With the melancholy recent passing on to ancestry of trumpeter Roy Hargrove, and amidst all the many recollections of Roy’s tireless will to jam, I was reminded of one of the last times I saw Roy, engaged in a friendly trumpet “battle” with Sean Jones at the 2017 Monterey Jazz Festival. Both were guests of the great Kenny Barron as part of his Dizzy Gillespie Centennial tribute on the Jimmy Lyons Stage. That trumpet confab brought to mind one of the most celebrated trumpet battle royales in the history of recorded jazz – the performance that begat the now-classic Blue Note recording aptly titled The Night of the Cookers, a fabled evening that found Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan squaring off on the bandstand.

Several years ago, as part of a series of Brooklyn-centric jazz oral history interviews I conducted for the Weeksville Heritage Center, a project directed by my good friend and cultural anthropologist Jennifer Scott, we sought some insights into one of the most famous jazz recordings ever made in Brooklyn. (Historically, Weeksville was the first African American settlement in Brooklyn.) There are likely some who sleep the fact that The Night of the Cookers happened in Brooklyn, at a long defunct club called La Marchal, proving once again that one never knows where jazz history will take place! For insights on that momentous evening, we interviewed two of the sole surviving musicians who played that date, pianist Harold Mabern, and bassist Larry Ridley. In the customary manner of oral history interviews, we started with some background.

Where did each of you receive your music training?

Harold Mabern: I got my training from what I call from the university of the streets of Chicago. I hung out, made all the jam sessions; Frank Strozier, Booker Little and I spent a lot of time together and we stayed there until ’59. We formed a group with Walter Perkins called the MJT+3, with Bob Cranshaw, yours truly, Willie Thomas, Frank Strozier. They had two other [MJT+3] groups, with George Coleman, Booker Little, Paul Serrano, and Muhal Richard Abrams; but the group we had was the most successful one. So we stayed there until ’59, then we left and all headed to New York City.

Larry Ridley: I started playing the violin when I was five years old back in Indianapolis. I came up in a family that was very much involved with jazz. My uncle, Ben Holloman, was a good friend of Eubie Blake, so I got turned onto jazz at a very early age. I started playing and Freddie Hubbard, Virgil Jones, Mel Rhyne and a whole bunch of us started playing together as teenagers and my first group was called the Jazz Contemporaries, and Freddie played trumpet, Jimmy Spaulding played alto, tenor and flute, and Paul Parker was the drummer, along with first Walt Miller then Al Plank on piano.

I came to New York in 1959 after going to the Lenox School of Jazz, studying with Percy Heath, Max Roach and all the guys that were there. Then I moved to New York to play with Slide Hampton’s octet in 1960.

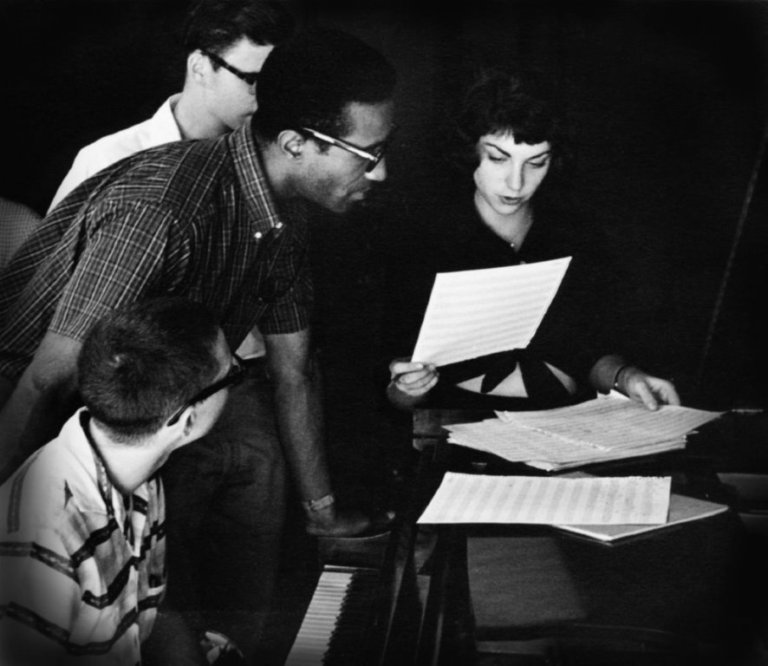

Max Roach schooling students at the Lenox School of Jazz

Leading up to this [1965] date “The Night of the Cookers”, what had you each been doing?

