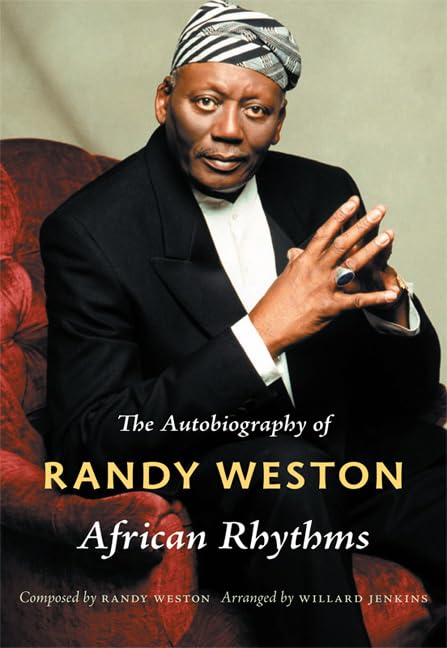

African Rhythms Chapter 10

Making a Home in Africa

© Willard Jenkins

“Son, never forget what you are. You’re an African. Though you were born here in the United States of America, you are an African. An African born in America, do you understand? Your mother country, the home of your ancestors, is Africa. Wherever you travel all over this planet, you must always come back to her. Africa is the past, the present and the future. Africa is the four cardinal points: the North, the South, where the sun rises and where it sets.”

— Frank Edward Weston as conveyed to his son Randy Weston

During the mid-late 1960s when I began to seriously contemplate making a life in Africa, considering my two earlier trips there Nigeria was naturally my first choice. It was an English-speaking country, so I figured there wouldn’t be a communication barrier; most of the educated people in Nigeria spoke English and I had gotten to know everybody from the Governor General to various Nigerians in television, radio, sculptors, painters and assorted other artists. Nigeria just seemed the most obvious African country for me to migrate to.

There were other possibilities on the continent as well. At that time, largely because of the successful independence movement there in ’59 and the charisma of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana was then the most celebrated African nation in New York. I had many Ghanaian friends at the time. But Nigeria still presented the most obvious migration possibilities to me since I had such positive experiences there, including friendships with Nigerian musicians like Fela Kuti and Bobby Benson, who owned the club Caban Bamboo there in Lagos. I had recorded Bobby’s tune “Niger Mambo,” so there were many reasons why Nigeria was the most obvious place in my mind. The Nigerians had really impressed me with the pride they had in their culture, and I was so impressed with the art there. It really is a fantastic country; the climate is great as well. But the Biafra war raging at that time was a real deterrent, so that took care of that and I never really came close to moving to Nigeria.

Besides my lifelong fascination with Africa, stemming first from my father’s teachings, there were some negative factors related to the music scene in the U.S. at the time which increased my desire to move to the continent. When the Beatles came on the Ed Sullivan show and I saw the hysterical reaction to their music, I saw everybody flipping out about that music, I said to myself: ‘oh man, black music in America is in trouble now. At the same time, the jazz scene in the mid-late 60s – at least as far as the press and the critics were concerned – was being heavily infiltrated with what they referred to as free or avant garde jazz.

What exactly is free jazz? For me the freest jazz I ever heard was Louis Armstrong. I never heard anybody play freer than him. The very concept of free can be intricate things, different kinds of things, which I have no problem with. But when it comes to free, with jazz, we must never lose touch with our ancestors, because every note, all that music we had been playing up to that point was really for freedom because we were under serious oppression between the slavery and the very powerful, mental and physical racism. So I had to ask myself ‘what are they talking about “free” jazz?’ It was like when they came up with what they called cool jazz, when Miles Davis came out with Gerry Mulligan and The Birth of the Cool and all of a sudden everybody was saying ‘be cool when you play, don’t sweat when you play… be like the Europeans in essence. But with us we sweat… so that didn’t really work for black musicians in general.

Then, after the Beatles hit, there was also all this critical euphoria over what they were calling free or avant garde jazz – which when I heard it didn’t excite me in the least and seemed so opposite black music – coupled with other disturbing things I was witnessing, I really got turned off to the music scene in the U.S. and began turning more and more towards Africa and an African existence. One night I saw Max Roach’s band opposite Dave Brubeck’s Quartet at a club in New York, I was appalled at how the audience seemed to completely overlook Max’s mastery and went wild for Brubeck’s so-called cool sound. It struck me that the collective audience was losing its taste for black culture, for what makes our music unique, what makes the music black people produce that makes it different than other kinds of music; and I truly wanted to stay in that tradition. But in the U.S. we seemed to be drifting away from that.

