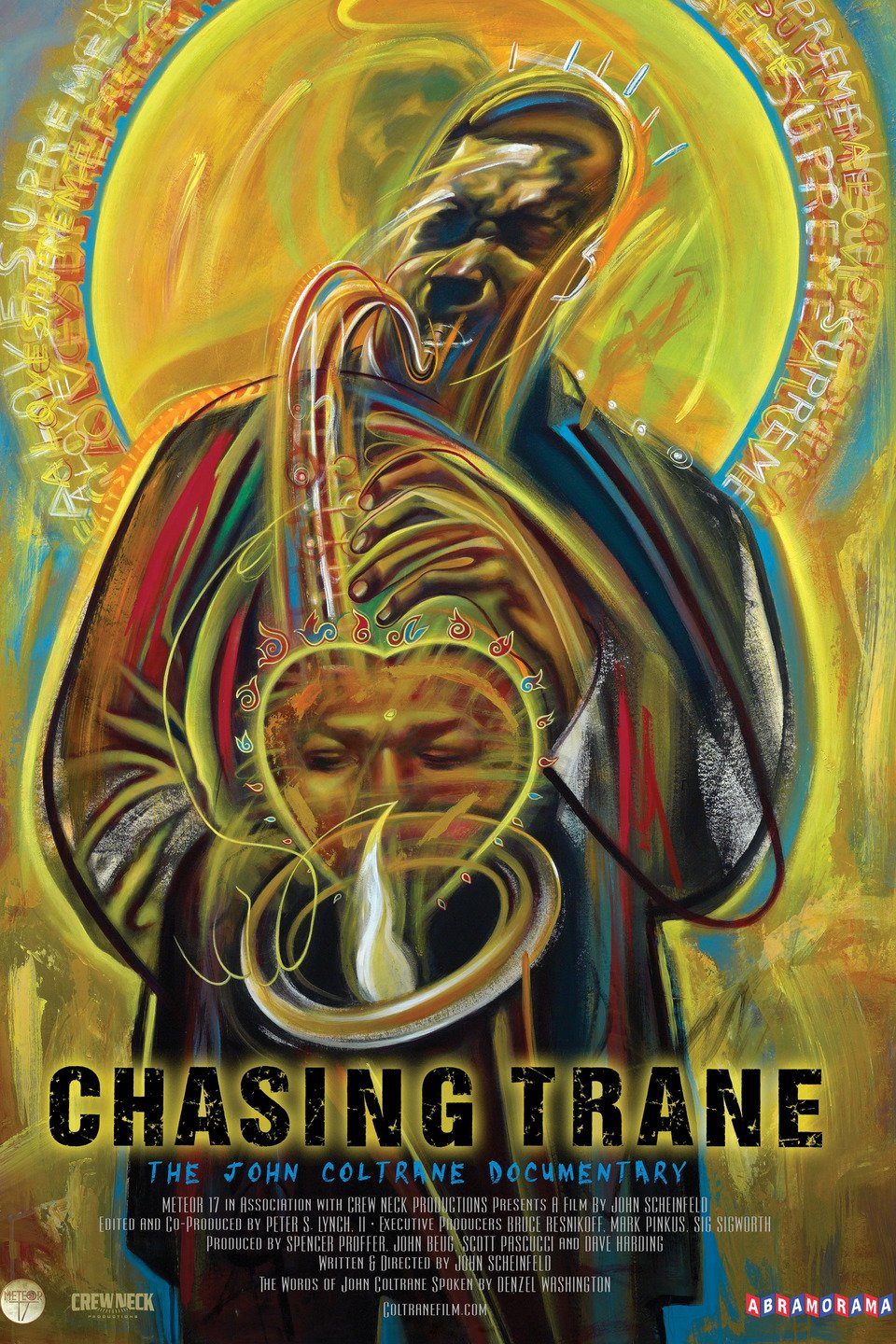

This must be the season for deeply penetrating jazz documentary films! In the midst of much – and well-deserved – positive buzz about the current Lee Morgan doc “I Called Him Morgan” comes the John Coltrane documentary “Chasing Trane”. Last weekend I had the pleasure of serving on a post-screening panel discussion following a “Chasing Trane” screening at the annual Annapolis Film Festival. For much of the audience that packed the house that evening, “Chasing Trane” was a real revelation, offering an in-depth look at a man many in the audience knew of as a jazz legend… but not much more.

The film follows Trane’s humble North Carolina family roots north to Philadelphia. The telling of his family bio offered such keen insights as the fact that both of John Coltrane’s grandfathers were preachers, which in at least one of the film’s testaments from the exceptional legion of intimates, scholars, writers and enthusiasts who offered their take on Trane’s impact, indelibly influenced the storytelling inflection and cadence of the man’s horns.

