Our recent conversation with DC jazz worker Bill Brower (please scroll down for that dialogue or check the Archives listing for November ’14 entries) was in part an effort at highlighting the often overlooked but very important contributions to keeping the jazz flame lit by good folks who labor beyond the bandstand; namely those culture workers who set the stage and make it possible for jazz artists to ply their craft and enlighten audiences with their artistry. One such culture worker is Todd Barkan. You may remember him from his days operating the now-classic, legendary San Francisco jazz club the Keystone Korner. Others may know him for his travels with the great Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Still others may know him from his more recent curatorial exploits and as your genial host at Dizzy’s Club the spiritual anchor of Jazz at Lincoln Center.

A few weeks back JazzTimes asked me to capture a few recollections of the late, great drummer Idris Muhammad from one of his erstwhile employers, NEA Jazz Master Lou Donaldson. In town for a sold-out concert performance at the Kennedy Center’s jazz-friendly Terrace Theatre, Lou was happy to oblige with some Idris reminiscences that will appear in the upcoming annual JazzTimes obit issue that includes first-person recollections of some of the more notable musicians who’ve passed on to ancestry in the preceding year. Hanging out with Lou backstage that evening was Todd Barkan, who has produced some Lou Donaldson records and works with the great master. Spotting Todd at the Terrace suggested that some questions were in order for one of the most tireless jazz workers in the business.

Todd Barkan with Sonny Rollins

How did you go about developing the Keystone Korner to the point where it achieved legendary status?

By day, I was working full time as a Customs Broker for the venerable San Francisco firm of Hoyt, Shepston & Sciaroni; close to seven nights a week, I also worked as the pianist for the Afro-Cuban jazz band, Kwane & The Kwan-Ditos. On a Monday afternoon in July of 1972, I brought our press kit and cassette tape to the owner of a North Beach blues bar called Keystone Korner, which was next door to a major SF police station. Keystone Korner’s owner, Freddie Herrera, told me that “I don’t really like jazz, and it really doesn’t draw and that audience doesn’t buy any beer,” but then he really surprised me by ingenuously asking “why don’t you just buy this club and hire your own band? I gotta sell this joint ’cause I’m planning on opening a big rock club in Berkeley and I have to come up with a bit more cash to nail down the deal this week.”

I told him that I only had $8,000 to my name that I was saving up for a planned trip to Europe, but he told me to bring my check book back on Wednesday, and he would see what he could do. I came back by in a couple of days with a lawyer buddy, and Mr. Herrera wound up selling me the lease to the club for $12,500, with $5000 down and $400 a month, plus $750 to transfer the beer license over into my name. There I was at the age of 25 as the sole owner of a jazz club, with absolutely no experience in that kind of business except as a musician who played in a lot of bars, army bases, and all kinds of dives all over the Bay Area. To help me get off the ground, Freddy Herrera gave me a couple of free nights with the Jerry Garcia/Merl Saunders Band “because they owe me a couple of favors for canceling recently.”

San Francisco’s Jazz Workshop and Basin Street West had just gone belly up, the Both/And was on its last legs, and the Fillmore West and Rock’n”Roll Scene were flying high in 1972, so everybody thought I was nuts for starting a new jazz club then, but I was just naive, idealistic, and insanely hardworking enough to feel I could make it work. Jerry Garcia had a guy who did nothing but roll joints dipped in hash oil, and the music was ear-splittingly loud, but after that psychedelic swing with Merl Sanders we got a bit more four/four with violinist Michael White with Ray Drummond, Kenneth Nash, and Ed Kelly, and then Bobby Hutcherson with George Cables, Herbie Lewis, and

Billy Higgins. I brought in McCoy Tyner‘s Quartet from New York with Sonny Fortune, Calvin Hill, and Alphonse Mouzon, for two weeks, and we were off to the races!

In order to set up the gig with McCoy Tyner, I got Jimmy Lyons to book Tyner’s band at the Monterey Jazz Festival before our Keystone gig, and we took 10,000 McCoy At The Keystone flyers down to the Festival and plastered every set of windshield wipers and storefronts in that whole town to help put our hippy jazz club on the map, and we kept doing that kind of street poster guerrilla marketing for Keystone Korner for the next eleven years all over the greater San Francisco Bay Area with a whole network of jazz volunteers.