Nobody wrote more great music than Ellington, and I don’t care what Duke played or wrote you always heard the blues underneath. He wrote for the Queen of England, he wrote for the Emperor of China, but you’d always hear the blues underneath. For me, that’s us, that’s what makes our music unique; and to be modern you don’t have to play free or play a lot of notes. Our masters proved that, look at Count Basie or Thelonious Monk. The music I was hearing at this time seemed to be getting away from our basic traditions. When we play for people it’s supposed to be a spiritual healing process. It can be done with Ben Webster playing “Body & Soul”; it could be Clifford Brown playing “I Remember April”

There’s a certain romance, a certain love in our music, a certain emotion despite all the adversity. When you hear Coltrane with Duke and they play “My Little Brown Book,” there’s a certain romance, and that’s what I wasn’t hearing in the music anymore. We were taught that to play jazz you gotta be able to play the blues, you gotta be able to play for a woman, to romance her. I felt that the music of that time in the 1960s was getting more and more like machines with the electronics and things. If you don’t have a pretty sound it just doesn’t reach the people. The music was getting more and more western, for me it was getting away from the so-called black tradition, that feeling. So those were some of the factors that sealed my desire to migrate to Africa, curiously at the same time and for many of the same reasons that some of my peers were pulling up stakes and moving to Europe. Ironically my migration point was not to be the more obvious West Africa, but North Africa.

One month after returning from Morocco after our 1964 tour stop there I got a letter from the USIS in Morocco saying the Moroccan people are completely crazy about your music and they want you to come back. Our final concert on that 1964 tour, after three months on the road in Africa, was in Morocco. During our performance Ed Blackwell took one of those classic drum solos that just drove the Moroccan people crazy. When I came back to New York after the tour I found that the Moroccan people had been writing letters that were sent to me from the USIS office in Rabat, saying they were still talking about our concert and they wanted me to come back. So Morocco chose me, I didn’t choose Morocco, I later figured out.

The Foreign Service

Of the

United States of America

May 11, 1967

Rabat, Morocco

Dear Randy,

It’s been nearly a month since you left Morocco, and the fans are still roaring.

…As you know, Radio Maroc broadcast the Agdal Theater performance… once. The fans are outraged! The DJ has received about 100 phone calls and letters asking for a second airing of the tape, including one letter from Marrakech in which a young listener literally threatened the DJ if he did not play again “this greatest moment in Moroccan jazz history.” The radio has decided to run the tape again.

But more than this, our office has been besieged with demands that you come back to Morocco June 22 for the USIS-sponsored “1967 Festival du Jazz” at the American Embassy gardens in Rabat.

When you were here, you mentioned the possibility of going to Beirut this summer for a private engagement. You also suggested you might be able to stop over in Morocco on your way.

Do you think you could arrange to be here June 22 for the Jazz Festival? You’d really make the show, and placate 2,500 wildly enthusiastic fans.

Again, the Weston sound at the Embassy gardens would be a real sensation. We’d love to see you back, and await your soonest reply.

Best regards,

Charles L. Bell

American Embassy

One thing led to another and by 1967 I was finally ready to make the move. At the time I was living in the apartment on 13th Street that I had gotten from Ramona Low and Adele Glasgow, Langston Hughes’ friends. I was able to transfer the lease on that apartment to Booker Ervin and his family. So I left everything in that apartment, my piano and all the furniture, I left it with Booker Ervin and his family. The only things I took with me to Morocco besides my clothes were my papers, books and music. And because I wanted them to experience life in Africa first hand I took my children, Pamela and Niles, to live with me there. And this was despite the fact that I didn’t really know anything about Moroccan culture. The vibrations and the spirits were just right, Morocco was calling.

When I arrived in Morocco in’67 I found there was such a great appreciation there for the music that I became involved with their culture almost immediately. They have such a diversity of music, from the Atlas Mountains to the Sahara Desert, so I was always looking for their traditions. There’s a tendency on the part of some folks to feel that Western culture, or the Americanization of things, is supreme. That might mean that a McDonalds becomes more important than the traditional cuisine, like the traditional Moroccan tagine (or stew) for example. Because the west has dominated the world they’ve also created a kind of musical colonialism in a way; you’ll find American pop music almost everywhere you go. The Moroccans were very protective of their musical traditions, and that really appealed to me, drew me deeper into their traditions.

When we first got to Morocco, after landing in Casablanca, we came straight to Rabat because that had been where that concert that was our last tour stop in ’67 had taken place and it was also where those many letters had come from the USIS office, so it seemed like a natural first stop. Besides that it’s the capital city of Morocco. We wound up staying in Rabat for one year and if it weren’t for one very important factor involving my kids I might still be there, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

The American ambassador at that time, based in Rabat, was a Greek American named Henry Tasca, and he was very much in tune with my music. There was also a brother stationed there who was one of the deputies at the U.S, embassy, a man named Bill Powell. Bill was interested in helping me find my way there, and in helping me to create a base for African music in Morocco; to eventually have bases, or cultural centers, in different parts of the African world where people could come and study the culture, learn about it, take pride in it, and encourage the young people to continue the culture. That was my major goal in coming there. So we stayed in Rabat because there were people there who were willing to help me with my projects. I didn’t know anybody in Casablanca, I had just met some people there, but Rabat was like the center. It’s not as large as Casablanca but it’s a very beautiful city.

