, but from White men. As one of the pioneers of Black jazz journalism, Amiri Baraka (whose writings on jazz commenced in the 1960s, roughly 40 years after Roger Pryor Dodge’s precedents) has written, “To think that only White men can have a profound or scholarly or analytical understanding of Afro American Music is disgusting and ignorant.”

The contributors to this book offer ample evidence of how Black jazz journalists arguably experience the music differently, through sundry elements of shared historiography with the great pioneers of this music, and their often common origin stories with the many Black contributors to contemporary jazz. Our contributors make a compelling case for the need for broader diversity and more Black bylines in the journalistic and critical response to jazz.

In her chapter Farah Jasmine Griffin, author of If You Can’t Be Free, Be a Mystery: In Search of Billie Holiday (2002; One World), speaks to her original compulsion to write on jazz: “[Musician friends] were encouraging me to [write about jazz] because there weren’t that many Black people writing about music, because so much of the writing about music was not really understanding the context out of which the music was emerging.” [Emphasis mine].

Ain’t But a Few of Us readers may surmise, in purely numerical terms, that there are certainly a fair number of African American music writers with jazz interests and acumen who’ve been published on jazz. However nagging issues of access have been a source of ongoing frustration in their various odysseys. You’ll learn that race – or insinuations of racism – is frequently at the root of their frustrations with access, be those frustrations real or perceived. You’ll learn of the struggles of achieving bylines for some Black writers who as recourse have turned to self-publishing the jazz prose they choose to write.

The historic scarcity of Black writers consistently covering a music which at its core is indisputably in very large measure a musical product of the African experience in America, is not a new observation, witness Baraka’s classic 1958 essay. In his June 5, 2020 online article (www.sopranosaxtalk.blogspot.com) Why are There so Few Black Writers in Jazz?, soprano saxophonist Sam Newsome contributed a very thoughtful essay on this subject.

Newsome writes “And let me be clear, many greats wrote extensively about jazz and jazz-laced topics: Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Albert Murray, Amiri Baraka, to name a few. And then there are the contemporary [Black] critics, essayists and historians like Stanley Crouch, Willard Jenkins, K. Leander Williams, Greg Tate, Greg Thomas, and Robin D.G. Kelley” [editor’s note: all but Crouch contributed dialogue to this book.] “Even though they’re not all in the same league, what they share is an unwavering love for the music. Nonetheless, it does prove my point that even though Black writers do exist in jazz, however by comparison to the number of [Black] performers, we are still relatively few.”

Newsome pointedly observed from his experience of attending the annual Jazz Journalist Association awards show, what a cursory scan of the audience that day at the Blue Note revealed to him, “…you could pretty much assume that the white males [in the audience] were journalists and the black males were musicians. These are the racially segregated teams that have played the proverbial game of jazz since the very beginning,” said the saxophonist.

“Having more of a presence of Black writers would offer a different sensibility that would broaden the aesthetical spectrum of these magazines, and not just cosmetic diversification, which is often the case with skin-based attempts at diversity like those seen at elite schools and universities.” Newsome goes on to hypothesize “…that there’s a certain cadence presence in black writers, which differs from that of white, Hispanic, and Asian writers. For some reason, acknowledging cultural and aesthetical differences between groups gets us labeled as racist. I think it’s more racist, pretending that no cultural differences exist in the arts.”

In his chapter, Bill Brower recalls reading the book Backstory in Blue: Duke Ellington at Newport ’56 (by John Fass Morton and Jonathan Yardley; Rutgers University Press 2008) detailing Duke Ellington’s famous 1956 Newport Jazz Festival performance. “The book talks about how that initial phase of jazz writers were all students who knew each other from these Ivy League schools and were avid record collectors,” details Brower. “They created a network of jazz writers and to a large degree I believe that network has been perpetuated over generations, and it has not encouraged African Americans to do that work. For the most part black writers that have written about the music have not been included in that network. We may have friends, we may have associations within that fraternity, but we’re really not in the inner sanctums of that fraternity.” Ain’t But a Few of Us provides clear proof that there are in fact a fair number of Black writers who’ve skillfully covered jazz and continue to have great interest in doing so.

The gatekeeping and erasure of Black voices in jazz journalism is a systemic issue in the jazz journalistic realm that needs to be addressed. The redirection of this issue, that is, restructuring the system to acknowledge is long overdue. Nonetheless, Willard has taken on the task with vigor and unrelenting persistence. As a Black jazz writer, I am thankful and honored to be included in the Black jazz journalism canon. He has written us into history. With humility and honor, I applaud those who have brought Ain’t But a Few of Us to fruition. The future, as a whole, will be better and hopeful now that our voices have been raised. Bless my mentor and friend, Greg Tate, and all those included in this collection.

