With the recent news of early hip hop and scenester Fab 5 Freddy’s collection going to the Schomburg Center, Fred Braithwaite Jr. had once again struck a pioneering chord, by helping to establish hip hop and rap as an archival pursuit for future generations. Several years ago as part of a Central Brooklyn-focused jazz oral history project for the Weeksville Heritage Center, cultural anthropologist Jennifer Scott and I visited a loft space in Soho to interview one Fred Braithwaite Jr. Mr. Braithwaite, better known to the world as Fab Five Freddy, was the first man to deliver hip hop to the television airways via his then-revolutionary program “Yo! MTV Raps”. Fab Five Freddy is the definition of a scenemaker, not only as the man who delivered “You! MTV Raps” to the television airways via the then nascent MTV music video channel, but also through his graffiti-based visual arts activities, and hanging out with figures such as Jean Michel Basquiat, and Fab’s influence in bringing the hip hop sound to crossover figures like Debbie Harry (aka Blondie).

Our interest in including the legendary Fab Five Freddy as part of a series of jazz-based oral history interviews was based largely on his upbringing in the home of a devoted Brooklyn jazz activist and scene maker, his father Fred Brathwaite Sr. The elder Brathwaite had been an ongoing figure in my interview sessions with Randy Weston for the grandmaster’s autobiography African Rhythms (Duke University Press, 2010) whenever the subject turned to Brooklyn, Randy’s development, and specifically the powerful influence of his friendship with another great jazz master, the immortal drummer-bandleader Max Roach. Max, Fred Brathwaite, Jimmy Morton and other jazz enthusiasts and scene makers often gathered at Max’s and other of their homes to play chess and talk jazz. Max Roach is the godfather of Fred Brathwaite Jr. (aka Fab Five Freddy), and it was Fab who first introduced Max to the burgeoning hip hop scene. The prescient Roach instantly saw connections between the development of hip hop and the development of modern jazz, having been one of the pioneers of what was labeled bebop.

Our conversation began with Fab displaying photos of his dad, Fred Braithwaite Sr.

Fred Brathwaite: This is one of a collection of about 20 photos that were given to me by a man named Jimmy Morton. This is part of a series of photos of my dad in Chicago about 1953 at the Beehive. My dad was real close to Max Roach, so this was the trip to Chicago – my dad was accompanying the Max Roach-Clifford Brown Quintet and this was the trip before the next trip, which was the fatal trip where Richie Powell and Clifford [Brown] died. This was way before I was even an idea. Here’s a shot of my dad at my aunt’s wedding in the late 40s, that Brooklyn-West Indian thing.

Since your father was so heavily involved in jazz, what was your earliest recollection of jazz music?

FB: My earliest recollections were jazz being played all the time in the house, along with fiery discussions about everything affecting us as a people – in America and globally – my dad was a big fan of shortwave radio and he would tune in literally to what was going on around the world. I was an early adapter of the Internet and all that stuff and I knew he would have been all over this digital information thing. I continue to understand more and more about what they did as young men, I’m working on the pieces for my memoirs, and I realize what was going on then.

I’ve got vivid memories of jazz being played in the house going way, way back. The jazz station that I can recall was WRVR with Ed Beach, which was the radio station for jazz at this time. Ed Beach was a hipster with a massive collection of the music. I remember as a young kid wondering how could they know whom a guy was just by the instrument that was playing; I would later learn to do that myself. My dad and Max Roach were friends from teen years at Boys High School. Max played in drum & bugle corps, as a kid and then he became this young whiz kid drummer playing with big bands. He quickly rose in the 40s and Max rose to be one of the architects, and my dad was right along with him. There was a group of friends who had formed a little social group that referred to itself as the Chessmen; they developed a love of chess during World War 11 so when the war ended they were avid chess players. And they would gather and hang out a lot.

