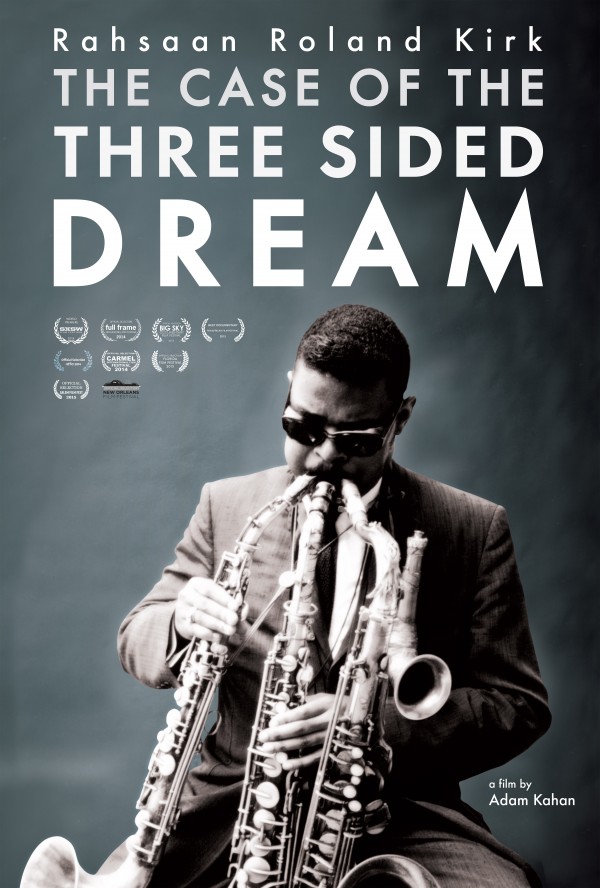

Rahsaan Roland Kirk is one of the most singular, thoroughly unique musicians – and characters – in the annals of 20th century music. His story stands in vivid relief as one of triumph over tragedy, laced with enormous wells of humor and pathos. Filmmaker Adam Kahan has produced a remarkable documentary on Kirk, “The Case of the Three-Sided Dream” and I was fortunate to catch a screening last spring during the DC Film Festival. “The Case of the Three-Sided Dream” is slated to be released on May 31, and I’ll let Adam tell you more about that and his motivation for chronicling this one-of-a-kind figure.

We are about to make the film available commercially through Vimeo on Demand (streaming and download, May 1), itunes (streaming and download, May 31) and on DVD through Amazon in the fall. If you can mention that, that would be great. Here is a link to Vimeo-

What motivated you to produce a documentary on Rahsaan Roland Kirk?

First and foremost, Rahsaan spoke to me on an emotional level.

I knew nothing about jazz (liked music, but had a pretty limited view – weaned on classic rock, moved on to punk rock, didn’t know much more). I knew I wanted to get into jazz, so I decided to pick up a few records at a garage sale (this was in San Francisco, 1989). I picked up a Louis Armstrong record, one by Count Basie, and The Best of Rahsaan Roland Kirk on Atlantic records. The record just had a head shot of him on the cover, no visuals cuing the three horns or anything else. I was in for a surprise… I still don’t think I’ve listened to those other two records… I ended up playing that Rahsaan record until the needle wore out the grooves. I had just broken up with my girlfriend, had moved out, and was living alone in a dismal apartment on the bad side of town. I just kept playing that record, and I remember specifically – Lady’s Blues, which was a Rahsaan with strings arrangement, with him on the flute. In a way, he got me through a rough time. And I was hooked.

His music is so emotional, really comes from the guts and hits you in that same place. Then on top of that, he has this super-human, virtuosic ability as a player. Then, on top of that – when I started reading about his life story, and all the obstacles he faced, and overcame, well that’s when I decided to make the film. He is so rich on so many levels – musically, visually, life story… Just so far beyond. A film on Rahsaan seemed not only like a no-brainer, but a MUST.

I am still trying to get enough momentum up to do a bio-pic on Rahsaan and do have a script (my momentum isn’t the problem actually, it is the need for an executive producer and $$). That is a conversation I’d still like to have with someone… As I am sure you know, his story is just so rich, there is so much material there. It’s a field day for a filmmaker/writer/producer.

How long did it take for this documentary project to be completed?

This project took a long time… It’s a little tricky to say. I actually started in 1999 when I moved back to New York form France. I was talking about Rahsaan to my friend Reed Anderson, and saying how someone should make a film on him, and then my friend says – YOU should make a film on him. So I opened a phone book (remember those?!) and found the phone number for Joel Dorn -the legendary Atlantic Records producer and Rahsaan’s partner in crime for so many years. (Joel’s liner notes were also a huge inspiration for me to do this film.) Joel was a great guy and very open and into the project. We did some interviews. He introduced me to Dorthaan. He introduced me to Steve Turre. John Kruth was just finishing his book on Rahsaan at the time and he was gracious enough to share all of his Rahsaan contacts with me, so I got to Ron Burton, Walter Perkins, Hilton Ruiz, and then even [first wife] Edith Kirk and of course [son] Rory Kirk, and so many more. It took me about 5 years to get a pretty much finished version of the film done. But then it just sat on the shelf, largely because I could not get funding to license all of the music and archival material. Years passed (8 to be precise) and I picked it back up in 2012 and decided I had to push it through to finish. But after all that time, the old interviews looked really dated and the production quality was not good at all. They were really unacceptable from a visual quality standpoint, and I think that is why the film in its original version did not gain enough traction. So I decided to remake the film entirely. I re-shot all the interviews, but the problem was – some of the people had passed away, notably – Joel Dorn, Edith Kirk, Hilton Ruiz, Trudy Pitts, Frank Foster Walter Perkins and Bruce Woody. So these people are not in the film! It was a tough choice, but again, I felt (and still feel) that the film was not being taken seriously because of the low-quality of these interviews, so I had to take them out. I re-shot with all who were still around (Dorthaan, Rory, Steve Turre, Ron Burton…) and the film started to have “legs” as they say. I finished it in 2014. It took me two years to remake it (of course then I knew exactly what the story was, what clips I wanted to use, etc.) I should also mention that we will include Joel in the DVD extras.

