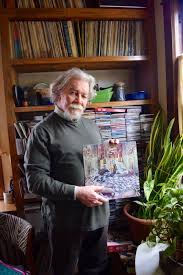

If you missed Part 1 of our oral history interview with Rusty Hassan, just scroll down. Part 2 picks up at the dawn of Rusty’s now 50-year stint as a jazz radio programmer.

Willard Jenkins: After this guy you met at the bar … With the records. What prompted him to say, “Why don’t you come over and do some radio.”

Rusty Hassan: It was our conversation about the music. I don’t remember the guy’s name. I never saw him again. He went and did his class, but he got me into doing the radio.

So, when he said that, “Why don’t you come do radio?” What’d you do about that?

I went that following Monday, he showed me what to do, and at that time they had somebody engineering the show and you were behind a booth. You’d give the engineer the records. I had records to bring, but then there was a library. They had jazz albums as a part of the station’s library.

So this guy actually trained you?

Yeah. Well, he did one show with me and said, “You’re on your own.” There was that initial nervousness when you think about people out there listening and stuff like that.

How did you become a permanent part of the station, it’s not like you can walk in off the street and do a radio program.

Well, I took over the spot that he had. He said, “This is my successor here. He’s doing my show.”

So that’s how he introduced you to the station management?

Yeah, and they said, “Fine.”

Did you have to be a Georgetown student to produce a show?

At that time, yes, but there was a transformation that occurs with GTB, which is why it went off the air, and I’ll get to that. But at that time, it was a student-run station and it was off the air in the summer time. I had graduated from Georgetown and I had no vision of doing radio anymore in 1967, but when John Coltrane died, there was no WGTB on the airwaves. I didn’t even have a working record player at that time, so I went over to a friend’s house to listen to all my Coltrane stuff. At that time, WGTB had a jazz show every afternoon from about 4:30 to 6:30, called Emphasis on Jazz.

So this is how you got started in radio?

Yeah. I did mine [show] on Monday, somebody else was doing the other days. So I started my Junior year, and I went back to it when school started my Senior year.

What was the duration of your program?

Two hours. When I graduated in ’67, oh God … 1967 was an incredible time. Vietnam War was at its height. I had been living off-campus, so there was a mixed group of people, students, people who’re involved with SNCC, older African Americans who lived in the neighborhood. These were my circle of friends in ’66, ’67. The summer right after graduation, a friend of mine, John Reddy had been involved in SNCC, a white guy working in Southwest Georgia in the Summer of ’66. He had met Mrs. Fanny Lou Hamer. He said, “Look, me and another friend of ours, Ed Seizer, we’ll be in Louisville. Can you drive down? We got clothing and other articles [to donate].” One of the friends in the circle of friends was this guy named Willy Kretcher. He’s in his 50’s at that time. Real street person, you know. He and I were gonna drive down to Louisville, and then John’s father had been a writer for the Reader’s Digest. He ghost-wrote Jack Paar’s books and stuff like that. So the other person going to Louisville with me and Willy, was Randy Paar, Jack Paar’s daughter.

We drove from DC to Mississippi, stopping in Chattanooga to hang out. We were drinking. We had a stash of liquor. We stopped and got some more along the way, and Willy liked to press the needle, so it was the scariest ride I’ve ever had. But in Louisville, Mrs. Hamer was still registering people to vote. Conversations in her living room were things like, “Well, you know I know why Stokley saying what he’s saying in terms about Black Power and the revolution, but that’s not gonna happen here. What we have to do is register people to vote, and vote these other people out. We gotta do this for the long haul. It’s not gonna be any quick transformation.” Stuff like that. Gave me a perspective. It was one of the most telling moments of my life to meet someone like Mrs. Fanny Lou Hamer.

We rode back after a couple weeks of knocking on doors and stuff like that. Registering voters and doing some things. Back in DC that summer … ‘67, when John Coltrane dies and I’m not on the radio. Wondering if I’m gonna get drafted, because I was 1A. By the end of that summer, a friend of mine, one of the SNCC folks, said, “Well, you know the National Student Association’s got this program called Campus Community Organizers. Talk to them.” So I did. I became involved in the Vista Program that would involve students in community programs, still tied to Georgetown University. So when the semester started in the Fall, and I was in this Vista program, which was kind of screwed up because I wasn’t getting money yet, but I stumbled back into doing my radio show. I’m a graduate, WGTB’s back on the air, well here I am. They said, “Okay. Keep doing your show.” So I kept doing the show as a Vista Volunteer.

One of the community organizations that I hooked up with as a Vista Volunteer was called the New Thing Art and Architecture Center. Its Director was a guy named Topper Carew. He later did a TV show and a Hollywood movie called DC Cab. I interviewed him on my ‘GTB radio show. I’m a Vista Volunteer doing radio. I interviewed [saxophonist] Noah Howard, who I met up in New York. I started getting into the more avant-garde music of that era.

Were you programming the so-called avant garde on WGTB at that point?

Yeah, absolutely.

Talk about a typical program that you’d do on WGTB.

A typical show on GTB would be playing albums that I was really into at the time. John Coltrane’s “Live at Birdland” with Afro Blue, Willis “Gator Tail” Jackson, with stuff that he was doing. Then I discovered an album called “As If It Were The Seasons” by Joseph Jarman. So I’m getting into the AACM Recordings, also playing those on the air. Older stuff, Lester Young, Count Basie, I’d do a variety of those.

