One of my earliest off the bandstand encounters with trumpeter, composer, bandleader, educator and curator Ahmed Abdullah came when I conducted a series of oral history interviews for the Weeksville Heritage Center in Brooklyn. Working with my colleague Jennifer Scott, our task was to build Weeksville’s considerable archives with a specific focus on past and present history of jazz in Central Brooklyn. At the time Ahmed was part of the Central Brooklyn Jazz Consortium orbit, along with such good people as the late Jitu Weusi, public school educator and one of the guiding forces behind the legendary Brooklyn performance space The East, the late editor-publisher Jo Ann Cheatham of Pure Jazz Magazine (and a contributor to my 1922 book Ain’t But a Few of Us), Bob Myers proprietor of the former Up Over Jazz Cafe (where young artists like Robert Glasper, Marcus & E.J. Strickland and other players first got their feet wet), the recently passed social justice activist Viola Plummer of Sista’s Place and others. At the time Ahmed was curating the weekend jazz series at Sista’s Place. along with his performing, recording, and education pursuits.

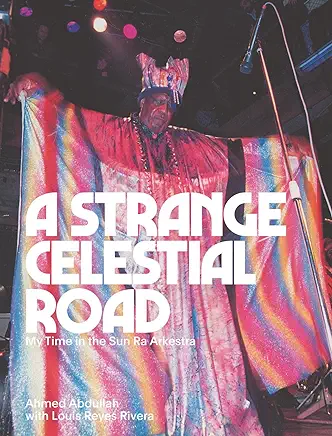

In 2023 Ahmed Abdullah published his memoirs A Strange Celestial Road an engrossing meditation on his development as a musician and person, with a central focus on his many years of alternate high reward and deep frustration as a member of the Sun Ra Arkestra, both pre and post-Sun Ra’s 1993 ascension to ancestry, where vexations were writ large. On the heels of its 2023 Grammy nomination for the album Swirling, and on the cusp of current Arkestra leader, saxophonist Marshall Allen‘s amazing centennial (May 24), A Strange Celestial Road is quite the fascinating and highly-recommended read. For further illumination we recently posed some interview questions to Ahmed Abdullah.

Independent Ear: Recognizing that there are a great number of your peers who might reward the reading public and themselves by documenting their experiences in such a public fashion, besides the inspirations of the overall experiences you document in A Strange Celestial Road, what in particular inspired you to write this book?

I was inspired to write A Strange Celestial Road for several reasons. Uppermost was the fact that the experience I had at FESTAC (the 2nd World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture held in Lagos, Nigeria; one of the planet’s grandest gatherings of Black world artists) in 1977 with the Sun Ra Arkestra, was to my mind completely misrepresented in John Szwed’s (biography) Space is The Place. There was nothing I could do about this depiction of events because [Szwed]’s book was already published. Secondly, I benefitted from the philosophy that had carried him to that point, was not given the kind of attention I would have thought it demanded and since I was an eyewitness to that, I was compelled to write about it.

Thirdly, the [jazz-based] Loft Movement of the 1970s, which ties into FESTAC as events during the age of Self-Determination, needed to be written about from an insider’s perspective, as well. Szwed’s book came out in the summer of 1997; by the Fall I had already made the determination to write my own [book]. However, it was a seemingly impossible task for a person who had only written articles. During the Yari Yari conference, which poet Jayne Cortez had a big hand in organizing, at NYU in the Fall of ’97, I ran into Amiri Baraka. We exchanged numbers, and in the back of my mind, I was hoping he would be of assistance, and he was, but in an unexpected way. Amiri gave me the number of [poet] Louis Reyes Rivera and one other person whose name I cannot recall. I had recently seen and heard Louis performing, so I was aware of his work and excited that he took on the task of assisting me [with A Strange Celestial Road].

I.E.: What was it about the Sun Ra experience in particular that compelled you to document so vividly that segment of your life & caree in this overall memoir sense?

When one looks at the fact that my sons were born just about the time I joined the Arkestra, and that I met my wife Monique Ngozi Nri while on tour with the band, or that my mother died while I was on tour, one gets to understand something about how my life has been so inextricably bound to that experience. And that’s not even looking at the music and the powerful effect that has had on my life.

Before you joined the Arkestra what was your overall impression of Sun Ra’s music and his philosophies, and what changed as a result of your up close & personal intimate experiences with the Arkestra and Sun Ra?

The first Sun Ra recording I heard that impacted me was Other Planes of There. This was a contemporary recording done in the 1960s as opposed to one I purchased at Slugs after hearing the band during their Monday night sets at that venue, called We Travel the Spaceways, which had been recorded around 1956. In A Strange Celestial Road I recount my dismay at taking the latter recording home only to find that it was not representative of what the band was playing when I heard them live [at Slugs]. Other Planes of There has a John Gilmore solo on one of Sun Ra’s originals, “Sketch”, which is still amazing to my ears, as is the composition. I was too young and inexperienced to play with the band then.

It would take me years of practicing and performing to get to the point where I was considered worthy, and some of the grooming came through working with a band known as the Melodic Art-Tet, which featured Charles Brackeen, Roger Blank, and Ronnie Boykins; the latter two had been members of the Arkestra. I got lots of second-hand information from the two of them before joining the Arkestra. No one could have prepared me for the discipline Sun Ra expected of one who joined the Arkestra. His rehearsals went on sometimes for hours. His commitment was totally to the music! The band was a learning experience because Sun Ra‘s life in the music went back to its beginnings in Swing and Ragtime, an we would play compositions he ha written out for us from those eras.