Max lived in a big, kind of old mansion at 212 Gates Avenue. This house, I understand, had a huge living room and a huge baby grand piano and they would give these sets. As Max became prominent he would bring other Brooklyn jazz guys to come and hang with my dad and his friends. Hence that became a scene of jazz hipsters and frontrunners in Brooklyn, a little known slice.

Was it your sense that this group of guys, the Chessmen, was hanging in clubs in Brooklyn?

FB: Yeah, they were hanging at clubs in Brooklyn. There was the Putnam Central, which I heard a lot about and had been a really big establishment, kind of a premier venue for dances and stuff. Along with having these gatherings – sets as they called them – at the house on Gates Avenue, there was a period of time where my dad and his friends were promoting their own things at this place called Tony’s Grand Dean, which was on Grand and Dean Streets in Brooklyn. I’ve got a series of photos, which I let Robin Kelley use for his Thelonious Monk book, which document that scene.

The interesting thing about these pictures, as with this one – which was in color – it was [using] one of the first 35mm slide cameras, the beginning of that technology and Jimmy Morton had one. It’s very rare to see color shots of jazz guys from the early 50s, everything is always black & white. These slides that Jimmy has given me over the last 20 years document this scene, which I’d heard stories about countless times when the vibe would hit the right pitch at our house and the music was right, my dad and his friends would always go back to things that happened at Tony’s. It was always exciting to hear these guys get really geeked up talking about what happened and I would often times be a little kid playing in the room with my toys and things but would tune in to those stories.

During a critical period for Monk when they had taken away his cabaret license, which as you know was his ability and legal right to play in clubs, so he couldn’t feed his family. So these particular gigs were gigs that helped keep Monk alive during a period when they had taken away his legal right to play [in Manhattan clubs]. Robin even found a little ad in the Amsterdam News archives of one of those gigs at Tony’s that Jimmy Morton blew up and I framed.

A few years ago when I caught back up to Robin as he was about to release the [Monk] book he was telling me all these stories about my dad and I hadn’t recalled telling Robin all this stuff about what happened at Tony’s and my dad’s whole group of friends, later when I asked him he said that Randy Weston had told him all those stories. Randy is still really lucid and remembers everything. Robin was asking me… he said ‘damn Fab, its funny’ – because the photo in the book, which is the greatest of the photos I have [from collection Jimmy Morton gave him] is a photo of Monk in the foreground, Miles, Max, Mingus on bass…

Yeah, I’ve seen that photo from Jimmy’s collection; he has that hanging on his wall and he showed it to us when we visited him, and the original is in color.

FB: People that are aficionados – I’ve got one buddy who is a Miles fanatic – say ‘man, I’ve seen every photo of Miles, what the hell is this?’ Of course I’ve got all these heavy stories… What we found out, which is an extension of the great work that Robin Kelley did, was the reason Robin couldn’t find an ad for the performance that the photo depicts… the reason was because what Robin and Jimmy Morton figured out is that they didn’t take out an ad because it wasn’t to be public knowledge that Monk was performing this gig. Having your cabaret card taken away was like driving a car without a license; if the cops found out you were going to jail.

Having heard the stories about Tony’s and Monk and just dozens of different stories growing up, Robin went in deeper because he interviewed one of Monk’s siblings about the fight that almost broke out between Miles and Monk or Monk’s brother. They were rehearsing for this gig at Tony’s and Miles was trying to tell Monk how to play it and in the book Robin writes about how Monk had to check Miles, it was about to go to fisticuffs [laughs].

You talked about these sessions these guys used to have at the house at 212 Gates Avenue; what were they like?

FB: That was more like jam sessions, the musicians would come and play, and it was just like a scene… I guess the thing that was infectious to me was the enthusiasm and the energy they would have when they would get into those conversations. Jimmy Gittens, who I should say was such a huge, huge influence on me and what I even do now, Jimmy was like a big brother/uncle to me… It was Jimmy Gittens, Lefty Morris, my dad, Willie Jones (the drummer; a major activist)… It was Willie Jones, my dad and them that were together when they assassinated Malcolm X at the Audubon Ballroom. Willie Jones was very active in community politics in Brooklyn and also in Harlem at that time and Willie would always have – the reel-to-reel [tape recorder] was what real jazz aficionados had back then, which I always remember in the house; but Willie Jones had a small portable one, which I thought was really cool.