Make no mistake about it: Keystone Korner was above and beyond anything else a total labor of love in every possible way. All the folks who worked there were either musicians or passionate jazz maniacs; even the janitor was a bebopper. We had psychedelic murals on all the inner and outer walls, and air purifiers (ionizers) to take the pot and cigarette smoke out of the air for the comfort of the patrons who did not smoke. Most of us worked seven days and nights a week, 52 weeks a year. When we simply paid the rent, the phone bill, the state sales tax, and all the band fees, it was a cause of real and sincere celebration.

When Miles Davis played one of several gigs he did at the Keystone in 1975, we paid him the astronomical fee (for us) of $12,500 for the week (all in cash of course) by Saturday night of the six-night engagement. On Sunday night, Miles’ road manager and percussionist, Mtume, brought me back one envelope with $2500 in it because, as Mtume explained, “We just played in Japan, so we’re okay, but Miles thinks you need this money at this point much more than he does.” Miles was right, and that certainly helped to pay the bills. That is the kind of place it was.

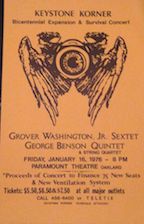

All ages were welcome because we had two very successful benefit concerts for the Keystone at the 3500-hundred-seat Paramount Theatre in Oakland early on in our eleven-year-run: first, the Black Classical Music Society with Freddie Hubbard, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, McCoy Tyner, Ron Carter, and Elvin Jones raised over $80,000 to help buy a hard liquor license in February of 1975, and then the bands of George Benson (with a string Quartet) and Grover Washington, Jr., teamed up to generate the revenue for a full kitchen to enable us to serve minors.

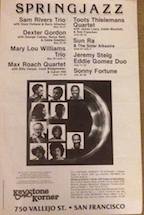

Starting with Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s historic recording “Bright Moments,” Keystone Korner’s international reputation as a consistently warm and welcoming home for the music was greatly enhanced and accelerated by countless high quality live recordings by the likes of Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, Tete Montoliu, McCoy Tyner, Yusef Lateef, Stan Getz, Freddie Hubbard, Zoot Sims, Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Henderson, Cedar Walton, Dexter Gordon, Woody Shaw, and Bill Evans, and regular New Year’s Eve broadcasts by National Public Radio really helped to spread the word as well.

L to R: Dexter Gordon, Max Roach, Todd Barkan, Bobby Hutcherson, Eddie Henderson – Keystone Korner salad days

When the Keystone Korner closed how was shifting your focus to New York the obvious move?

The Keystone Korner closed in 1983 because we could not afford to renew the lease, but that was the year that Randall Kline and SFJAZZ were just starting to present concerts in the Bay Area, and Yoshi’s in Oakland was also just beginning to be a very important keeper of the flame. My longtime friend and colleague Michael Cuscuna provided invaluable assistance for my move that year to the Jazz Capital of the World, where I started managing the Boys Choir of Harlem and producing several hundred jazz recordings in New York City for both Japanese and American record companies, especially Fantasy/Prestige/Milestone Records. Because so many centrally important people in the jazz world live and work regularly in New York, I felt I was coming “back home” when I moved to NYC over thirty years ago, even though I had grown up in Columbus, Ohio, where I was blessed to have Rahsaan Roland Kirk as a mentor, and I worked on my first jazz concerts at Oberlin College, in Oberlin, Ohio, before I drove out to San Francisco in a 1941 Cadillac looking for Paladin during the Summer of Love in 1967.

What have been some of your biggest successes since you got to NYC?

While I was serving as the Manager of the Boys Choir of Harlem from 1985-1990, I really enjoyed helping to start up and build their international touring program and working on very memorable recordings with Dr. Walter J. Turnbull and the Choir with Kathleen Battle, Kenny Burrell, Billy Taylor, Grady Tate, and the St. Luke’s Orchestra. On my wall at home is a little wood’n’brass plaque that means more to me than almost any other recognition (far more than any Grammy or Japanese Gold Disc from Swing Journal) I’ve received in the 50+ years that I’ve worked with our music. It reads “The Boys Choir of Harlem Parents Association 2nd Annual Merit Award presented to Todd C. Barkan in recognition for your outstanding service to the boys and girls of the Boys Choir of Harlem, Inc. February 26, 1989.” I am so proud of the fact almost all our kids graduated from high school, and most of them went to college.