What was your process for putting this film together, from start to finish?

It really started with finding and engaging all of the people from Rahsaan’s world, starting with Joel and then all of the others. Simultaneously I had to unearth the archival footage of him. Now, on the internet, it is pretty easy to find stuff. But when I started (again – ’99), it wasn’t so easy. So every new piece of footage was a jewel. I also found some stuff that is still not on the internet and I don’t think will ever be – it’s only in my film! Some really rare stuff like – well for one – home movies that Dorthaan Kirk gave me, also a post-stroke performance on Ken Kesey’s farm in 1977, and the biggie – his performance on the Ed Sullivan show with an all star band… (you’ll have to see the film to find out who… though I can tell you – one of the guys in the clip starts with a Charles and ends with a Mingus… but there are other giants with him on that date too…) Then it became about putting the puzzle together. Also, I had some audio recordings of Rahsaan talking on stage I wanted to use (because his stage persona was such a big part of what he did). But I didn’t know what to do for these segments for video, for what we would actually see in the film while we hear Rahsaan talking. The obvious would have been (like most documentaries) to do some slow pans into still pictures of Rahsaan, a la Ken Burns, or every other filmmaker. But because Rahsaan was anything but obvious, because he would never do the conventional, or what is expected, or what was easy, I wanted the film to take the same approach. So panning in to photos was out of the question. After much thought and many unsuccessful ideas/tries, I found a great animator/artist, (named Mans Swanberg) who really “got” Rahsaan. So we have these wonderful cosmic animated passages in the film that he created (one reviewer describes them as Fat Albert meets Yellow Submarine…) The rest was a lot of editing, massaging… Above all – I wanted to show Rahsaan in the film. So we include long passages of music and of him talking. After all, he is the star of the show.

What new facets did you discover about Rahsaan as you were researching for this project?

I read a lot about Rahsaan. All the liner notes, the book by John Kruth, another book by a French writer named Guy Cosson, and… there is a guy name George Bonifacio… Joel Dorn connected me to him in the early goings. George is the self-appointed (I believe) archivist for an ambitious collection of Rahsaan stuff, so to speak – newspaper clippings, dates, photos, recordings… He has a dense pile of articles on Rahsaan that he made available to me. There are so many great stories about Rahsaan that I discovered, and just could not get in the film unfortunately. Things like – Rahsaan driving a car (yes he was blind and drove a car), getting arrested for hijacking a plane (no he didn’t do that, but was arrested as a suspect because someone thought he as going to), Rahsaan breathing under water, and through his ears, his anger and outrage about the way the musicians and his music (Jazz, what he called – Black Classical Music) were treated in this country. So many things… the practical joker side of him (he had one of those hand buzzers that would shock you when you shook hands with him), and all the deep and sincere love that his fellow musicians, family and friends had for him. They really loved him. After making this film, I also realized that, at the very core of his being, this man was a pure Blues musician.

Given what you learned about him throughout this process, did your perception of Rahsaan Roland Kirk and his impact change at all from start to finish?

My perception grew deeper, because Rahsaan was so very deep. And my appreciation grew deeper. Impact is a tough one. He definitely had an impact on what Joel Dorn called “a small core of lunatics”, but I still think he is largely under appreciated, and not known nearly as widely as he really should be. Knowledge of him and his legacy is always growing. Is it enough? I don’t think so. I still think he has not gotten his “just due” so to speak. Most or all of the people in the film agree. His friend Mark Davis told me – “part of my image of fairness in the world, was that Rahsaan was going to get the recognition he so deserved… [and when that did not happen]… it was a message that – life sucks and it doesn’t matter what you do, who you are…” Mark is not necessarily a pessimistic guy, he is in fact a beautiful human being, but he, like most of the people from the Rahsaan world, and certainly Rahsaan himself, were really perplexed and deeply bothered by the fact that Rahsaan did not achieve wider acclaim. Someone once mentioned Rahsaan and Buddy Rich to Edith Kirk in the same breath, and she responded – “Oh Buddy Rich, we can beat him any day!” I think she was right! And then I think of all the recognition for some of the jazz giants like Miles, Trane, Monk, Duke Ellington… these guys are “A list” jazzers for sure. And their names are widely known outside of jazz. Yes – they deserve to be at the top of the pile by all means, but most of us (and now I’m talking about those in the Rahsaan world, the small core of lunatics who Joel also described as “a box of broken cookies”), we feel that Rahsaan should be there too. And he is not.

Ultimately what impressions are you striving to convey to those who experience The Case of the Three-Sided Dream?

This is a guy not to be missed. Don’t fall asleep on this guy. He is a beautiful, spiritual, unique individual with a one of a kind legacy. He is someone you want to check out.