Did you have any particular influences on your programming style?

I don’t think so, quite honestly. Symphony Sid and that type were more personality driven. I was listening to Felix Grant on the radio here, but I was sort of counter. Felix would talk after every tune. I would segue stuff. I’d play way out stuff that he would never touch, because I’m able to do this. No program directors telling me not to do it.

The legendary Symphony Sid

There was no program director at WGTB?

Well there was, but he didn’t tell me what to do. Then when WAMU came up with the airtime in ’69, it was called the New Thing Root Music Show. Simultaneous to doing the radio, being a Vista Volunteer at the New Thing, I met Sandy Barrett. Sandy was teaching African dance. She was part of Melvin Deal’s African Heritage dancers and drummers, so she was part of the New Thing. One of her close friends at that time was [ancestor poet] Gaston Neal. So we had kind of a rocky introduction, and then we became very close friends after a while, but it was a testing period for all of us.

So that’s when you met Sandy, in ’68?

Another guy friend of mine, Will Majors from New York, was an African-American who was really into music, and for a while there, Will and I’d be going back and forth between DC and New York to catch acts up there and down here. We all went out to see The Graduate, and then Sandy and I just went together after that.

What did you study at Georgetown?

I was an English major. Yeah. It makes me very literate and able to talk well on the radio, I guess, but it worked well. I graduated from Georgetown, met Sandy with Vista Volunteer. In ’68, we have the assassination of Martin Luther King, and the insurrection here in DC, we’re living through that. Sandy got involved with the founding of the Drum and Spear Bookstore with her friends who were involved with SNCC, and I’m on the edge of that. I’m kind of the white outsider, but then [I was] finally gradually being pulled in.

Then we got married in August of ’69, and we went to Europe. Went first to England and stayed with my English roommate and his then wife. We bought an old van, we went and drove down to Dover, took a ferry to Dunkirk, and visited Amsterdam. Then we got to Paris. I had an address for Ambrose Jackson. This is at a time before cell phones, people in Paris were on a waiting list for telephones. You didn’t have a phone. Carolyn said, “No, he doesn’t have a phone, but here’s his address.” Five floor walk-up. We walk up, knocked on the door and nobody was home. We’re sitting there atop the steps, and we hear somebody coming up, and it’s Ambrose. We just hit it off. He just said, “Well, the Art Ensemble’s playing at the Museum of Modern Art. Come on up, I’ll take you there.” He introduced us to all the musicians. It was like an entree in many ways. While there, I borrowed a tape recorder from a reporter from TIME Magazine. I don’t remember how we met him, and I interviewed Anthony Braxton, Leroy Jenkins …

On your GTB radio station, you mentioned interviewing Noah Howard.

Yeah.

Did you interview other musicians on your show?

Not frequently, but one of the other first interviews I had was [saxophonist] Byron Morris, and he had performed at the New Thing. In fact, I interviewed Byron before I interviewed Noah. We started the New Thing Root Music Show, and Sandy and I went to Europe. While we were in Europe, Art Ensemble, Anthony Braxton – there was the Actuelle Jazz Festival that mixed rock with avant-garde jazz – Grachan Moncur, Archie Shepp was there. But also, while we were there, on a double bill presented by George Wein, were Miles Davis and Cecil Taylor. Miles had Dave Holland on bass, I think Wayne Shorter was still with him, and Cecil… At a time when Miles was putting down Cecil [Taylor], but they were on tour together! So I got to see this.

Back at this jazz festival in a circus tent in Belgium, I met a guy, an American who was writing for Jazz Journal and doing advertising copy in London. His name was Fred Bouchard. Fred gave me his address in London… We were there with hardly any money, this old Bedford van. It was December driving from Paris back to London, and my friend Andy was in the process of buying a house or whatever. When I tried to make a collect call to find Andy, his father refused to accept the call, and when we got to London running out of gas, I got ahold of Fred. He answered the phone and he said, “Well, take a cab if you don’t have no money, and we’ll cover it” and Fred put us up.

While I was staying with Fred, we saw Duke Ellington, his orchestra at the big concert hall over there, and when he took us to Ronnie Scott’s, I saw Bill Evans on a double bill. So, musically, with all the other stuff that was going on in our lives at that time, musically, it was incredible. We got back to the states in 1970, looking to get a job.

What were you doing professionally at the time?

Vista Volunteer carried me into ’69. Then we came back to the states, stayed with Sandy’s parents for a little bit. That was not too comfortable. We found an apartment at 18th and Columbia Road. Other than that, I’d be at a friend’s apartment on Florida Avenue. He would listen to me on the radio, he’d say, “Well, it was a pretty good show, but I didn’t like that thing of John Coltrane in Seattle, Washington.” He wasn’t into the way out stuff. I took the Federal Employee entrance exam, and I got a job with the Redevelopment Land Agency, the Urban Renewal Agency for the city. It was a federal agency transferred in DC government. I worked as a family relocation counselor in the ’70s. I became active in the union at the job, became the local president and by 1978, when an opening came on the staff I applied for it and got a job with the Union. All that time in the ’70s I’m doing radio on Sunday afternoon, doing the New Thing Root Music Show at a time when things were really happening in many ways.

This is still at WGTB?

No. This is WAMU.