Some of the most compelling commentary in A Strange Celestial Road arrives after Sun Ra has ascended to ancestry amidst the various endeavors to keep his music alive and before the public. You talk quite vividly about such leader-posthumous legacy ensembles and band books as the Basie and Ellington bands and how those legacies have carried on to this day, and the challenges of your subsequent endeavors as a bandleader. In your work as an educator, were you to teach a course in how such legacies are kept alive and lessons learned from your experiences ultimately about bandleadership, what are some of the most important points you would stress to your students?

Leadership training is an important aspect of living and certainly my experiences with the Arkestra after Sun Ra left the plant confirmed how seriously training in that area is needed. My feeling is that in this country, there needs to be far more leadership training. In fact, both on the college level as well as in my elementary school music classes, I teach leadership, specifically using The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, written by Stephen Covey, as a source.

I like to call it the Seven Habits of Leadership because that’s more to the point. The 7 Habits asks and answers the question of how one develops the ability to work productively with other people to achieve lasting results. What one learns is that the first 3 habits: Be Proactive, Begin With the End in Mind, and Put First Things First, are designed to develop one’s independence. It is through the development of independence that one is able to make the leap towards working interdependently. Those habits of Think Win/Win, Seek First to Understand Then Be Understood, and Synergize are the blueprint for building lasting institutions.

When I left the Sun Ra Arkestra, I began writing my memoir at Sista’s Place [Brooklyn-based alternative performance space, green grocer, and Black political action hub] with Louis Reyes Rivera as my guide. [The late Sista’s Place catalyst] Viola Plummer asked me to be her Music Director in 1998 and for 25 years we worked together to build that historic landmark institution. Sista’s Place, unlike the Sun Ra Arkestra, and because of the leadership of Viola Plummer, was and is run by a functioning African centered collective called the December 12th Movement. It would take a few years for the Arkestra to get to that, post Sun Ra, but they got there. If you can find people who can move past ego into spirit, institutions that will last can be built and the 7 habits of leadership are a valued tool towards that end.

Have you taken some of the lessons you learned along the Strange Celestial Road to positively impact your career annd those of other musicians you encounter?

One of the things that we (Louis Reyes Rivera, Monique Ngozi Nri, and I) were able to do because Viola Plummer had the vision to build [Sista’s Place] and the understanding that Culture is a Weapon, was to create a thesis called Jazz: A Music of the Spirit. This is important because it means that generations from now., folks won’t have to reinvent the wheel or grapple with the question of how to name our art forms if they are diligent and heed the work we are leaving.

All of our art forms are “of the spirit,” of our African ancestors, we believe. We are. however, just dealing with the one I know best, which is the music people know as Jazz, with a capital “J”. In A Strange Celestial Road I break down how the word Jazz can be understood from a numerological perspective as being under the number 9. We have therefore identified 9 progenitors, The Divine Nine if you will, and they were all chosen because they represent principles that we believe are important and necessary to keep this music going and to build institutions with.

The progenitors are Duke Ellington, Mary Lou Williams, Sun Ra, Nina Simone, John Coltrane, Betty Carter, Jackie McLean, Abbey Lincoln (Aminata Moseka), and Yusef Lateef. The 9 principles we extracted are: 1) a transformative event has taken place in their life; 2) they have an advanced understanding of improvisation; 3) they understand the concepts of leadership and originality; 4) they are dedicated and devoted to a higher cause or higher power beyond themselves; 5) they understand music as a vocation and the need to teach it with passion; 6) they are activists on behalf of the communities from which they come; 7) they understand the principle of self-determination and ownership of the music; 8) they understand the need to build institutions supportive of artists who create Music of the Spirit; and 9) they understand the need to tie back to the African source of our art forms.

The thesis Jazz: A Music of the Spirit can be accessed online and there is an excerpt of it in the Acknowledgment section of A Strange Celestial Road. It is the basis for a functioning curriculum, which I have been teaching for several decades.

I.E.: Overall, what effect has writing and publishing A Strange Celestial Road had on your own career endeavors going forward?

The four years it took me to complete the manuscript were transformative. As I said, I had never attempted to do anything like this before, but Sun Ra‘s instruction to us, over the years, was that we had to do the impossible. Just as it is a seemingly impossible task that Marshall Allen, at nearly 100, could be leading the Arkestra and that he would start learning how to do it in his seventies, when I started writing this book, the idea of completing that project and getting it published was seemingly impossible.

Our goal on this planet, I believe, is to make the impossible possible. That’s the message Sun Ra left us with, and it is the reason that the institution known as the Sun Ra Arkestra is still standing after more than 70 years in existence. He would always instruct us that African people in America had a responsibility to stick together and there it is.

One of the immediate results of completing the manuscript was that I had to do some deep reflection. I had to note how much time and energy had been put into being an educator. Until I completed the manuscript, I really hadn’t considered the idea of being a full-time teacher but obviously I had logged so much time in that field it seemed a natural thing for me to go back to college to get the paper I needed to do it correctly. The next year after completing the book I was teaching a course on Sun Ra at the New School and eventually I would get to teaching music at an elementary school as well. So, I would say I was profoundly affected by the writing and the publishing of this book!