He would record Malcolm’s speeches, because Willie had a relationship with Malcolm at that critical point in his life. I remember Willie would record those speeches and give a copy to Malcolm, and these speeches would also be circulated amongst their friends so I’d hear a lot of those as a little boy. When Malcolm was killed Willie was recording. One of the first bullets went through the microphone of Willie Jones’ tape recorder and the microphone activated the recorder. I remember them many times playing that over and over and discussing that tragedy; you literally hear Malcolm coming into the room and [greeting] the crowd, and then you hear a commotion in the distance, and then you hear somebody stand up and yell “get your hands out my pocket…” and that was the diversion and the other guys got up and shot Malcolm. My dad and Willie saw this go down, panicked and ran to the back of the room to hide.

I should also point out that along with all this music being played, and this energy around this music which was always being played around the house — the jazz stations, the music, the tapes, a whole span of music — a discussion of world politics, where we were as a people was also of paramount importance.

Were musicians part of those discussions?

FB: From time to time; Willie [Jones] was always there, and Willie was an activist… He was at my house three days of every week until I was an early teenager; he was like a fixture at my house, along with at least three other guys.

At what point would you say that you became more conscious of what they were about?

FB: I was always conscious, as a little boy I was aware of these things and I would hear these tapes, but I was pretty much still a kid and playing with army men and stuff that kids would do. As I think back to a lot of those things I realize I was more aware than I probably was at the time; I can remember things very vividly and can understand in a broader sense what their main concerns were. I’m a kid with all my issues being taken care of by my parents, so I didn’t get to experience what they knew as a black man you had to experience at that time. Especially when musicians went on the road and how they had to live, the situations these young, intelligent men were forced to deal with when they went out into these different environments and were very actively concerned with making change.

I’m saying all that to say that I also realized later in life that my dad was a big part of Max [Roach]’s consciousness and awareness at that time.

How so?

FB: You hear it in music, it was all further explained to me more when I grew up and as an adult Max would explain these things to me himself. One of my earliest remembrances of a Max Roach record is the “Freedom Now” suite, “We Insist”, that record. One of those records has a photo on the corner of Max and some men sitting at a lunch counter and as a very small boy I always wanted to know what this was about. My dad and them would explain this to me. I destroyed a lot of my parents’ records as a kid playing with them, but the images on those records – there was great photography at that time, abstract art, etc. I would later see those records and I’d be like ‘oh my God’…

My mother had all the jazz singers – Sarah Vaughan, Nancy Wilson, etc., etc., and my dad had a nice collection of a lot of the bebop records and they would listen to them both. But my mother was always into the singers. My mother hung out a little bit with Dinah [Washington], she hung out a little bit with Etta Jones, and I remember the imagery from these records. So if I see them now I’m like ‘Oh my God, I’ve seen this, I know this’. I have a little collection of photos and I think I was developing my visual sense at that time through looking at and playing with these records, but particularly the “Freedom Now” suite. As I grew up and got to understand a little bit more about Max I realized that was one of the first protest records; the beginning of the 60s, the beginning of anti-war protests, the whole cultural revolution that transpired at that time. I realize that Max was at the forefront and my dad’s influence, because when they came to my house my dad pretty much held court. He had read the complete works of Mao, Marx, and Lenin, all of this stuff… He got onto this stuff while he studied economics to be an accountant.

As a black man realizing that we’re not getting a fair shake, nor have we gotten one, he was exploring and looking at these other possibilities before they became the foundations for these other movements. He had absorbed and had an understanding of all this ahead of the curve.

When you say that your dad had an influence on Max Roach as far as his consciousness about movements, explain that.