Let’s go back to WGTB for a moment. Talk about some of your more memorable experiences programming at WGTB.

I’m interviewing Noah Howard, interviewing Topper Carew, playing the music. It’s when I get onto WAMU in the early ’70s, and I have friends who are doing things elsewhere. This guy named Yale Lewis and a guy named Ron Sutton –

What kind of station was WGTB, otherwise?

WGTB was in the ’60s a mix of jazz, classical music, some talk stuff. Pretty rigid…

Besides yours, how many other jazz shows were there on WGTB at the time?

Every day 4:30 to 6:30 with emphasis on Jazz. In the ’70s, after I left the station, it became really radicalized. During the ’70s, Royal Stokes was doing a show there called “I thought I heard Buddy Bolden Say” doing traditional jazz. I was doing bebop and beyond. There was sort of radical programming on WGTB in the ’70s. They had a show called “Friends”. It’s the ’70s and they had a gay show on a Catholic station! They had PSA’s supporting the Georgetown Free Clinic. This drove the Jesuits up the wall! By the late ’70s, they give away the [broadcast] license to the University of the District of Columbia.

WHUR [Howard University Radio] came on the air around 1972; Yale Lewis was one of their first announcers and I visited him with my infant toddler daughter, Aisha in a stroller. Then my other friend Ron Sutton started a show there, and we used to trade off on Charlie Parker specials on each other’s shows. We were very wide open, in terms of not competition, but sharing. WHUR’s playing Jazz… Out of a basement or back room in a record store, [Ira] Sabin’s Discount Records, I received a paper called Radio Free Jazz [ed. Note: the early incarnation of JazzTimes magazine].

So how did you get on WAMU?

Topper Carew’s New Thing Root Music Show, putting a show on the air for him…

And what year was that?

It’s like July of ’69. Sandy and I got married in August, and in September we’re gone. I come back, there’s a guy named Ralph Higgs doing the show, Brother Ralph. He was teaching karate at the New Thing. Ralph started another show, like a midnight show. He said, “Why don’t you do the afternoon show, because I’m gonna do the midnight show” and the station management had no problem with it, because it was an organization doing the air time.

What kind of station was WAMU at that time?

WAMU at that time was very eclectic. There was a Black collective show on Saturday afternoons, same time slot, called “Spirits Known and Unknown”. They had a Latin show, they had a variety of music. Bluegrass was really big on the station at that time.

Were you free to play whatever you wanted to do within that jazz context?

Absolutely. I could play free jazz and [John Coltrane’s] “Ascension” back to back. So, on WAMU in the ’70s, I had about four hours of airtime on a Sunday afternoon, play whatever I want, and things happened. It was really great stuff, personally. When I had these ladies on the show for an interview about their event, they said, “Well, do you wanna come to the dinner dance?” I said, “Sure, it’s my birthday.” So, Sandy and I go to this evening at the Shore Hotel, Count Basie and his orchestra playing. So many empty seats, it’s the night before Thanksgiving, I guess the timing wasn’t all that good.

So at that concert, during the intermission, I’m out in the lobby talking to Hollie West who was then the critic for the Washington Post. We’re out there talking and Sandy comes out, “You’re missing it, you’re missing it.” Count Basie’s orchestra played Happy Birthday for me. Well, at the after party, I had my cigar. You could be obnoxious back then, 45 years ago. When we were leaving, Basie’s sitting by himself in the lobby, they were about to take the bus up to Boston. They had another show, a Thanksgiving Day show or whatever. We go up and talk to Basie. Now, I noticed he had a cigar in his hand, and I said, “Mr. Basie, you wouldn’t happen to have a light, would you? My cigar went out.” He pulls out this big Ronson, lights my cigar, looks at his, and said, “Well, this damn thing’s useless. It’s broken.” So I reach in my pocket, I said, “Here, have one of mine” and gave him the other cigar that I had gotten for my birthday. His eyes lit up and he said, “Boy, do you have great taste.” My best birthday… giving away a cigar to Count Basie!

So what were you doing professionally at the time that you were affiliated with WAMU?

I was working for the Redevelopment Land Agency as a relocation counselor, while I’m doing the show on Sundays.

Relocation counselor; what did that involve?

It involved people being displaced either by overcrowded conditions from the code enforcement section, or by urban renewal of the 14th Street Corridor. That whole area right now that’s been gentrified, big malls with the Target. That was all desolate area in the 1970’s. So I’m doing that during the day to make a living, and raising two girls, and doing the radio on Sunday. Interviewing people like Dexter Gordon, Art Blakey, all these folks on Sunday afternoons.

What time of day were you on?

In the afternoon from like noon to four. One time, it was five when they were shifting. I had a whole afternoon, really stretching it, and had everybody come through. It was great. I mean Dexter Gordon coming in when the Homecoming album was just coming out…

Where was Dexter playing in town at the time?

Blues Alley, primarily.

Was there much of a jazz concert scene in DC back then?

The Kennedy Center was presenting jazz, but it was very sporadic. It wasn’t until Billy Taylor, who really solidified that jazz program there. Sometimes there were concerts at the Lisner Auditorium or [Howard University’s] Crampton Auditorium. I saw Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan playing at Crampton in ’71. That was just an incredible concert, sponsored by the Left Bank Jazz Society.

WAMU was a student station?