Embassy of the

United States of America

July 18, 1968

Mr. Randy Weston

Villa no. 3

Route des Zaers, km 3.800

Rabat

Dear Randy:

Since your first performance in Morocco in 1967, I have followed your career with great interest and much admiration. I feel that you are making an important original contribution both in your research on African folk music and in your original compositions inspired by African themes and adapted from African rhythms. I have been particularly pleased with the enthusiastic reception which your compositions based upon Moroccan themes, such as the “Marrakech Blues,” have had in Morocco.

I am sure that the benefits which will be derived from your research work on African folk music will be of major significance. As you so very well understand, Africans must be helped to rediscover their own music. They must learn to value their folk music, as you value it, realizing that the music of no other civilization can rival African music in the complexity and subtlety of its rhythms. At the same time, your research will help Americans to understand more fully the great debt that American jazz, blues, and spirituals owe to African music. Inevitably, the result of your work can only draw the African and American continents closer together.

I feel that you are uniquely qualified to carry out this important work. Your great talent as a composer and as a jazz pianist, combined with the warmth of your own personality, have won you friends wherever you have gone. You have been of great assistance to the American mission in Rabat, and I hope you will be able to continue work in Morocco for many years to come.

With warmest best wishes,

Sincerely,

Henry J. Tasca

American Ambassador to Morocco

I met a man named Jahcen who owned a restaurant in Rabat called Jour Nuit (Night and Day), and he also owned a hotel right on the beach. When I came to Morocco after they had persistently asked me to come back, I went back with a trio, with Ed Blackwell on drums, Bill Wood on bass and myself. We played at the Hotel Rex and this guy Jahcen was very interested in the idea of opening up a club with me.

One thing I had observed from my travels in Africa was that many of the prominent musicians there, guys like Fela and Bobby Benson in Nigeria, owned their own clubs. This gave them a base of operations and the opportunity to present music and musicians they favored. I was really into the idea of owning my own club; little did I know then what a headache that can be. But back then I thought it would be a great idea because I wanted to have a place where I could present our culture, the way we approach music, the way we approach life. That’s why I stayed in Rabat that year. Jahcen and I spent about a year negotiating this club deal, but ultimately it never happened, for one reason or another.

We stayed in the Hotel Rex for three months, and then I had to get a house because I was able to arrange for my children Pam and Niles to come over and join me after getting my divorce and gaining custody. Plus Ed Blackwell and his wife and three children were with us and we needed the space. I met a chauffer for one of the Moroccan government ministers and he arranged for us to rent a house just outside Rabat. We all shared this house, Pamela, Niles, Bill Wood, Ed Blackwell and his wife and three little children, all in one house. It was a two-family Moroccan house and everybody had a bed.

Besides making plans to open up this club we had also arranged through a Moroccan organization called DIAFA and the Minister of Culture to do a tour with the sextet. Ultimately they couldn’t afford to bring the sextet so we went a few places as a trio. We performed in Rabat, Casablanca, Zagora, and Marrakech, on about a 3-week tour of Morocco. The Americans wanted to contact the other places we had performed in Africa for return engagements because we were a big success on that 1967 tour and America always needs that good image through art and culture, so we were ideal; we were African American, nobody was a drunk, and we were always on time. We did a little playing here and a little there, but the main gigs didn’t happen so the tour idea fizzled out. As usual with musicians there were many plans for the next gig, but those next gigs were few and far between. And since I wanted to put my children in school and had learned that the best American school in the country was in Tangier, we moved there after that first year in Rabat. If it weren’t for that school I would have stayed in Rabat.

In retrospect it’s difficult to see how we sustained ourselves that first year. But the rents were very cheap at that time and our basic needs, like food and things were very inexpensive. And like I said, I arrived in Morocco with a little money because I was determined to live in Africa, so I had a little backup.

Tangier is right across the Mediterranean Sea from Spain and it is very near Portugal, so it’s a real international city. I met a lot of so-called expatriates hanging out in Tangier, people like the writers Allen Ginzberg, Paul Bowles, Brion Gysin, and others, who all appeared to be looking for something, I don’t know what. But they all lived in Tangier at the time, which made it even more of an international city. Besides that they seemed genuinely interested in having someone like me coming from the states there, a so-called jazz musician.