FB: As I said, my dad had read all the works of Mao, Marx, Lenin, also African nationalists – my dad wanted my middle name to be Lumumba, but my mother wasn’t going for it [laughs], but I later learned who Lumumba was and how incredible these guys were and how a lot of my dad’s ideas were right in terms of alternatives that were much more viable – whether they worked or not in other countries, 30 or 40 years later we can see that those things didn’t pan out as they were sketched out in those books… But that’s what went on at my house. These guys would roll up and do their thing, listen to music, and have these intense discussions and debates. Often my dad would have the most insight because he had read the most and had this kind of broader understanding of what was going on in Africa, what was going on in China… as all these African countries were getting their independence… I guess it was a really buoyant, exciting time if you were an intelligent person who was aware and concerned. If your father had been down with Garvey and that whole [sensibility]…

What is your sense of how the music interacted and spurred some of that discussion?

FB: My sense of it was this… I spent a lot of time sitting around the kitchen table where a lot of these discussions would happen…

…Because the music was obviously more than a soundtrack…

FB: Yes, absolutely… My dad’s den/study was in the basement, where the real shit would go down. Thelonious Monk – as I’m growing and becoming a young teen – I’m beginning to now discern whom the musicians are that I like, that I’ve been hearing forever and ever. Monk becomes that musician; I became fascinated about this whole thing with Thelonious. One day I looked in my father’s phone book and I see Thelonious’ phone number and I call his house and I speak to Nellie [Monk, Thelonious’ wife]…

How old were you?

FB: Twelve, maybe a little younger, I’m not much older than that. Remember, I’m still kinda little boyish because when I think back to that I think ‘God, that’s such a kid thing to do…’ She could tell it was a little boy calling and I said ‘hi, I’m Freddie Braithwaite’s son and I want to talk to Monk, I know my dad knows you.’ She was really sweet and I started talking to her and I guess I was telling her that Monk was a musician that I really liked and in the course of discussing that she said ‘you know Freddie, jazz is like a conversation, and in the beginning of the conversation somebody makes a point and then they go on to explain this point.’ That’s the main thing I remember from this conversation.

I’d been listening to this music all the time and from that I now get what’s going on: the song starts off, the theme is stated, and then these guys all go off and do their own interpretation and you could still hear the theme going through there, like that’s the point. And I got it now, this became really apparent to me and I was like ‘wow, yes…’ and now when I’m hearing songs I could understand them and see how different guys do their thing as they get into the improvisation and all that stuff. But I guess I also began to understand that the guys making this music were really intelligent and really smart and they were really aware of their times, so the music was a reflection of this, therefore the music was an articulation of the intelligence and the point of view of these very sophisticated and modern musicians.

I knew that Max and my dad were in synch with a lot of the same thoughts and the same stuff, and then once I got older I figured out a lot of these things for myself. You just realize that these are very intelligent men and they’re very concerned – although the music wasn’t always about the lyrics, the feelings and the vibes that you could get – I’m not trying to say that all jazz music had this protest, let’s make revolution thing, but it clearly was an affirmation of us as these modern individuals, which I guess is the thing that had the most impact on me because I always saw them in that light. Those conversations that went on, I realize that these particular individuals had a lot of conversations like this. It wasn’t just my dad and his friends, which was happening with a lot of other guys at that level.

I remember later, when I would become a young man and spent a lot of time with Max and things that we would do together, I remember Max telling me how when Olatunji first came over [from Nigeria] how him and Dizzy were so excited about this new thing going on. And I remember Max explaining this to me because Max was a very big, early supporter of me being involved in hip-hop music and culture. So Max essentially instigated us having gigs together.

The way I read it is that some of Max’s early consciousness of what was going on in early hip hop culture was from you.

FB: Oh yeah. One day Max came to visit my dad and asked what I’m into and my dad said ‘oh, he’s into some rapping thing…’ This was before [hip hop] blew up, this was the early 80s when we were having street block parties and what not. I was already making my moves on the arts scene and I was never trying to be a rapper but I had a few rhymes that I could get on the mic at a block party and do my thing. I was not trying to be a rapper. There was a DJ across the street that had built a nice system in his crib so I would go over there and rap a little bit. So my dad was aware of this, unbeknownst to me – and my father was never into much, if any, contemporary music – with the exception of James Brown.