No. It was a station run by the University… with actually, very little student involvement. Lee, and Russell Williams were Black students involved, and they did workshops. They had people coming through to do training and stuff like that, so that was one of the student components on that [station]. Otherwise, they’d have the Diane Rehm [talk] show, and predecessors to that. While I was there, Rob Bamberger came on the air with his Hot Jazz Saturday Night.

Did societal elements influence your programming at WAMU?

Yeah, yeah… Playing music that expressed the civil rights and Black power struggles and things along those lines. Playing the music of Archie Shepp would be a part of it. Then having the opportunity to meet my heroes. Things were wide open. I already mentioned, WHUR played jazz during this time. There were meetings to set up WPFW. I participated in those. After ‘PFW went on the air, I participated in events, but I didn’t wanna leave the airtime on WAMU. I felt that more stations playing this music was better for the music. Why would I give up WAMU to go to WPFW?

WAMU… where you have four hours.

…in the afternoon. WAMU expanded the jazz programming around 1980,’81, to do an overnight jazz show.

Did you do that?

They offered it to me, and I was already working. I shifted to work for the Union, and the pay was so awful, it was a no-brainer. I said, “I’ll do Sundays. I’m fine with Sundays. I got a career, I got a job paying the bills and stuff like that.”

Were you paid at WAMU?

Yeah. Ultimately, I was given a quarterly stipend.

What was that like?

Rusty Hassan: A couple hundred bucks a couple months… It was beyond volunteer, it was some money.

Where’d that money come from?

The University. I wanna get into another aspect of my jazz life, because long after I left Georgetown, they offered a course and I could have gotten an A. At Georgetown I took a music appreciation course with the music critic Paul Hume and I didn’t get a very good grade in the course. What happened was that he had a gazillion students and he decided to make it real hard. He was really pissed, and I deserved the D+ that I got, but years later when I’m on a music panel with Billy Taylor for National Public Radio, there’s Paul Hume. I told him how I took Music Appreciation at Georgetown when I was there, but I didn’t tell him what kind of grade I got. He said, “Oh, yeah, well you know Paul Anthony also took that course.”

Somebody started teaching Jazz History at Georgetown, and I said, “Well, I’m gonna go check this out.” The guy was a bassist with the National Symphony. His name was Dick Webster. I had just got a bass, and so he gave me a lesson. I checked out the class, so we developed kind of a friendship. At some point he said, “Look, Rusty, I’m in a bind. The symphony’s going on tour. Can you do the class for me?” He said, “By the way, if you like it, the Continued Education Program is looking for someone to do a class at night. My day job’s at night and I can’t do it. We’ll do a proposal.” So I did his class, and I did the proposal, and I started teaching at Georgetown School for Continuing Education, a non-credit class. A couple of months, eight weeks maybe, I started teaching Jazz History.

Who was taking this course?

Adults. Adults wanted to take something. They’re even taking a Shakespeare class, you can take this, take Jazz Appreciation …

So it was like Continuing Education?

It was Continuing Education. Georgetown School for Summer and Continuing Education. So I started teaching there…

A No credit course?

No credit. Non-credit, no term papers, no tests. It was fun. Somebody from GW calls me and says, “Well, can you do the Jazz History class? We need somebody to take it over.” I said, “No, I’m working during the day.” Somebody from American University calls me up. It’s the early to mid ’80s. “Can you do the class?” I said, “Well, I’m working during the day. If you can switch it at night.” They said, “Yeah, what night?” “Mondays.” So they scheduled [the class] Mondays at 5:30.

In the ’80s and ’90s, I taught at AU on Monday nights, did Georgetown another night, somebody asked me at the Smithsonian. I did a couple of courses at the Smithsonian over the years. Did one course where it involved musicians. I had Andrew White talk about improvisation, I had Keter Betts talking about his career, I had Paul Hawkins talking about Latin Jazz. I had all these musicians come in… That was fun. From the early to mid ’80s to the early 2000’s, I was at AU every Monday for Fall and Spring semester.

How long were you affiliated with WAMU?

I was with WAMU until 1987.

What brought about your departure?

Change in the format, new management at the station.

Were they no longer broadcasting jazz?

The only jazz they kept was Rob Bamberger’s Hot Jazz Saturday Night. By that time, WDCU was well-established, and [GM] Edith Smith contacted me –

Back to WAMU for just a second. What was the local jazz scene like in DC when you were at WAMU? And were you a part of that scene?

Oh, absolutely. You got the clubs I mentioned, One Step Down bringing in musicians. Ann would bring in Benny Carter. People of that stature, it was just amazing. Blues Alley had the Heath Brothers, Rahsaan Roland Kirk… There was just an incredible thing going on with the clubs. More of the area artists playing in [DC’s] Northeast clubs… Wise and Moore’s Love and Peace. I was interviewing people, I was emceeing… One of the neatest times in the early ’80s, was when George Wein took over the Kennedy Center as part of whatever his festival was called. Kool Jazz or something like that… They took over the whole Kennedy Center, and I was the emcee in the Opera House.

What year was this?

’80, ’81, I’m not sure. I have to check that out, but the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Band, Art Blakey, Freddie Hubbard… That night, the last act was Lionel Hampton. He didn’t wanna stop, we were told.

Couldn’t get him off the stage, right?

