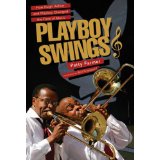

There is no more relaxing activity than laying out under the sun with the inviting surf mere feet away, absolutely chilling with a good book. Just in time for family beach week, arrived an informative, page-turning new read on the legacy of Playboy magazine’s once expansive enterprises and its rich music legacy. Playboy Swings (pub: Beaufort Books), by Patty Farmer with jazz vocal specialist Will Friedwald, is ostensibly about the considerable contributions of Hugh Hefner and his Playboy enterprises to the music scene, with robust coverage of Playboy’s important stake in jazz. Though the book provides many fine details on how Hefner and his cohorts love of specifically jazz morphed into the former Playboy Magazine Jazz Polls (including some resulting “all-star” recording sessions and a less-than-successful record company venture), the now-annual Playboy Jazz Festival, and the once far-flung Playboy Clubs, this is not purely about jazz… or music. Some of this book’s finest revelations and insights are about the vast booking and presenting policy of the Playboy Club chain, not only as it pertains to musicians (with an emphasis on singers), but also numerous insights and revelations about the role and work of comedians and what might best be dubbed variety entertainers on the Playboy Club circuit. Playboy Swings also offers a definitive insider look at the development and execution of Hefner’s two television shows – Playboy’s Penthouse and Playboy After Dark, each of which had a kind of hang-fly, informal quality that was trailblazing in their own right. Not least of Hefner’s efforts was his dismissal of the color barrier that plagued much of 20th century America (still does). He willfully provided platforms for many African American performers of the day, clearly a well-earned arrow in his quiver.

Apropos one of the book’s forwards is contributed by NEA Jazz Master George Wein, the dean of jazz festival presenters. As ongoing producer – via one of his ace right hands Darlene Chan – of the annual Hollywood Bowl weekend known as the Playboy Jazz Festival, the signature such event in Southern California, Wein was right there when Hefner determined to present this keynote event annually. But first came an extravaganza that the late critic Leonard Feather once dubbed the “greatest three days in the history of jazz” – the original Playboy Jazz Festival. Each of these enterprises is balanced by the prevailing social mores of their day, mores which often found certain parts of the country looking askance at Playboy’s unique juggling act balancing its high class skin mag proclivities, including its loosey-goosey promotion of a supposed “playboy lifestyle”, with its promotion and presentation of some of the finest music and comic artists of primarily the 50s, 60s, and 70s.

Ms. Farmer paints a fascinatingly detailed portrait of the first-ever Playboy Jazz Festival. Held in the magazine’s original headquarters city of Chicago, Hefner & company’s first festival faced down several obstacles, in addition to the ongoing theme of certain conservative perceptions of the parent magazine. The odyssey of its chosen venue is detailed, ranging from Hef and company’s original intent to present at Soldier Field, which was shot down by the looming specter of the Third Pan-American Games, to be staged later that summer at that very stadium. Eventually the event landed at what was then known as the old Chicago Stadium, the city’s indoor basketball and hockey palace. The event ran the weekend of August 7, 1959 featuring a virtual who’s who of the music: Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Oscar Peterson, Coleman Hawkins, Jack Teagarden, Sonny Rollins, Pee Wee Russell and a host of others. One funny anecdote about that festival concerns Frank Sinatra.d

Seems the Chairman was too busy in Hollywood at the time to play the festival, though history has many of the fans believing they’d actually seen Sinatra perform among the incredible array of talent. One thing led to another and a Sinatra impersonator was casually dropped into the middle of the festival, strolled onstage and sang “Come Fly With Me” with the Basie band, to wild response! The emcee for that day was the comic Mort Sahl, who informed the author that “…the crowd went crazy cheering” for what they thought was Sinatra. “They booed me when I took the mic and let them know it wasn’t Sinatra they’d just heard!” Despite Sahl’s disclaimer, many left the stadium that day glowing from what they thought was a Sinatra sighting. This book is loaded with such rich anecdotes and remembrances.

Later in the book, during the extensive and finely detailed chapters on the development of what became a vast network of Playboy Clubs literally across the globe, Farmer details a hilarious scat singing jam between Jon Hendricks and Sammy Davis, Jr., who’d dropped by the London club after finishing his evening performance of Golden Boy. “He challenged me to a scat exchange. And of course, I accepted!,” said Hendricks. “He gave me a trip du challenge!”

Equally fascinating is Farmer’s detailed chronicle of how, ironically given the company’s male-centric composition built on its highly successful magazine platform, one woman who’d been featured in a Playboy pictorial in October 1970, became a key Playboy Club performer and actually took over management of the L.A. Playboy Club at a time when much of the Club enterprise had begun floundering with the changing entertainment mores in America. The story of singer-actress Lainie Kazan‘s Playboy Club trajectory is textbook stuff in a sort of serendipitous marriage of talent and enterprise, much of it larded with good jazz.

Subtitled “How Hugh Hefner and Playboy changed the face of Music” this book certainly has the goods to back up that lofty contention. And through it all Hefner remains a steadfast jazz enthusiast who frequently put his money where his artistic interests lay. On the clubs, development of which are detailed in this book from soup to nuts, this passage is particularly definitive:

The Playboy Clubs were at the center of an iconic period of our cultural history and they helped define it as a carefree, liberated time when boundaries were pushed – and sometimes broken. Over nearly three decades, the impact of the clubs on musical taste and entertainment standards is undeniable. They provided a home, a school, and a livelihood for a multitude of musicians, singers, comics, and restaurant personnel – all the while helping to topple the color barrier in entertainment. You could say that they trained a generation of audiences from around the world to appreciate good music, good food, and good company.”

One Response to Playboy & the Music