So one day I came home and my father said Max had been there and “I told him you’ve been doing this rap thing with your man across the street…” Right away I get kind of nervous because I never at that point considered anything music with the developing rap scene. I knew we weren’t playing instruments, we were making sounds and we were energetic and I knew this was a new thing that I dived into full speed ahead, but I didn’t consider it music – as in musicians. My father said Max wants to check it out, so I said OK. So we arranged a time a week or two later and he came through, on my block on Hancock Street between Lewis and Sumner – which is now Marcus Garvey Blvd. which is very appropriate.

I prepped my DJ and we worked out a little routine… Once again the music is not formulated – the four-minute rap song is not developed, it’s just in the streets equivalent to just jamming, no real structure. Max comes by and I’m rhyming and my DJ is cutting up, he’s scratching. Max just peeped it. We did a little 20-minute thing and when we’re walking back to the house I’m thinking ‘what the hell is Max gonna think of this shit.’ Max said ‘Let me tell you guys something, that shit that you and your man were doing was as incredible as anything that me, Bird, Dizzy and any of us were doing…’ I’m thinking to myself [skeptically], ‘that’s so nice, trying to placate a young teenager…’ But that’s how Max was, always very encouraging, but I’m thinking to myself ‘yeah, right…’ because I’m not seeing this as music, this hip hop thing…

“Rapper’s Delight” was probably out as a big record at that point, nothing really breaking crazy like it is now. It wasn’t long after that through me now making moves on the art scene and people knowing that I’m doing my thing on the downtown scene in New York, with graffiti, introducing people to the beginnings of this hip hop culture that a guy who promotes a lot of things with performance artists says ‘man, I found out that Max Roach is your godfather… We were talking with him with this M’Boom group…’ And he says, ‘man I feel like why don’t you do something with Max together…’ And I’m like thinking ‘huh, how the hell?

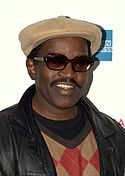

MUNICH/GERMANY – JANUARY 19: Torsten Schmidt (Red Bull Music Academy, l.) talks with Fred Brathwaite aka Fab Five Freddy (Creator) on the podium during the DLD15 (Digital-Life-Design) Conference at the HVB Forum on January 19, 2015 in Munich, Germany.

MUNICH/GERMANY – JANUARY 19: Torsten Schmidt (Red Bull Music Academy, l.) talks with Fred Brathwaite aka Fab Five Freddy (Creator) on the podium during the DLD15 (Digital-Life-Design) Conference at the HVB Forum on January 19, 2015 in Munich, Germany.

Next thing I knew Max says ‘yeah, let’s do it…’ So then I started to have these conversations with Max and Max says ‘yeah, you’re in charge, put this stuff together…’ This is the kind of enthusiasm and how eager they were to check out something new, which is the point that Max made to me. He explained how Bird and the guys were about checking out new things, about how when Olatunji came around they all jumped into the African thing and they were the first [generation] to take African names. He was saying this also to explain how a lot of cats wanted him to continue playing the stuff that they architected back in the 40s and 50s but Max was always saying ‘I’m always about checking out that new thing…’ Obviously Miles was able to put that in full effect. Max had hipped Miles to my show “Yo MTV Raps” and he was checking it out. This was an extension of how Max would always bring me up when the hip-hop thing came up.