I was making connections with the musicians. We would do crab feasts over at the house, and I’d have Roy Haynes come over when he’s playing at the One Step Down. The Heath Brothers, when they were playing at Blues Alley. Jaki Byard…

How long after you left WAMU did you become affiliated with WDCU, and how did that affiliation come about?

It came about right away.

You said that basically what caused your divorce from WAMU was the change in format.

Absolutely. They were changing the format… and WDCU had been on the air then about six, seven years. [Station GM] Edith Smith called me up, said, “Why don’t you come over? You can have Sunday afternoons.”

Was it 1987 when you started at WDCU? What kind of station was DCU at the time?

All jazz. They did a talk show, and they did rhythm and blues and gospel.

WDCU was known as Jazz 90 at that time.

Jazz 90. It was really, they had consistently the same announcers every day during the week: you had Candy [Shannon], Gwen Redding, all these folks. Bill McClure doing the evening shows. Whitmore John. It was very, very focused on the music.

Here again, you find yourself at another University affiliated radio station. Though, in the case of WGTB and WAMU, you characterized that those universities had a benign kind of relationship with those stations. Was it similar at WDCU?

Absolutely, the station was self-contained, they had all of the programmers doing the music.

Was it a training facility at all, for students?

They did some things like that. They tried to pull it in, trying to develop an interest in stuff like that, they did some workshops and things like that. It was more along the lines of being a professionally run radio station. They paid me, a stipend, more or less.

Who was the WDCU program director at the time?

Wiley Rollins came in.

Did the program director at WDCU exert any influence over what you played until Wiley came in and tried to make things sound professional, and give advice in terms of choices.

So now you’re doing Sunday Afternoons.

What time of day were you on the air?

One to four.

How would you set those three hours up, in terms of your production?

I would focus on who’s coming into town, birth dates, cover the artists that way… By the time I was with WDCU, it was switching from LP’s to CD’s. I’d take a bag of CD’s and have an idea of where I was gonna program it, and then program while I’m doing it. In terms of what fit.

There was a certain element of improvisation in the way you were putting your programs together?

Absolutely. In fact, it was really interesting to me, because here I had listened to Felix Grant all those years, and now Felix and I are on the same station. Not a whole lot of interaction, but I did sit in with him on occasion, see how he had everything scripted, with a stopwatch, really very precise in terms of what he was gonna say and stuff like that. I continued to do what I was doing when I was on the dial in the ’60s.

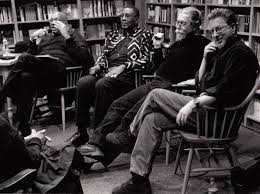

Rusty with DC radio legend Felix Grant, W. Royal Stokes, (unidentified), and Bill Brower

Would you characterize what you did as being kind of the exact opposite of what Felix Grant was doing, where his design was to talk after each selection?

Yeah, in many ways. In terms of looking for more of a freeform FM type of sound… Late ’60s, early ’70s, there’s a shift that went on musically, where music was now formatted in a fashion with these so-called “underground FM stations”. As a jazz programmer, I was able to not worry about the length of a cut, and learn how to segue music so that one piece would flow to another. Even within that context, and still be informative about the music.

Did you do a lot of interviews?

Absolutely. On WAMU, one of the best interviews I had was with Art Blakey. The first time he came and he spent the whole afternoon with me, and it had to be about 1977. Art came in, he flipped the question. I said, “Well, you know … ” I’m trying to say what a thrill it was to have him, he says, “Well, what you’re doing is so important to this music.” Art’s saying this to me! I had the material there to do like a musical autobiography of Art Blakey. What was really great was that afterwards… He was playing at, it wasn’t a jazz club, it was a restaurant right on Connecticut Avenue that would feature a variety of music acts, but not jazz, per se. It was really weird in terms of who they booked, because they had Anthony Braxton play there once. I think the place was called “Child Harold”.

Art Blakey was playing there… I saw him Saturday, we had him come on the show and went back to see him Sunday. He was breaking down his drum set, and said. “Hey, Rusty, where can I get something to eat?” I said, “Art, this is DC. There’s nothing, but my house is on your way out of town.” For me, the shocker was here’s Art Blakey, putting drums in his station wagon. For me, it’s, “Where’s the limo? What’s this?” He had Dave Schnitter and Bill Hardman, John Hicks and a Japanese bassist whose name I can’t remember. I said, “My house is on your way. We’ll fix you up.” Sandy fixed a ham for Sunday dinner. What else have we got? We came in the house, and I found out that Art wasn’t that [Muslim] observant. This is great. John Hicks wanted to stay in the car, so I fixed him a sandwich and brought him a beer, and we were friends after that. John and I became very close after that. Art adopted me. He’d come to town and want to hang, and I’ll never forget one time he said, “Where are we gonna get some Japanese?” I took him to a Japanese restaurant, worried about whether it met his criteria, and it did.

What were you doing professionally at the time?

I was working for the Union, as a staff person with the American Federation of Government Employees. I was doing arbitrations, I was doing contract negotiations, playing group therapist to dysfunctional executive boards, investigating … In essence, doing a lawyer’s job without the law degree. In the ’80s, I got a Master’s Degree, a Master’s of Science in Labor Studies from the University of the District of Columbia. So in addition to [teaching] classes two or three days a week, I’m taking classes.

What got you into this labor work?

