Q-Tip forged a productive partnership with Jason Moran in the debut of the Kennedy Center’s hip hop program [Photo: Kyle Gustafson/WP]

The current era of jazz musician-as-curator is arguably owed to Wynton Marsalis‘ remarkable success in establishing and building the Jazz at Lincoln Center institution. Examples include the SFJazz organization’s successful engagement of a rotating cast of curating musicians. Trumpeter Dave Douglas founded and curates the annual fall Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT). Yet another trumpeter, Sean Jones, was recently appointed as an artistic adviser to Carnegie Hall, principally guiding their youth jazz orchestra project NYO, which comes with implications for Jones as curator. An auspicious fine arts crossover found bassist-composer-vocalist Esperanza Spalding recently curating the “Esperanza Spalding Selects” visual arts exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in Manhattan, an exhibit that will be on display through early 2018. Doubtless bassist William Parker‘s network of connections has played some curatorial measure at the annual Vision Festival, which is run principally by his earnest dancer-choreographer spouse Patricia Nicholson Parker. And as reported in a recent post in these pages, bassist Christian McBride, artistic director of the Newport Jazz Festival, even had festival founder – and the father of jazz festivals in this country – NEA Jazz Master George Wein motoring around the grounds marveling at hearing artists he’d not previously experienced in McBride’s first full-blown NJF curation.

The Kennedy Center built its laudatory jazz program on the curatorial gifts of Dr. Billy Taylor, the foundation being a series of concerts where the good doctor’s trio played host to a series of guest artists for performances and Taylor’s graceful and deeply informative meet the artist interview component, a series captured for posterity by NPR. Considering Mr. Taylor’s senior status keen observers had to wonder what would happen with Kennedy Center Jazz when he inevitably succumbed to the vicissitudes of age. Thus when the beloved Billy passed on to ancestry in 2010, those of us who followed the program wondered aloud ‘what now’?

The answer arrived in November 2011 when Kennedy Center Jazz chief administrator Kevin Struthers and the institution selected pianist-composer Jason Moran as artistic adviser to succeed and expand on Billy Taylor’s vision. Throughout his career up to that point the Houston-bred Moran had shown an impressive depth of ideas with a balanced inside/outside perspective – from sampling a Turkish telephone call to improvising on an inspiring speech as found objects for composition, to assembling one of the signature trios in American music, the Bandwagon with drummer Nasheet Waits and bassist Taurus Mateen, and challenging the band with fresh landscapes with every recording, to the record label Yes he is developing with wife Alicia Hall Moran, herself an impressive contralto vocalist.

Since building his Kennedy Center program Moran has significantly broadened the Kennedy Center’s definition of jazz, from engaging senior warriors identified with the so-called jazz avant garde who’d not previously played the KC, like NEA Jazz Masters Muhal Richard Abrams and Anthony Braxton in concert (a Cecil Taylor booking was waylaid by illness), to presenting series of next gen jazz contributors at the KC Jazz Club, to Concert Hall intersections with artists in dance and classical music, to a recent triumph with the KC-resident National Symphony Orchestra for a live recreation of Moran’s score for Ava Duvernay’s much-acclaimed film Selma. Viewing the film for a second time, in a big hall with 2K in the seats, Jason & the orch onstage, was a rich experience. No two programs better illustrated Jason Moran’s range than last week’s Friday/Monday sequence which found Moran inhabiting freestyle hip hop and the Thelonious Monk Centennial in succession.

In addition to his jazz program curating, Moran has obviously become quite the artistic force across genres at the KC. Hip hop auteur Q-Tip, best known for his frontman work with A Tribe Called Quest, which established it’s jazz influences early on with their notable second album collaboration with NEA Jazz Master bassist Ron Carter on “The Low End Theory,” credits Moran for his appointment as the new artistic director for hip-hop culture at the Kennedy Center; thus the KC becomes the first major fine arts center to adapt hip hop as a core program. October 6th marked the official launch of the KC’s hip hop program and it was a special night from several perspectives.

That inaugural program coupled Moran and Q-Tip in duo, a format which likely raised questions in Tip’s legion of followers, but they packed the house nonetheless. Significantly the venue, the redesigned Terrace Theatre on the KC’s penthouse level, which had long served as the primary home of the jazz program, was also being launched following months of reconstructive surgery. In her introductory remarks, KC President Deborah Rutter, whose grasp and warm embrace of the complete thrust and responsibility of the Kennedy Center to reflect a broad sense of the diversity of fine arts presenting has been impressive since her 2014 appointment, enthusiastically lauded the Terrace re-design and was obviously thrilled in anticipation of this launch of the hip hop program, whose administrator is Simone Eccelston.