Another key thing that Max said to me after I gave him that demonstration with DJ Spy, Max said “…you know music, western music, has for a long period of time been a balancing of three different things: melody, harmony and rhythm in equal ways. As black folks have been involved in music we’re added an increasing emphasis on the rhythm element throughout the development of this music.” And Max, when he would have a conversation like that would always say ‘from Louis Armstrong up until…’ He said ‘what you guys are doing is just totally rhythm…’ Now that’s one thing that when he broke it down I said ‘…oh shit, yeah…’ just grabbing different sounds and cutting & scratching, just grabbing a piece of the music and having a way to manually manipulate the record to have this extended rhythm was something Max heard clearly. He also told me ‘man, if you don’t know it this is so big what you guys are doing…’ I’m like ‘yeah Max, great…’

It wasn’t until like 10 years later when I’m hosting “Yo MTV Raps”… this was ’92 now, and it was the early 80s when I had this conversation with Max. By 1988 I’m the host of the first nationally televised show to focus on this rap music and go around the country interviewing the different people who were defining this culture, everybody from Tupac and Snoop to Will Smith and Run DMC, etc., etc. It would all become so much bigger than I ever, ever could have imagined… I’m talking like on a global basis… where people who speak other languages could adopt this thing and make it theirs in a unique way.

I thought back to what Max had said and how he was right, and how when we get into it we were just gonna embrace this whole rhythm thing, and how just the verbal, this whole rapping thing was interesting.

At what point did the light go on and you realized that this was part of a continuum – that what your father and Max and these guys were into, there was a straight-line continuum to what you and your contemporaries were getting into?

FB: It was during the time that it blew up. I’m hosting “Yo MTV Raps”, which just came out of nowhere, that was never an intention of mine to be on camera doing things, I always wanted to do things culturally to help stir it up and create these bigger platforms… A lot of my ability and understanding of that were things that I absorbed around my dad and his friends; knowing that Max Roach and these musicians were loved more so around the world than here… The fact that I knew people who were big in Paris, and Italy, and Japan was just amazing to me, it gave me a sense of the world as a very young kid.

Hence key things that I would make happen or launch or instigate in hip hop were motivated by those ideas – knowing that, wait a minute, this stuff that we’re doing in the hood, in the Bronx or Brooklyn, is not happening anywhere else in the world. To me that was interesting and I knew it would be at least accepted in other places around the world because these people had embraced and understood the music we were making and put musicians like Max and them on a pedestal on a par with the greatest European musicians ever and I felt that these people would at least appreciate the things that we were doing, because at that time it was not in any way appreciated by mainstream culture here in America. And that led me to then do things which would become very significant.

The first film on hip hop culture, “Wild Style”, I star in, I do all the music for, I collaborate with a guy named Charlie Ahearn on the film… The initial idea I had was to make a film that showed that there was a link between this music, this rapping and DJ’ing, this break dancing and this graffiti art… there were no links prior. I felt they were all very similar and if we could put it together in a movie in a story that depicted it as such, it would create a much more cohesive cultural picture and a look at what we were doing in the streets and the ghettos of New York. There was no positive press or mentions of a young kid with sneakers on and his hat to the side… you were made to look like you were one of those criminals that was destroying the city. So “Wild Style” the movie became this first look that many people around the world had and a spark that ignited them to get busy, and I’m proud of that. Those ideas come directly from the experiences I had being around those kind of individuals [like Max Roach] and knowing that they made global moves.

OK, you were sitting around as a young kid doing your thing and these elders were doing their thing, what was it about what you heard or experienced that inspired you?

FB: I don’t know the specifics, but I just attribute it to… Jimmy Gittens had a huge influence on a lot of that because he was an artist, he was a sculptor and he started this program called the Sculpture Workshop that was a community organization that you could work as a kid and teach people sculpture in the Bed-Stuy area, and Jimmy just loved doing that. So these are my beginning feelings…taking a big chunk of clay and seeing Jimmy carve busts of Malcolm, and King Tut, and just making amazing images of us and things, and then me making something and anything I did Jimmy and all those guys were just encouraging and enthusiastic about. There was no idea or no kind of thing that was beyond at least discussing in my household. Not so much with my father, but with Jimmy and those guys that were kind of an extension of [his dad].