Jordannah Elizabeth, Contributor

Considering Newsome’s suggestion that Black jazz writers would serve to broaden the discourse on jazz, one need look no further than a classic example of an otherwise honored jazz critic and record producer, the late Ira Gitler, who not long before his passing received a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters fellowship. In his notorious 1962 review of vocalist-lyricist Abbey Lincoln (likewise a NEA Jazz Master)’s album “Straight Ahead,” commenting on Ms. Lincoln’s race-pride expressions, Gitler referred to the singer thusly: “The [album liner] notes state that part of her liberation as a singer “has come from a renewed and urgent pride in myself as a Negro.” “The only trouble is that she has become a “professional Negro.” Would an African American writer have viewed Ms. Lincoln’s race pride in such calloused terms? Ain’t But a Few of Us readers will discover what has largely been missing in jazz journalism – black voices in the discourse.

The same question arises in response to other telling Gitler observations in his review. For example: “She is involved in African nationalism without realizing that the African Negro doesn’t give a fig for the American Negro, especially if they are not blackly authentic.” So exactly where did Ira Gitler acquire his black authenticity detector?

Gitler proceeds to postulate “Now that Abbey Lincoln has found herself as a Negro, I hope she can find herself as a militant, but less one-sided American Negro.” These observations beg the obvious question: would a Black jazz writer have judged Abbey Lincoln’s ideas and pursuits with such a stunning lack of sensitivity and insight?

Gitler’s review of Ms. Lincoln’s album raised such a firestorm for the magazine at the time that DownBeat brought together a subsequent panel discussion to ostensibly examine race matters in jazz. Invitees included Abbey, master drummer Max Roach (Ms. Lincoln’s spouse), white trumpeter Don Ellis, Argentinian pianist-composer Lalo Schiffrin, and jazz writer-record producer and political commentator Nat Hentoff, moderated by DB editors Bill Coss and Don DeMichael.

During the discussion (published in two parts beginning with the March 15, 1962 issue), Hentoff remarked: “Would not black jazz writers have on average a greater degree of empathy if not understanding of that coded language? Wouldn’t black writers be better equipped purely on the empathy if not understanding scale to sympathetically portray the lives and aspirations of their brother/sister musicians?” Ms. Lincoln opened the discussion with this observation of Gitler’s review: “Firstly, it was not a review of the music.” To which Roach cogently interjected: “And you can’t feel something that happened in the South, the way I feel it.” [emphasis mine].

If a white jazz composer chose to celebrate his or her Irish, Danish, German, Italian, Jewish, French or other heritage on record, would a black reviewer in Gitler’s position have shown the same blatant insensitivities? Lacking insidious white privilege, likely not.

It’s easy to navigate the cosmopolitan jazz world as “a loner,” when you’re a Black jazz journalist seeking other Black jazz journalists. This important book chronicles segments of our collective and individual journeys, while making it clear that we still have multiple systemic barriers to overcome.”

- John Murph, Contributor

This book, like none other previously, will explore angles of racial disparities in jazz media coverage, and the differing perspectives – and sensitivities – Black writers would likely have brought to such a review assignment. Ain’t But a Few of Us contributors offer examples and alternative sensibilities on how a white privileged writer so lacking in perspective on the Black experience as Ira Gitler clearly came up short in his patently unenlightened viewpoints of Ms. Lincoln’s work and posture.

In author Robin D.G. Kelley’s chapter he makes this cogent observation, “For many black intellectuals the music and the people, the music and the context, the music and the community (from whence they arrived) are inseparable. Once you separate these things, it is easy to make the case that jazz transcends race and history – it is a way of claiming jazz’s universalism, but based on a skewed definition of universal without connection.”

Amiri Baraka, in his 1998 JazzTimes Convention keynote address, issued this call to action, “I am urging the musicians and other progressives to get behind the production of new and alternative publications that give voice to a multinational diversely attitudinal stable of writers and opinions. Like Mao said, “Let a hundred flowers bloom, let a hundred schools of thought contend”. It can only broaden both the depth of understanding and the length of outreach of the art form itself. It will also enrich the scholarship and authenticity of analysis which can only benefit the entire international community.”

For the first time under one cover, this book will explore the challenges not only writers, but also African American editor/publishers faced in building and publishing their own Afrocentric jazz periodicals. We’ll take a peek inside their pages and hear from such intrepid souls as the late Jo Ann Cheatham (Pure Jazz Magazine), Jim Harrison (Jazz Spotlite News), Haybert Houston (Jazz Now), and Ron Welburn (The Grackle).

“I started [Jazz Spotlite News] to give black writers a place to write about the music,” remarked Jim Harrison during our interview. “Since I was involved in the jazz business I knew where the writers were, people that wanted to write. For many of these black writers they really hadn’t had opportunities to write for the other mainstream jazz magazines.”

By the same token, the so-called Black dispatch – local newspapers and periodicals, many of them historic (Amsterdam News, Pittsburgh Courier, Chicago Defender, etc. with currently 51 such publications still operating) published by and for African American readerships, has historically come up woefully short on jazz journalism. Archival research of many such publications reveals that, though there were rare exceptions, the historically scant jazz coverage in the Black dispatch that did exist consisted largely of what’s going on in the community type social activity listings columns, with very little substantive or critical coverage of jazz music historically. The most substantive exception would be the column The Jazz Life, written by the iconoclastic pianist-composer turned prolific writer, Herbie Nichols, for the New York Age, an influential black newspaper published from 1887-1960.