It was a political philosophy. When I’m doing the social work, the person said, “We have a Union here.” Okay. You join the Union. Then I became active in the Local at the Redevelopment Land Agency, as home rules come into play here in DC. So I’m involved in lobbying the DC City Council in terms of transitioning from the Federal System to a DC System, and then when the staff opening came up, I said, “Let me do this.”

It was always a matter of looking at something I could do with my progressive politics, and be comfortable with the living that I’m making, and yet doing something that’s going to pay the bills for my household, with the kids that we were raising. My daughters went to DC Public Schools. They went to John Burroughs down the street here, Taft down the street, and then School Without Walls. In the ’80s, Aisha went to the University of Maryland, Kenja got into Princeton. That was financial… What we did was put one of the paychecks aside. It’s a pricey thing even with the financial aid she was getting, but it was a concentration on making sure our kids were well educated. We’re doing the same for our grandkids right now.

Speaking of WDCU, you mentioned this with WGTB and with WAMU, but with the progression of time, what was the DC jazz scene like when you started at WDCU?

At WDCU in ’87, it was a rich scene. The One Step Down was thriving in many ways, in terms of the acts they were bringing there. Blues Alley would bring in an act for a week, from Tuesday through Sunday. The Kennedy Center had Billy Taylor setting up the programming there, so that the major artists are coming through there. It was really a rich scene.

One of the people I became really close to was my father-in-law’s best friend. His name is [pianist] John Malachi. John, as you know, was a pianist in Billy Eckstine‘s Orchestra. They had Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Art Blakey… John, I first heard at a junior high school that Sandy’s mom was teaching at in ’68. He and I really hit it off. He would play at parties at Sandy’s parents’ house. After everybody left, my father-in-law and John would be working on stuff on the piano, and I was like the fly on the wall. Then John would tell me stories that you couldn’t repeat on the airwaves. After that, when I started teaching, John would come particularly to the Continued Ed classes, he’d come and talk about the Bebop era. What it was like to travel with the band, and what [Charlie] Parker was like.

One of the last interviews I did at WAMU was John contacting me to say, “Look, I’m doing a concert at Ellington school. Can I come by and talk about it?” So he came on my show on Sunday afternoon, and he talked about the band touring Florida and how Bird asked him to stay behind. Charlie Parker was working on changes on “Cherokee,” and the two of them jammed on this for hours afterwards. As John was leaving the studio, I said, “Boy, I gotta get more of this stuff on tape. I gotta sit down with you, man.” He was already setting up an interview with Bill McClaren on DCU, and then Bill called me at work two days later and said, “My interview’s off, John passed away yesterday.”

Wow. Huge missed opportunity!

Yeah. I miss him, now 30 years later.

At the time you programmed at DCU, which as you said was known as Jazz 90, what were your thoughts about the fact that given WPFW’s Jazz programming, at that time DC was unusual as an American city offering such a breadth of jazz radio programming. As an active member of the DC jazz community and a WDCU programmer, what was your sense of jazz radio in DC at that time?

I thought it was great, the fact that we still had two stations presenting the music. WAMU was not doing it anymore except for that traditional jazz show with Rob Bamberger. The competition was revitalizing the scene in terms of keeping it vibrant, and it was a friendly competition. I’ll never forget co-emceeing – for whatever reason it was set up this way – but I’m co-emceeing for Ahmad Jamal, with [WPFW’s] Jamal Muhammad out at Ft. Dupont, that kind of thing. Developing a friendship along the way, and making sure that the programming is top-notch, because somebody who’s on opposite you, may be doing something even better.

So there was no sense of competition between WDCU and WPFW?

Well, yeah, it was competitive in a friendly way. Let me tell you. I met [WPFW’s] Jerry Washington when he was living down the hall from Ron Sutton. Then Ron was on WHUR, he was actually doing sports. What happened at HUR was when they shifted to the quiet storm format with Melvin Lindsey, they pushed Ron off the air and made him sports director. Gave him a substantial pay increase, but took the jazz off the evening to change it to the soft R&B that they were gonna do with the Quiet Storm. So then Ron starts doing stuff on WPFW, and upsetting the folks at WHUR a little bit, but then he brings his buddy [Jerry Washington] from down the hall. “Come on, sit in with me. Sit in with me. Now you do it.”

So, Jerry Washington starts focusing on Blues, and creates a persona known as The ‘Bama. WPFW actually didn’t do any counter-programming initially; they had Dorothy Healey on Sunday afternoons, and people mistook the station phone numbers and they’d call me up and say, “Well, how could that lady be saying that kind of stuff? That’s un-American.” I said, “You got the wrong station.” Jerry Washington did the Other Side of the Bama, so he’s doing jazz on Sundays. If ever I had a scratchy record, I said, “Well, this is from the Jerry Washington collection of classic jazz.”

I met [WPFW’s] Nap Turner at a club on 14th and Rhode Island Avenue NW when the hookers were going in and out of this club. What happened was John Malachi had been playing there and had asked for more money for the group, and the guy said no. He then booked a woman named Julie and Nap was playing bass. So I knew him as a jazz bass player, and I watched him develop on WPFW to this personality.

How did you make that shift from DCU to PFW?

Well, when DCU went off the air, I had so many friends who were on the airwaves at WPFW…

What year was this now?

’97.

So you were at DCU 10 years?