It was Jimmy who taught me how to play chess when I was 8 or 9 years old. I felt like their little think tank if you will. They would be talking about big moves the same way I’m sure Obama and his cabinet talk. They were just the most intelligent men… they were very articulate, they were very hip, they were very slick, they were street, all these things and I guess as those things synthesized in me it was just how I thought. It wasn’t always apparent how connected these thoughts were to what I grew up around, but as I grew older I would realize… and I would constantly think of what I was around as a kid and realize what effect these things had on me. Just knowing that Max was there…

I can remember when I first began to put two and two together and to figure out what I wanted to be a part of, which was the mainstream pop art world, where there was no real precedent of black folks being key in those spaces… It was really like ‘how do I do this…?’ As I began to make inroads and began to get a little exposure… The first art show that I would have… because that was the main thing, not trying to be a musician, but really became the main thing significant for me… I wanted to be a painter… Like the work of Andy Warhol that I had seen as a little kid in a magazine, he looked cool to me… I would find some stuff in art books that made me realize that these guys were inspired by the same stuff that inspired graffiti artists, a lot of us that were painting on the trains… so what’s the difference? I mean we’re getting stuff from comic books and ads just like they did, so what’s the difference? I just had to figure a way to get into the galleries so that people could see me on the same walls they would see like a Warhol or [Roy] Lichtenstein and what not, I wanted to do that the same way that they did.

Through this whole period whenever I would have meetings with Max I would download all this stuff and he would be so encouraging and enthusiastic. The first show that we had, the first press, was at a real prestigious gallery in Rome in ’79. I’m like 19 or 20… it’s crazy.

Did you and Max collaborate onstage?

FB: Yeah, this story I told you about earlier where the guy put us together, that happened at The Kitchen [NYC]. If you go on YouTube you can find a little clip of it, just a piece of it. I’m like, I’m no musician and Max Roach was one of the biggest figures in my life, he’s a musician, how do I even talk music with him? I’m not a musician, but I could make sounds with my mouth. I was so nervous about giving Max instructions, like how do you tell this great master musician how and what to play. I remember at one point we had a conversation after we were rehearsing some stuff. He said ‘man listen, I know its kind of difficult for you to be able to tell me what to play, but man don’t even worry about that, you’re in charge.’ It was unbelievable that he would say some shit like that! I’d have to get my shit together and then figure out how to express it to him.

The one regret was… there’s a recording that I’ll dig up, one of the things that we recorded, and I wrote a rap… You see it was hard for me to instruct Max how to keep like one beat as simply as the backbeat for any one of a million rap records that have been made since then. How do you tell a guy that plays the drums and makes it sound like there are three people playing at once [vocalizes a basic backbeat]… I don’t even know how to do that, it just seemed awkward to say just to do that. What I thought about doing, which we did and I found a recording of that… And this was before sampling was a big thing. I said well what we’ll do is we’ll record and then we’ll loop a recording of what I hear from what you played and I’ll get the engineers to loop that up and make a track of that, and from that track I made a rap over that, which I totally had forgotten that I made this rap: “Max Roach he’s an architect, a pioneer, on the drums he’s an architect, an engineer…” I had fly shit that I just wrote up about Max. When I played it back recently I was like “Oh my God, that’s nice… yeah! But once again it was just unstructured, because the whole song structure [of rap] hadn’t developed and it was just me rapping and Max playing. I think it had a hook and it would have been very interesting had we released it.

It’s hip hop in the sense that… Hip-hop is more like… I mean people call Kenny G jazz, but you know and you would have a problem saying that, right?

WJ: Yep…

FB: Good, me too. Along that line we could differentiate between… like Blondie, something else that I helped make happen, Deborah Harry making “Rapture”, which was the first rap record to go #1 pop, she’s rapping, but that’s not hip hop. Hip-hop bespeaks many things, particularly being part of the culture, adhering to all those things that are just… you know what I’m saying? Like there’s white cats… not to dismiss Kenny G because he’s a white boy, but there’s Gene Krupa, there are a lotta white dudes that you could just feel by how they articulate what they do on their instrument, you’re like OK, dude gets a pass…

I used to love hearing my father and them listening, when I was a young boy… ‘aw man no, that’s so and so, no that’s not him, that sounds like blah, blah, blah… no, that’s an ofay…’ They weren’t dissin’ white people, but it really meant most of the time that they weren’t as up to snuff as most of the official cats. I know that Gene Krupa got some love and there were some white musicians that my father and them would OK, but not that many…

What we did you could say it was hip hop, but yeah I was just rappin’, because it’s me because anything I do is officially hip hop because I’m one of the creators of the brand and what not [chuckles].