HM: Before then – I don’t remember what time we joined Freddie Hubbard’s band, because we were working with Freddie’s band at the time of that The Night of the Cookers. When I came to New York the first place I went to was Birdland, and Cannonball Adderley was out front. He knew me from Chicago and he said ‘you want a gig’? I said yeah, so he brought me downstairs; Pee Wee Marquette [Birdland’s legendary doorman] tried to bar me, but Cannonball said I was with him. Harry “Sweets” Edison was working there that night, and every night at Birdland was like New Year’s Eve, as Larry will tell you. Tommy Flanagan was getting ready to leave with J.J. Johnson, so Sweets said ‘you wanna play?’ I said yeah, and I sat in and played and Sweets called a song, he said “Habit”, 8 bar introduction in A flat. I didn’t know what the heck “Habit” was, so I fumbled through the first course and by the second course I had it and he said ‘you got the gig’; I was being auditioned on the spot, I got the gig right there and went right back to Chicago.

That was my first gig, I stayed with Sweets then I came back in 1960 and sat in with Lionel Hampton, stayed with him for about a year. Cedar Walton invited me down to Birdland to sit in because he was leaving the Jazztet to go with Art Blakey’s group, so I sat in with Art Farmer-Benny Golson [the Jazztet leaders] and they didn’t make any promises, but they said if we hear anything we’ll call you. They called me the next morning and I got the gig with the Jazztet, stayed there for awhile then I joined J.J. Johnson in 1963, right before I played with Miles Davis. I went on a tour with Miles on the west coast in 1963, with George Coleman, Frank Strozier, Ron Carter, Jimmy Cobb and myself. Before then I had been doing things with Betty Carter. I don’t know if Larry Ridley remembers this, but we went out with Roy Haynes‘ Quartet. After that I just kept doing different things.

LR: I came to New York with a gig; I joined Slide Hampton’s Octet in Pittsburgh and then we came into New York. I ended up working with Slide at different places, like the Half Note and many other different clubs in New York. It was doing that time playing at Birdland that Philly Joe Jones took me under his wing and I started doing a lot of things with him, then I ended up working a lot with Lou Donaldson, Art Farmer, and a whole bunch of folks. As Harold was saying, we were working with Freddie’s band and we always enjoyed playing with each other, [with] Pete LaRoca [on drums]. I think [drummer] Clifford Jarvis played with us for a minute and then Pete came in. Also I was working some gigs with Lee [Morgan]; George Coleman was the tenor player, Louis Hayes was the drummer, Cedar Walton [piano], so we were doing some gigs.

We all were playing a lot and interchanging with a lot of people; I guess we were the young Turks arriving on the scene so we would get a lot of different gigs. It was like a little fraternal situation with all of us because we knew each other, we loved playing with each other; it was great, it was really a fantastic period.

Before this session that led to The Night of the Cookers, had either of you been playing anywhere in Brooklyn?

HM: Larry probably had played [Brooklyn] more than I had. I think I played at the Turbo Village one time and I played [in Brooklyn] mostly at the Blue Coronet at the time a few times, sat in with Dexter Gordon, Blue Mitchell, and Jackie McLean.

LR: When I first came to New York in 1959 I went by the Turbo Village and sat in, that’s where I met Tommy Williams and Andrew Cyrille. Then when I moved permanently to New York I ended up working a lot… Harold and I did a lot of things together; I was working with Barry Harris… that was really a hot spot in Brooklyn, the Blue Coronet. I ended up working with Jackie McLean, when he had Tony Williams playing drums.

We were working with a lot of different people. In Brooklyn there was a lot of stuff going on; there was the Club Baby Grand where some of the guys worked. Rector Bailey used to get a lot of gigs [in Brooklyn].

Were there any differences in the audiences in Brooklyn from when you worked in Manhattan, in terms of the response or just the overall feeling?

HM: I’m sure Larry and I come to the same conclusion, but my first thought is yes and no. The people in Brooklyn were hip, if you played for the people – which didn’t mean you had to downplay your talent. The places [in Brooklyn] were packed and there were clubs everywhere. For me, once I left Brooklyn no matter where you went, you’d always end up at the jazz corner of the world; when you get through doing whatever you were doing, Birdland was the icing on the cake.

LR: The whole scene really was an extension between all the boroughs. Working uptown [Harlem] was always hip, working at Count Basie’s, the Club Baron, the Blue Coronet in Brooklyn, up in the Bronx there was the Club 845; so we were all working at all of these different clubs. So my impression was, yeah there were hip people in Brooklyn – naturally people from each of the boroughs had their own parochial chauvinism going on, but it was basically all the same; particularly being someone who was – for lack of a better expression – an expatriate coming from Indianapolis, Indiana to New York it was all one big thing to me in terms of the places we could work. There were all kinds of jam sessions going on that we could play at, there was a lot of good stuff happening during that particular time.

Would either of you say there was more of an African American audience in Brooklyn?