When we first arrived in Tangier I arranged to move into an apartment that had about four rooms, so both the kids and I had our own rooms. In Rabat I had a Moroccan woman named Khadija who did all the cooking and cleaning in our house and I was able to bring her with us to Tangier for a short time. Eventually we were able to rent a big house right on the beach through an American guy who must have been about 80 years old and had been living in Morocco a long time. It was a nice place with three terraces facing the Mediterranean. I hired a Jillalah chieftess named Haemo to be the cook of the house and take care of us. The Jillalah are like the Gnawa, another Moroccan spiritual sect, but I’m jumping ahead of myself. She was very strong and a superb cook. Each morning she’d go to the market and buy fresh food for that day. We lived in that house for over two years, with no telephone.

At the time I was going with a French woman named Genevieve McMillan who had some money from investments and was totally into African art. She and I talked with this old guy and rented this great house. These days Genevieve has one of the biggest African art collections in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She lends things out to museums all over the world. We got along well but in the end she didn’t get along with my children so she had to go. She gave me an ultimatum: ‘it’s either me or them,’ that kind of thing, so I said ‘bye.’ We split and left the house to her. The kids and I wound up moving to a small apartment, then to another very nice apartment on Boulevard de Paris. It was in a pretty modern apartment house, with four rooms, very spacious, lots of sunshine.

The American school was my major motivation for moving to Tangier, it wasn’t like I had been promised any gigs there. We did manage to play a couple of concerts, played a gig for the Hot Club of France in the city of Meknes, played at a couple of hotels and that kind of thing. Many people I met in Tangier were deeply into the arts and culture and there was a lot of talk about opening a jazz club in town, but for me it was just a challenge finding a useful piano, much less the commitment to act on such plans. The first year there I didn’t make any real money.

I felt like I was on a scouting trip because I wasn’t able to do very much playing. In ’67 I became friendly with a guy from the USIS office in Tangier, a very nice guy who was a writer. We tried to hook up a tour of Africa through the USIS but it fell apart at the last minute. At that time the USIS really knew the value of culture and they would send musicians to South America, Africa, etc.

Wherever I go on the globe I’m always interested in connecting with, or at least hearing, traditional music and musicians, and Morocco was no exception. The first of the Moroccan spiritual brotherhoods I connected with was the Jillalah, who I met through my friend Absalom, who was a government police official at the time and who loved the music. I met him in a bar through a woman from Vienna, Austria. Her name was Trudy and she had her own club where they would play Viennese waltzes and sing. He immediately said ‘man, I’ve got your record “Uhuru Afrika.” I was shocked! He invited me to his house and I met his gorgeous wife Khadijah who could really cook; I had my first home cooked dinner in Tangier at their house.

From that point on Absalom and I were partners, we became one with his family. He’s the one responsible for introducing me to the Jillalah, he and a Moroccan named Muhammad Zane. This was about the time I was just getting that house and they introduced me to Haemo, the Jillalah woman I hired to take care of the house. She was a strong Riff Mountain Berber woman; there was nothing glamorous about her. So because of her there would often be Jillalah musicians at the house. Jillalah is a Sufi sect; they see their instrument as a direct communication with Allah. They play these end-blown flutes called a qsbah or gisbah, and drums called bendir, that’s their way of communicating with the Creator.

There actually were three spiritual Moroccan musical traditions I connected with. Another was the Joujouka, who Ornette Coleman later connected with and made a record. The Swiss writer Brion Gysin was part of that European and American writers circle in Tangier, along with Paul Bowles and those guys. Brion was very much into the music. Through him I heard about this village in the Riff Mountains called Joujouka. By this time in ‘67 everybody I was in contact with knew of my interests in connecting with the traditional musicians. Mel O’Connell would arrange for government cars to take us to particular villages to hear the music, so we all went to Joujouka together.

For the trip to Joujouka you drive to a certain point where the mountain starts to rise and cars cannot go, so you either go by donkey or you walk. Joujouka is a village that has no electricity; it’s really soul Morocco with a beautiful view of the surrounding mountains. The Joujouka musicians are healers, they play a double reed instrument called the ghaita, kind of like an oboe, and they play those frame drums called bendir. They worship the god Pan, the god of flute. They have certain ceremonies where they prepare for three days or more. One of their mystics dresses in goat skin; they create huge bonfires and play their own Joujouka rhythms. People go into trance and jump through the fire, and they also have a special room where they treat people for various illnesses by using that cold mountain water accompanied by certain sounds they get out of their instruments. I’ve never had that experience so I can’t tell you what happens, but the Joujouka are reputed to be great healers. We spent three wonderful days with the Joujouka, enjoying the ceremony, the music, the dance, we ate fresh eggs, completely fresh food, the cooking was wonderful and I thoroughly enjoyed being with the Joujouka. But the Moroccan spiritual people I connected most deeply with was the Gnawa.

© Willard Jenkins