I was at DCU 10 years… and all my friends who had been listening to me, like Larry Appelbaum, all these folks who were on WPFW were saying, “We’ll find a spot for you.” Then I became a sub, the Sunday sub for the Rolling with Bolling show. Sitting in for Rick Bolling, or whomever.

This is ’97?

’97, absolutely… Then there was the infamous blow-up between Brother Ah and the then General Manager…

The late Lou Hankins…

Lou Hankins called me up and said, “Can you do Tuesday nights?” I said, “Yeah, okay.” I didn’t know exactly what had happened, but then I ran into Jamal Mohammad out at the VA Hospital, which is one of my locals, and he explained. He had witnessed what happened between them. So I said, “Well, geeze, I gotta do it. Gotta take over Tuesdays.” I was really … I’ve been friends with Brother Ah for years, but I’m not gonna not do this show. Some time later, [trumpeter] Benny Bailey was playing out at Twins, so a week after I started doing Tuesday nights. I said, “Well, let me go see my friend Benny.” I walk in there, who’s sitting at the bar? It was his old friend, Robert Northern sitting at the bar there.

Brother Ah…

So I walk up to Brother Ah, I say, “How come I’m doing Tuesday nights?” He said, “Well, you know Lou Hankins has a failure to communicate.” I said, “Okay.” He had no hard feelings for me, of course, but he said one day we’ll work it out, and eventually he got back on the airwaves.

When you started at WPFW, was your programming any different than what you were doing at WDCU, WAMU and at WGTB?

Absolutely not. I’m blessed. Here I am after 50 years still doing what I started doing as a student at Georgetown. Never had a program director telling me, “No, you can’t play this.” What I have done is edit a bit. I became more inclined to pick and choose from the cutting edge and avant-garde artists, pieces that would be more accessible to a broader audience. I’m sure it’ll turn them off, but I’m going to pick and choose things that will keep a listener engaged rather than turn them off.

Rusty with fellow WPFW veterans Askia Muhammad, Larry Appelbaum, and this writer at a bookstore panel discussion

Would you say that through your evolution with these four stations, that becoming more attuned to what the listener might be interested in, was part of your growth?

Absolutely.

But how did you get that way?

Because of reactions like, “Well, Rusty, I liked everything you played but that [Coltrane] recording from Seattle, Washington.” Then from my own listening tastes, in terms of being very eclectic with it, not afraid to play traditional jazz as well as the avant-garde. To pick and choose what your listener will appreciate. Also, because for all these years I’ve been on listener-supported radio.

It’s also my teaching, the classroom… Playing stuff for the students to get their reaction to it. This is why I can’t do online teaching. I wanna have a face-to-face interaction with the students. One of the things that really made it for me, back in 2010, I was recruited to teach an undergraduate Jazz History course at Georgetown, after participating in a forum that Maurice Jackson had put on in conjunction with a concert with Charlie Haden and they asked me to teach the undergraduate class. I was already teaching at the University of Maryland University College. On Tuesday nights, I’m teaching at UMUC at 7:00, Georgetown it’s four to 5:30 Tuesdays and Thursdays, stealing time from my full-time job to do two classes.

I had [saxophonist] Braxton Cook in my undergraduate class. He was at Georgetown at that time. I’ve had really bright students at Georgetown, really into the music, very interactive with me. University of Maryland-University College is working adults, African-Americans in their 50’s, people in the service and stuff like that. One time I was covering Cool Jazz, playing Birth of the Cool with Miles Davis, with Lee Konitz, and covering that era and [saxophonist-bandleader] Brad Linde had Lee Konitz at Blues Alley with a big band, with Lee Konitz as the featured soloist. I make the students give me performance reports, but I don’t give them specific performances to go to. They have carte blanche. By the end of the semester, they have to give me two performance reports.

So I went to see Konitz, and here’s the Georgetown students coming up, “Oh, great show. I’m glad to see you here.” This African-American woman comes up to me, she’s from the other class. She’s like 50, she works at the post office, I thought she was into neo-soul stuff, whatever. She comes up to me, she says, “Wow, this is great. Do you think Mr. Konitz will sign the picture of him in our textbook?” I said, “Sure, why not?” Now, I meet Lee at the One Step. I re-introduced myself up in the little dressing room. I said, “Would you do me a favor and sign the photo?” He looks at it, “Boy,” he says, “This is an old picture.” I got to see Lee a couple of times since then, and thanked him again.

That really made it for me. That here’s this 50-year old African-American woman coming out to hear this 83-year-old white guy playing the alto sax. It got to her. She became more open with her musical tastes. That’s what I try to do with the classroom, with the radio show; develop an audience for this music that I love.

Up to this point, and I guess throughout your tenure at all four stations, had you worked with any particularly memorable or influential radio program directors or general managers, who were influential on you in terms of what you did on the air?

That’s a great question Willard. The most interaction that I had was with Wiley Rollins, when he came over to DCU.

What made that working relationship so successful?

Wiley, he’d sit down and talk to you in terms of what to do. Earlier at WAMU, there was a guy who sat down with me a while, wanted to tweak what I was doing. Establish the show earlier on, rather than playing a long cut, things that I’d neglected, regressed back to and stuff like that. But Wiley’s point about, “Well, you may wanna play that rare [recording] find and say, ‘Look what I found’ but the sound quality’s so bad that you’re just gonna turn people off. Find the alternative. Find the same artist doing something that won’t turn any of the audience off, in terms of bad radio.”