I’m also very proud of having served as an Artistic Administrator at Jazz at Lincoln Center and the Programming Director of Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola at JALC from 2001 to 2012. When Wynton Marsalis first started working with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers in 1981, I introduced him to the President of Columbia Jazz Records, Dr. George Butler, in my office at Keystone Korner in San Francisco. I was very honored and happy when Wynton called upon me in 2000 to work at JALC and to prepare to be a central engine to get Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola off the ground and to help build it into one of the premier international jazz venues in the world. Serving Jazz at Lincoln Center in innumerable ways for twelve years was one of the most satisfying experiences of my life in music.

Todd Barkan and Gerald Wilson onstage at Dizzy’s

Equally satisfying have been the wonderful opportunity and privilege to work extensively on both recordings and touring with very special creative artists and friends like Chico O’Farrill, Bebo Valdes, Grover Washington, Jr., Jerry Gonzalez & The Fort Apache Band, and Freddy Cole, and the blessing to program the Keystone Korner Tokyo in the early 1990s.

On the recording side you’ve done a lot of producing. More recently at least part of your efforts have been to unearth sessions recorded live at the Keystone Korner for release. Were those simply happy circumstances or at the time you were running the club did you have eyes to make a series of recordings made live at the club? And what was it about that club that made it a good recording environment? Will there be more recordings caught live at the Keystone Korner?

Between 1972-1983, there were quite a few commercial live recording sessions at Keystone Korner by Rahsaan Roland Kirk & The Vibration Society, McCoy Tyner Quintet, Yusef Lateef Quartet with Kenny Barron, Bob Cunningham, and Tootie Heath, Tete Montoliu Trio with Herbie Lewis and Billy Higgins, Sonny Stitt with Cedar Walton, Freddie Hubbard with Bobby Hutcherson and Joe Henderson, Stan Getz Quartet, Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers with Wynton Marsalis and Bobby Watson, and Paquito D’Rivera Quintet, but all the rest of the live recordings released from the club were simply archival recordings (mostly cassettes). Some of my favorites are the final 16 cds by the Bill Evans Trio with Marc Johnson and Joe LaBarbera; All The Way Live, the only time Eddie Harris and Jimmy Smith ever recorded together; and The Magic of Two, extraordinary piano duets by Tommy Flanagan and Jaki Byard. There will be a lot more very special live recordings released with great care in the years to come.

Since you left Dizzy’s, what’s been the focus of your activities?

Since I left Jazz at Lincoln Center two years ago, I have been working a lot on a book of memoirs about my first 50 years of being lucky enough to make the world a little more safe for bebop. In 2103, I produced another one hundred nights of live jazz presentations in New York City, at both the IRIDIUM JAZZ CLUB (” KEYSTONE KORNER PRESENTS”) and 54 BELOW (“THE WBGO JAZZ SERIES”).

In 2014, I was thrilled to be hired as Programming Director for the Creative City Collaborative and Arts Garage in Delray Beach and Pompano Beach, Florida, and for the last five years I have really enjoyed working for THE JAZZ CRUISE 2011-2015 which originates in Fort Lauderdale. I give a jazz video lecture each morning on the Cruise besides programming two on-board television channels with 24-hours-a-day for 7 days of the best jazz videos I know in the world, as well as emceeing a couple of dozen concerts at sea.

As one who has so often ‘set the stage’, what in your estimation have been some of the most important developments in presenting jazz since your Keystone Korner days?

I think one of the greatest, and ever-increasing challenges to presenting this music and perpetuating this awesome legacy to try to help it grow ever stronger is to provide as many live and loving venues for the music to be created and nurtured in. In an evermore sensorily-bombarded, ADDS world overwhelmed with so much indiscriminate mediocrity, it is much harder than ever for true quality to break through and find a substantial audience, which just means we must persevere and be more creative and resourceful than ever in how we get the best art out there.

While I was at Dizzy’s Club, I strove very, very consistently to substantially help great young artists such as Cyrille Aimee, Elio Villafranca, Brianna Thomas, Edmar Castaneda, Christian Sands, Sharel Cassity, Cecile McLorin Salvant, Aaron Diehl, Ulysses Owens, Jr.and others. They are an important part of the real future of our music. Take care of the music, and the music will take care of all of us.

One Response to Keeping the flame alive with Todd Barkan