Ain’t But a Few of Us includes the insights and perspectives of three such contributors: the distinguished journalist-author Herb Boyd (Amsterdam News), Robin James (Minnesota Spokesman Recorder), and current Amsterdam News writer Ron Scott, likely the current most prolific Black dispatch jazz writer. “As for the bulk of the so-called Black dispatch… if the Michigan Chronicle, the Chicago Defender, and the Pittsburgh Courier are representative of the African American press over the last generation or two, then jazz is virtually nonexistent, and I mean jazz of any style.”

Another exemplar of the so-called Black dispatch is John H. Johnson’s historic, slick monthly Ebony magazine. In her Billie Holiday book, Prof. Griffin details a 1949 cover feature on Holiday that fell squarely in the parlance of “the politics of respectability.” Despite her immense and considerably influential musicality, and her many collaborations with jazz greats and contributions to jazz music, the piece in question is all lifestyle, providing no real sense of Holiday’s musicality or musical pursuits to Ebony’s overwhelmingly Black readership. Instead, as Prof. Griffin recounts, “The article is an explicit bid for black middle-class respectability,” largely bereft of detailing Billie’s pursuits as a signature jazz singer. Such was always the case with Ebony, Jet, Sepia and other Black dispatch magazines; on the rare occasion when a jazz man or woman was covered, it was about lifestyle and middle-class pursuits, as opposed to any sense of music journalism or criticism. They’re more about Miles Davis in the kitchen making bouillabaisse, or on vacation with wife Frances Taylor, than about Miles on the bandstand making music with John Coltrane or Herbie Hancock.

Likewise Bill Brower, who formerly contributed to the weekly Black newspaper the Washington Informer, and has a broad perspective on these matters from his former contributions to the Washington Post (where his byline ended without apparent cause) and as DC correspondent to DownBeat, offers cogent observations from those perspectives in his chapter. “If [jazz] happened in the Black community, the mainstream press wouldn’t cover it – why? Do Black community businesses have the advertising [clout] to advertise in the mainstream press! No, and we know advertising dollars often drive coverage. An [white; mainstream press] editor is going to tell you to go to the Kennedy Center, but they’re not going to send you to cover something a black presenter like [the late] Vernard Gray is producing. Absolutely I think that who the editors are, the beat writers, the columnists are, what they’re comfortable with, who they know, and what they have access to absolutely determines what gets covered… and that’s a problem.”

This book gives voice to the perspectives of two jazz writers I met as young aspiring writers who’ve continued their pursuits, John Murph and Eugene Holley Jr., both of whom I provided access to some of their earliest bylines through the NJSO Journal, the quarterly publication this writer published and edited for the late National Jazz Service Organization. “I didn’t see music journalism as a viable career option because there weren’t that many role models at the magazines, particularly African Americans from my generation,” observes Eugene Holley in Ain’t But a Few of Us. “And writers for say, Rolling Stone, Spin, and Musician magazines seemed galaxies away.”

White editor/publisher restrictions, outright prohibitions, and misinformed senses of privilege are also continuing themes throughout these Ain’t But a Few of Us chapters. From her days as a Billboard magazine columnist, writer Janine Coveney for the first time for publication discussed the white editor privilege she faced at the venerable music trade publication. “Though I was raised in a Caribbean family, and I knew a good bit about reggae, soca, and Latin music and the roots, [editor Timothy] White – who had written the “definitive” Bob Marley biography Catch a Fire, forbad me from ever covering any sort of island music in my column. He literally would take my proofs and scratch out any lines about a reggae release or festival. There was no other place for reggae coverage in the magazine in the 90s, so artists and publicists were counting on me to give them some column inches. I never denied White’s level of expertise on the Marley family legacy, but for him to deny my cultural knowledge was insulting. If there were other motives from him to exclude [my] reggae coverage, he never explained them to me.”

In the April 2003 issue, during his brief stint as a regular columnist for JazzTimes Magazine, Stanley Crouch accused white jazz critics of promoting white musicians over superior black musicians, in order to “make themselves feel more comfortable about evaluating an art form from which they feel substantially alienated.” In response to Crouch’s subsequent firing from his JazzTimes column over such observations, writer Adam Schantz opined: “Whether or not white jazz critics have a race problem, the ones at JazzTimes evidently do. The typical jazz critic is a white man in his 50s who feels underappreciated by the publishing world, a state of affairs he mistakenly blames on jazz’s marginality – or on more prominent critics like Crouch – rather than on the quality of his prose.”

Through our interviews and conversations with Black music writers we explore their respective challenges from those who’ve been magazine & newspaper freelancers, mainstream newspaper correspondents, book authors and academics, jazz periodical editor/publishers, Black dispatch writers, and new media/online contributors. The broadness of Ain’t But a Few of Us explorations of their respective odysseys and challenges readers will find unprecedented, compelling, and quite revealing.