The thing that I find now is a lot of people just [announce] the main artist. To me, it’s important with jazz as a soloist art form, that you tell the folks who’s playing bass. For a quintet or sextet, that’s not gonna take too much time to run down the whole personnel. You don’t need to name everybody in Ellington’s band, of course, but you wanna be informed about the musicians who are participating in the performance.

What is your overall radio programming philosophy?

I want to just share the music of artists who have been my heroes over the decades that I’ve been doing this. This is an art form that has been marginalized in terms of record sales and audience participation, but it’s an important art form. People should be accessible to it, and open their ears up to it to hear it, so I do the programming on the radio and I do the classroom work to make sure that there are people who understand that this is an important American art form rooted within the African-American community, that has a lasting value and is entertaining, as well.

How else have you combined your radio programming with your teaching?

For years now, I’ve had a listening portion to the mid-term or final exam. I play all of the recordings that are gonna be on that exam, on the radio. Students have an opportunity to hear it on the airwaves, and other folks can take it like it’s a blindfold test in a way. Of course, with your artist identified at the end of the set. I’ve been doing this since the ’80s. I started teaching at American University, I said, “Well, I’m on the air, I want people to identify the artist on these recordings. If I do it a week or so ahead of time, they’ll have an opportunity to listen to these recordings so that they know them.

So it’s optional?

Well, optional in terms of they can listen or they can listen to it elsewhere, but –

When you’ve taught jazz courses, how has the course work interacted with the overall jazz scene in DC?

Because they have to do performance reports, they have to go out and hear artists and come back and do a review… so they’ve been introduced to the jazz scene in Washington. Because they have to identify who’s performing and what they played, and what they thought of it, usually they have to go up and talk to the artist a bit to find out some things. Most of them do.

Willard Jenkins: What would you say is your overall philosophy in teaching jazz courses?

Rusty Hassan: I teach it from a historical, cultural perspective, emphasizing the history of the artists and the roots of this music within the Black community. Rather than being very technical about the elements of the musical performance. A case in point: when I started teaching at Georgetown one semester, this Asian-American woman came up to me. She said, “Well, I don’t know whether I should take this course or not, I see you have a lot of musicians in your class.” I said, “Well, you’re exactly the person I want in the class. I wanna open you up to this music. So, don’t be intimidated, we’re not gonna kill you with technical terms about the music or anything like that.” After she handed in her final exam, she said, “Well, thank you for making this so accessible. I learned a lot and I will continue to listen.”

Willard Jenkins: So basically, your philosophy is cultivating more jazz enthusiasts?

Rusty Hassan: Absolutely.

Down through all these years of being so immersed in the music, what has been your family’s relationship with the music?

When I first met Sandy, she had some fabulous recordings in her collection, including “Ascension” and “Fire Music” that were given to her by Marion Brown, when they were both students at Howard. So she had these recordings, she had Eric Dolphy, one of her favorite recordings. That was an immediate, “Wow, you’re into the music” type of thing, but as I was raising my family, I took my kids out. I took Aisha and Kenja out to hear performances. Both of them saw Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald, either at Blues Alley or the Kennedy Center. One time, there was a whole week of performances that we did with Wynton Marsalis at various facilities, and WDCU sponsored him, we were the emcees. At that time, Aisha was working at an athletic shop in Georgetown, she was about 16 at the time. I took her to see Wynton that night.

I was supposed to tape something with Marcus Roberts, we were up in the little dressing room. Aisha and Wynton were on the couch laughing, joking over Jet Magazine. Then this white woman was in the room. She said, “Well, who are you?” Aisha looked and said, “I’m his daughter.” Not to me, to Wynton. This woman believed it. She said, “Oh, have you eaten yet?” Wynton played along with her, he said, “Well, I want you back before the set’s over.” Aisha went over and she said … What it was, was the woman was hitting on [bassist] Reggie Veal and she came back to Reggie, she said, “You gotta lose her.” The woman kept pumping her for information. She would bite into the hamburger, she told me, she said well she’d make up stuff, but Wynton played along with it, and he stayed in touch for a while in terms of how Aisha’s doing.

Some years ago, we were both judges for the Silver Spring Jazz Festival, the year that Paul Carr‘s Jazz Academy of Music won. I got to show [Wynton] the pictures of our grandkids and stuff like that. So, my girls went out to experience the music. I took Kenja to see Frank Wess where we had a conversation with his pianist about some science project she was doing in Junior High School. Then when my grandkids came along, well you saw me with Caine, every place. From the time he’s a year old and I’m holding him while I’m introducing Randy Weston at the Freedom Plaza Jazz Festival. To seeing Randy a couple of times after that or Sonny Rollins, or whomever. I got a great photograph of my granddaughter Truly with Geri Allen at the Kennedy Center. I’ll always treasure that, now that Geri’s passed on.

Has that made a difference for them?

I think so. They listen to the music, and it’s not their main music, but all of them have grown up with it.

Rusty Hassan can currently be heard Thursday evenings 10:00-Midnight as part of WPFW’s M-F Late Night Jazz strip (full disclosure: this writer holds down the Wednesday Late Night Jazz slot 10:00-midnight), at 89.3FM in the DMV, streaming live at www.wpfwfm.org. Don’t sleep!