LR: Harlem was the same, and even in the Bronx. That’s what I mean by the African American [audience] thing, it was pretty extensive during that time. I worked with Randy Weston during that time, with Booker Ervin and Scoby Strohman,

This place where “The Night of the Cookers” was recorded, Club La Marchal, was that a place that was presenting a lot of jazz, or was this just a one-shot deal?

HM: Larry can speak more about that as far as the club itself, because up until that night I had never even heard of it before.

LR: It was a club that wasn’t really noted for presenting a lot of jazz. But how that came about was several of the musicians that were living in Brooklyn, like Bobby Timmons’ wife Stella, and Freddie Hubbard’s wife at the time Brenda, and Cedar Walton’s wife, they had a [social] club — and Charles Davis’ wife, I think she was involved as well – they had formed a club called the Club Jest Us. They were musicians’ wives who wanted to do something to promote their husband’s careers and so they rented the Club La Marchal in order to present this evening, which ended up being called “The Night of the Cookers” and that recording. Freddie had the foresight to record that; Orville Bryant did the recording and then what came out on the recording was Rudy Van Gelder remastered it from the original tapes [Orville] had put together. I thought at first that the early mastering of it by Rudy, to me it lost some of the fidelity that Orville had gotten, but Rudy remastered it later.

From what you’re saying this is not the kind of thing that happened at Club La Marchal regularly.

HM: Not from what I know, because if it had been I would have known about it. So as Larry said this was kind of a one time thing that they decided to put together, with the musicians’ wives.

Who owned this place?

HM: I have no idea.

LR: Neither do I. Again, I think this was a venue they [the social club Jest Us] scouted out and found that it was a place they wanted to produce this concert.

Can either of you recall Club La Marchal physically?

HM: The only thing I remember about it was that it was very small, it wasn’t that big.

LR: I don’t remember any real specifics about it; all I remember is that we had a good time.

How many people do you think were there that night?

HM: It was filled to capacity, if you had 100 people it was a packed house. It was a real small place right on the corner.

Talk about the audience participation that night.

HM: The audience was great, and I would say you probably had 98% African American people in the place that night. Audience participation was great; during that time all audiences were great, but there were a lot more black people involved because what we played they could relate to. When that free stuff came in we drove the people away; like Lou Donaldson said, you gotta play the blues for the people. Anything you play can be bluesy if you’re doing it within the right context.

The audience at Club La Marchal that night for “The Night of the Cookers” was that kind of a typical Brooklyn audience or was it different from what you had experienced at other Brooklyn establishments?

LR: There were a lot of Brooklyn fans that would hang around all of us, and they supported us, which was beautiful at the time. They were very receptive and they were into all of us as musicians, they had the records, there were even some of these guys that had listening clubs. There was a group that Jim Harrison was involved with – some transit workers, Nat White and all those guys – and they would follow whatever was going on in town and they used to have listening sessions at each of their houses where they would just listen to records and get into the music. They were just one among many that were always supportive, always on the scene supporting us, which was beautiful.

That performance “The Night of the Cookers” was so exceptional that it made a memorable record. What role did the audience play in inspiring those performances that are on that record?

HM: For me, it may sound like a contradiction, we were glad that the audience was there but it wouldn’t have mattered if nobody had been there because I motivate myself. The fact that they [the audience] was there was good but I didn’t really need the audience to motivate me. A lot of the musicians need that, a lot of musicians if it’s not a packed house they can’t play. I’m self-motivated, if there’s nobody there but me I’m gonna play as though I have a thousand people [in attendance].

LR: I totally agree with that Harold because we were all self-motivated, that’s why were involved in the music. We came to New York and we were around the giants, it was such a fertile period. We were having a ball just playing with each other, so whatever transferred to the audience… they were there but that wasn’t the primary motivating factor of what was going on, we enjoyed playing with each other. With having Freddie [Hubbard] and Lee [Morgan] together, as well as Jimmy Spaulding, and Big Black was there laying it down… we were just having a ball!

Not every live recording is as memorable as that one. What was it that made The Night of the Cookers work so well, as both a live experience and a subsequent recording?

HM: Two things: you had two of the most talented, most charismatic musicians that ever lived [Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan]; they had charisma but they were musical geniuses on their horns. Freddie said in DownBeat that he used to follow Lee around just to get his overflow with the ladies. Like Art Blakey used to say, when you walk on the bandstand they see you before they hear you. The minute that Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan walked on the bandstand, we had the audience [full attention] then. The audience loved the way we looked; we had a dress code, we always looked good with shirt & tie…

LR: Our main focus was just making the music happen and swinging. [Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan] were two of the young Turks who were setting the pace. In looking back in hindsight I reflect back because Booker Little was right there, but he passed. It would have been nice for The Night of the Cookers if Booker had been there as well, because we would have really taken off! Each of those guys had their own style and approach, but they all could swing and play their butt off.