One of the things that Max always said about the development of rapping relates to yours being the first generation that was denied the opportunity to pick up any instrument they wanted to learn in school, as a result kids created rap and hip hop.

FB: Great point, key point, yes Max would bring that up, instruments are gone from the schools… Its funny I do a lot of work with VH1 and they have this big initiative called “Save the Music” which is a big charitable initiative where they raise all this money to put instruments back in the schools because kids from this generation are not aware for many generations that [the availability of instruments to learn] was a standard thing in schools, almost a requisite. So you’re right, Max and them would speak to that. It is in a roundabout way one of the things that gives birth to hip hop, this form, this new thing was because kids were not able to develop and become proficient on instruments like many would have wanted to or would have dabbled in to a certain extent. That would be a discussion we would have with Max. He was very aware of things going on as they connected to a historical lineage. A lot of this shit didn’t click then, but I’m glad I remembered it because it all fit into place as the years went by.

Jimmy Morton told us that you have a lot of photographs from back in the day when your father and his friends were active in Brooklyn jazz.

FB: He gave me the actual slides of his color transparencies, and from those I’ve made a few prints; none have been published except for what’s in Robin’s book [Thelonious Monk bio].

What memorabilia do you have from your dad?

FB: I’ve got a lot of his books and stuff, not a lot of stuff. Unfortunately we were not great memorabilia keepers, but I’ve got some things. I actually got to visit Shanghai, China last year and I often tell people to sum it up that Mao was like Jesus Christ in my house, the symbol of him, what he would later mean for a lot of people looking for alternatives… When I went to the big tourist souvenir places where they make everything look old… there was a period after Mao’s demise after the Gang of Four. It was ironic after going to China and seeing that China was able to adapt capitalism while still remaining a communist country, a buddy of mine gave me a BBC documentary and I was able to see the whole story, so it almost took it back to where my dad was still following it. To be there and be able to buy some of the red books and some of the posters that my dad and them had all those years ago, thirty years later, was just incredible for me, it was like coming full circle.

Is there any chance of getting a look at those photos?

FB: Sure, there is only a small grouping of photos, I’ll show them to you, I didn’t know you guys wanted to see them. There are only about twenty and I’m just glad over all those years they still survive. I always thought of something along the lines of what you guys are doing, to kind of tell this story for cats in Brooklyn that most people don’t know about. My dad and his friends were very Brooklyn-centric. It was a campaign about how bad Brooklyn was.

When I was coming up, living in Brooklyn and coming into the city doing the shit that I did was literally no different, except for the living space and Miles of course, than going to California, Manhattan was literally that far away. When you grow up 100% Brooklyn, you might make a couple of forays into the city, or New York – which is how people would call [Manhattan] back then – to see a movie, go to Times Square, or to the Village, was like literally a big deal, that’s how it was when I was growing up.

When I branched off and ventured into the city and connected with the Blondies and the punk rockers and began to set my shit on fire I was one of the few people on the scene who were literally New Yorkers. Most of the people on the downtown scene were from everywhere, like on the art scene; they would come to New York to make it. Me and Jean Michel Basquiat were the only two people that were New Yorkers, which was really cool. When you really know the history Brooklyn was at one time quite a prominent, full on city – a much bigger landmass than the rest of the city. Fulton Street used to mirror 125th Street [in Manhattan]. There a lot of clubs on Fulton Street, which was like our 125th Street; we had the Baby Grand, the Blue Coronet…