Filmmaker John Scheinfeld assembled a prodigious cast of talking heads to testify to John Coltrane’s greatness from several angles, including sons Ravi and Oran Coltrane, and his stepdaughter (daughter of first wife Naima; for whom Trane dedicated his piece “Sayeeda’s Song Flute”); musical intimates Sonny Rollins, Philly homeboys Jimmy Heath and Benny Golson, and acolytes Wynton Marsalis and Kamasi Washington; such writer-critics and historians as Ashley Khan (another who sat on that Annapolis panel), Ben Ratliff and Lewis Porter; Coltrane enthusiasts from across the imaginary musical divide as Carlos Santana, Common and Doors drummer John Densmore; and such socio-political figures as Bill Clinton and Cornel West. With such a broad cast of dialogue contributors, one might get lost in identifying each cogent bit of testimony; thankfully Scheinfeld cannily employed the introductory graphic each time this crew was called upon to offer their take on Trane’s arc, which may seem an insignificant touch but proved quite effective in enabling viewers to keep up with the source of such insights.

Apparently not enough useful footage exists of John Coltrane’s voice to include in this film (though one wonders whether they checked Frank Kofsky’s Coltrane interview from the Pacifica Radio Archives), so the actual words of John Coltrane were effectively narrated by actor Denzel Washington. Hearing Denzel express Trane’s words took this viewer back to the potent sequence in Spike Lee’s jazz film Mo’ Better Blues where Washington’s character rehabs his assault & battery ruined trumpet chops to a recording of Coltrane’s powerful spiritual gemstone “Tunji”.

John Coltrane’s career is detailed from his days as a road warrior and sometime bar walker on the chitlin’ circuit as an itinerant section tenor, to his time in Dizzy Gillespie‘s bop orchestra, to his early development as a recording artist, and his signature moments with Miles Davis quintet and sextet. That Trane succumbed to hard drugs was not surprising given the times he came up in, and how he triumphed over his habit is given new detail, including particularly poignant testimony from his stepdaughter on his cold turkey battle at home with the twin demons of heroin and alcohol abuse.

Among the more warmly revealing elements of “Chasing Trane” are the frequent glimpses of John Coltrane the family man. His life with Naima is explored in greater detail than previously known, expressed most lovingly by his stepdaughter. John meeting and courting his second wife, pianist Alice McLeod, is beautifully detailed, as is their married life together. Included are lovely still photographs of John Coltrane the family man, including family life in the home they shared in Dix Hills on Long Island.

We tend to think of John Coltrane in terms usually reserved for deities, but “Chasing Trane” provides a more nuanced sense the humanity of John Coltrane. There are several sequences of home family movies included in the film, including shots of an everyday John Coltrane enjoying his family, playing in the backyard with his dog, even a sequence of him taking a road trip respite at the side of some turnpike with Alice and one of their children. This film does much to humanize John Coltrane the man.

Each of John Coltrane’s musical touchstones are explored in this film, from the influence of Charlie Parker (the erudite Benny Golson recalling the impact of Bird when the two of them first saw Parker on the bandstand in Philly), to his Dizzy Gillespie tenure, to his early days as a recording artist, to his two Miles Davis band stints (the first sequence ending with Davis firing a drug-addled Coltrane, the second introducing a drug-free Coltrane invited back into the band and including Davis’ “Kind of Blue” monument). The passage detailing his hit recording of “My Favorite Things” elicited a moment of knowing recognition from the Annapolis screening audience as they recognized that familiar melody. Trane’s enduring classic spiritual high point, “A Love Supreme,” is explored in rich detail from his home sequestration as he developed that deep meditation, as is his assembly of the classic quartet of McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones, and Jimmy Garrison who helped deliver that classic.

The impact of the final Coltrane working unit of Alice Coltrane on piano, Rashid Ali on drums, Pharaoh Sanders on second tenor, and holdover Jimmy Garrison on bass, which ushered in the freest of John’s music, was to some a bit unsettling. In the film Cornel West throws up his figurative hands at this period of Coltrane’s artistry, respecting Trane’s intentions but admitting lack of true understanding or appreciation for this late period Coltrane.

Another of the film’s laudatory sequences occurs as Coltrane is struggling with the liver cancer that took him out (with testimony from intimates about his noticeable health decline and the fact that he was often seen holding his side in pain, which is illustrated by a still photo of Trane doing just that), but not before a grueling but ultimately rewarding final tour of Japan. In Japan we see Trane praying before a Nagasaki memorial to victims of the devastating A-bomb, in part a testament from a Japanese survivor of that horror who ironically assisted and accompanied the band on their final tour, as well as somewhat humorous commentary from a Coltrane obsessive who amassed so much Trane memorabilia he needed a separate building to house it all!

Ultimately both “Chasing Trane” and “I Called Him Morgan” should receive serious consideration when the next film awards season rolls around. Kudos to the Annapolis Film Festival for bringing “Chasing Trane” to its audience. For those of you in the DC area “Chasing Trane” will screen April 28-May 4 at the E Street Cinema. For a schedule of U.S. screenings and additional information on “Chasing Trane” visit www.coltranefilm.com.

3 Responses to Chasing Trane