HM: And they all respected each other.

Since Lee Morgan and Big Black were in a sense guests on this date because you guys were part of Freddie Hubbard’s regular group, how did Lee Morgan and Big Black come to make this date?

HM: Freddie invited Lee to play. If memory serves me right Lee had just finished recording The Rumproller [Blue Note], that’s how that came about. Freddie always loved drums so it’s no surprise that he would have Big Black on the date. Then again when he invited Lee to come on and play none of us had any idea this would be a historical date.

Big Black brought another dimension to that date.

LR: Big Black was a very strong character. I met Big Black through Randy Weston. He was on the scene and he was going around making his thing, then he wound up moving to California.

I ask that because back then having a hand percussionist on an otherwise straight ahead date was kind of unusual.

LR: He was on the scene and we all knew him, we had played with him on other circumstances. He was just a welcome addition to the thing, I don’t really remember what motivated Freddie to include him, but it worked. He just added that special touch. At that same time the Palladium was going – Machito and Tito Puente – it was that whole amalgam of what was happening with that whole thing, as Randy Weston always refers to that Mother Africa influenced all of that. So there was a lot of interplay with many of the Latin cats – Armando Peraza, Patato [Valdes], Tito Puente – it was all still a part of the whole mix of what was going on musically, the whole environment that was happening.

Harold, you played with Freddie Hubbard at the point “The Night of the Cookers” date was made. Was it that particular date that led to your later playing with Lee Morgan?

HM: Probably so, because I think during that time a lot of musicians were in and out of day jobs. I think after that I got a job at Alexander’s department store, and shortly after that I got a call from Lee Morgan, so I’m sure [The Night of the Cookers] had something to do with it. Plus Larry and I were on a date with Hank Mobley called Dippin’ and Lee always loved piano players, no matter who they were… I’m sure being on Freddie’s gig enhanced it for me to get a chance to play with Lee because I joined Lee shortly after that. I tell the kids ‘don’t leave the job, let the job leave you’, I’ve never left a job, and I always stay with the job and ride it all the way.

Who determined the set list for “The Night of the Cookers”?

HM: Freddie called the tunes because it was his band. Those tunes we had been playing a little bit before, “Pensativa” and “Jodo” and all those; Lee jumped in with both feet and did a wonderful job.

LR: Freddie controlled the compositions that we performed, the order and all that.

Did this combination of musicians ever work together again?

LR: I don’t think we ever did anything together again, particularly with having both Lee and Freddie; that was a one-time event. That was just a special occasion; Freddie came up with that whole idea of having Lee and I have to give the boy credit, he pulled it off.

Its not often that you find two trumpet players working together like that. Was there any clash of egos or any rivalry between Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan at the time?

HM: It was called friendly rivalry; then it was competition without animosity. Nowadays it’s competition with animosity, and those cats with their thousand dollar suits couldn’t play “Here Comes the Bride.” All the musicians felt the same way about each other. It was rivalry, but it was friendly rivalry. They learned from each other, they loved each other.

LR: I agree with Harold. There were so many guys that could play their butt off, and they respected each other. One of the things that each of these guys had – it’s not like today with the clones playing each other’s licks and whatnot – each one of them had their own stylistic parameters they would work from, we all do. We never looked at each other as rivals. We just respected each other and everybody was going for their own individual signature, and that’s what made each of those guys so great. Freddie sounded like Freddie, Lee sounded like Lee, on and on…

Back to The Night of the Cookers, I’d like each of you to reflect on that and tell me what are each of your most lasting memories.

HM: I feel very fortunate and blessed to have been part of something, since it wasn’t really planned. Having a chance to work with two of the finest musicians on the planet… and they both were very supportive of me, they always did everything they could to encourage me; and that’s what you don’t find nowadays with the younger generation, not all of them.

LR: I agree, I feel very blessed about it. You can’t really predict a lot of things that happened; the thing I remember most generationally about coming up at that time was that we were very fortunate that we had so many masters who would take us under their wing.

Do either of you have any particular thoughts in closing on why The Night of the Cookers has remained so resonant?

HM: Not to be redundant, but it was about the quality of the music and the wholesomeness of the people who were involved.

LR: Sometimes some of the people that write about the music have not been able to ascertain some of the esoteric aspects of it. I feel that you have a charge that’s ordained to make sure that our perspective is included… As Randy always says, it begins with Mother Africa through the African American experience and the African diaspora… and that’s the legacy and heritage of this music; not taking anything away from any other ethnic group, but it’s just a matter of people understanding the roots that led to the fruits.

4 Responses to Night of the Cookers