Appropriately though the entire thrust of the program clearly illustrated true partnership, Q-Tip delivered an opening solo sequence that completely enlivened the full house, most of whom had obviously come for his artistry first & foremost. His DJ set displayed impressive dexterity on the wheels of steel and various sampling and looping effects owed largely to popular dance grooves, which by turns he verbally cued as disco breaks. The crowd, though a more mature house that one might encounter at the club, took a minute to warm up but once they did it was definitely on, Tip eliciting amens with familiar refrains & beats. Q-Tip cannily and warmly recognized the significance of hip-hop’s evolution from street parties and basement jams to fine arts center in his accompanying dialogue, citing pioneer Bronx scenesters of the form as DJs Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash, and Afrika Baambaata in his running monologue.

When Moran arrived onstage almost immediately the scene shifted to beats meets virtuosity as Q-Tip crafted his beats to undergird and challenge Moran’s pianistics. This landscape was best exploited when Moran launched into a cosmo-electro-acoustic update on John Coltrane‘s “Giant Steps.” Taking the mic Moran made it clear to Q-Tip’s audience that he was no tourist, telling them that while his generation was addressing the challenges of Thelonious Monk, they were also by equal turns taking on A Tribe Called Quest as artistic sustenance, tacitly informing the audience that his was the first generation of jazz musicians to grow up under the influence of hip hop’s nascent developments & full flowering as a global artistic force, and embrace the form as one of the informers of their jazz expressions.

While there were some in the crowd – particularly those for whom Jason Moran was a new flavor – who were a bit quizzical about the hang-fly nature of this kinetic duo, those who gave themselves over to the impromptu nature (though at certain points it was clear Moran had some pre-planned sketches at his disposal) of this program were duly rewarded by their openness. After their first segment, Q-Tip exclaimed in genuine wonder that they had just free-formed for “about an hour!”

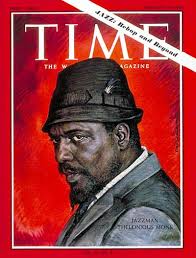

Two nights later Moran amply displayed the breadth of his musical mindset in black suit and bowtie for the Thelonious Monk Centennial celebration in the KC Concert Hall. When the lights dimmed the sound serenading the audience was Monk himself, piano soloing his signature “Round Midnight.” From there Moran essayed the master’s “Bemsha Swing” and introduced NEA Jazz Master pianist Kenny Barron for some solo “Light Blue”. The two pianists played alternating solo Monk before WPFW jazz programmer Brother Ah – who as his given name Robert Northern had contributed his french horn stylings to Thelonious’ historic Town Hall orchestral concert – eased out to reminisce a bit about a great memory of Monk wheeling his old upright onto a Bronx playground to practice. Moran’s idea for the Brother Ah playground reminiscence was spurred by his impression of a museum piece of an urban playground scene, which served to further highlight another constant character on this superb evening a running video installation. The first half closer was a brilliant, slightly puckish 4-hands Moran/Barron performance of “Blue Monk.”

For the second half Moran’s Big Bandwagon – his trio augmented by trumpet (Ralph Alessi), trombone (Houston homie Frank Lacy), tuba (the redoubtable Bob Stewart), alto and tenor saxophone

(Houstonian Walter Smith III) – reimagined selections from Monk’s Town Hall Concert, including a superb reading of “Friday the 13th”. These re-imaginations were not afraid to employ some dissonance in Moran’s mix. And this part of the evening is where the video installation really asserted itself. At one point as the band played on, the video streamed an evocative reminiscence by Moran on his personal Monk epiphany, how he first came under the spell of Thelonious from his parent’s record collection and the Columbia Lp Thelonious Monk Composer. At other points the master himself entered the hall, courtesy of his voice in studio conversations with other musicians and producers. In each case the audio was clarified by the conversation conveyed in video graphics, just in case ya’ll didn’t understand Monk’s unique hipsterese. “In My Mind” was the theme of Moran’s reimagining of the Town Hall Concert, a mantra Moran repeated on the video installation by W. Eugene Smith, in much the way Q-Tip’s mantra became “options” during their Friday coupling. As opposed to slavish re-creations, this was a masterful program, one Thelonious Monk would have danced on.