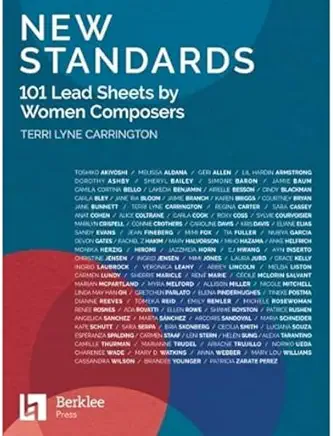

When drummer-composer-bandleader-educator-activist NEA Jazz Master Terri Lyne Carrington set out to right a historic wrong – i.e. the sad and ongoing lack of recognition for women’s compositions as vehicles of jazz expressions, she craftily went about assembling a vehicle for the broader dissemination jazz compositions by women. And in so doing she offers a document that will hopefully dispel any lingering myths about the compositional prowess of women operating in the jazz composing realm. In part New Standards serves as a touchstone volume for her groundbreaking Jazz & Gender Justice program and curriculum at Berklee College of Music. But more than anything her New Standards book is a marvelous illustration of the many important gifts to jazz contributed by women in the composers.

Not only has Ms. Carrington built a remarkable pedagogical standard at one of the planet’s leading music conservatories, she has also crafted an impressive platform for recognition and performance of a body of compositions that previously were only available somewhat anecdotally. Players know some of these compositions, but the anthology aspect represented by this New Standards volume is precedent-setting in bringing these compositional resources together, and will hopefully spur increased visibility for the extraordinary coterie of women composers, and vehicles for performance New Standards represents.

In addition to New Standards, Terri Lyne also curated a unique companion, a traveling visual arts exhibition that further illustrates the indelible role of women musicians in the development of jazz music – representing a range from Mary Lou Williams, Melba Liston and Geri Allen, to Carmen Lundy, Esperanza Spalding, and Kris Davis. Incorporating sculpture (including the memorable artistry of Ms. Lundy), a Geri Allen/Mary Lou Williams conversation, representations of many contemporary jazz women such as trumpeter-educator Ingrid Jensen (including a wonderfully illustrative photo of trumpeter Jensen practicing while holding her young child in her lap; a humane family/artistry juggling act many jazz women through the ages have encountered), bassist Linda May Han Oh, saxophonist-vocalist Camille Thurman, guitar explorer Mary Halvorson, and the emerging flutist-vocalist Elena Pinderhughes among them, and a Carrie Mae Weems film on Ms. Carrington that celebrates her amazing odyssey from 10-year old drumming prodigy (seeing the assured confidence of her posture at the kit at that young age is truly remarkable), to NEA Jazz Master and one of the essential contributors to jazz in the 21st century.

Clearly some questions were in order for Ms. Carrington and her Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice colleague Aja Burrell Wood weighed in with some wisdom as well.

While the New Standards book is so necessary and such a great companion piece to your overall mission at the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice, please detail how you determined to develop this volume.

TLC: The first event we held to announce the institute was in summer of 2018. I asked students to play some songs written by women at the event and when they pulled out the Real Book, they could not find any, other than “Willow Weep for Me” – by Ann Ronell. I knew then that this would be our first initiative. It took a few years to really get going with it. But when we met with Berklee Press (whose books are distributed by Hal Leonard), they told me 100 songs was a lot and they would still do the book if it were only 20 songs. And then asked if there are enough [women] composers to fill my ambitious request. It is actually 101 [compositions by women] because of an overlap or miscalculation when accounting for who said yes!

Once you developed your publication plan, how did you go about soliciting such a broad range of compositions by women across generations?

I started with people I knew – songs I had played before and songs I liked. It was fairly easy to do half the book that way. But in general I asked composers to send me a few songs to choose from – or I would tell them which song of theirs I wanted to include. Or a few people I would take anything they sent. With the deceased composers it was trickier because I had to deal with their estates and with some [composers] we could not really locate the people that controlled the songs – so we did not include a few that I wanted to. But it was always my desire to have it span over many years from Lil Hardin [who became Lil Hardin Armstrong] to top recent Berklee grads. And also to be diverse stylistically within jazz.

What was the response from the field when you began soliciting these compositions?

Everyone was happy to be included. I only got 2 rejections.

Was the goal to publish exactly “101 Lead Sheets by Women Composers” or is that simply the number you wound up attracting?

The goal was 100 – but it ended up at 101.

How do you see this book proliferating in the field, and particularly among musicians?

I see it as an addition to the jazz canon of songs that we all play all the time – that rarely includes women composers. So New Standards is saying, “If you want to be more diverse with the composers you play, here are some other options.” Many musicians mainly play their own music, but while they are developing their craft and their writing skills – in school – they play other composers, and the way it has been, male composers are the ones who are informing our budding composers and performers, which reinforces the male jazz narrative. But now there is something that can be used to counter that narrative, if an educator (or performer) wants to do so – neatly, packaged in a collection, which means there is no excuse if you want to diversify the material being taught, because a lot of people say that they could not easily find music written by women. Not so anymore.

The New Standards traveling exhibition premiered at The Carr Center in Detroit, where Ms. Carrington is a curator, and subsequently touched down at the home of the DC Jazz Festival at Arena Stage in DC’s southwest waterfront corridor (home also to DCJF festival stages at The Wharf and Arena Stage) during DCJF 2024.

Talk about how you arrived at the exhibit as such a vivid and illustrative companion piece to the New Standards book and what do you foresee as the future of the exhibit?

I have always been attracted to multi-disciplinary expression. If you are a creative person, chances are you are creative in more than one area. It could be said that men have had it easier with their creativity being both accepted and expected – no matter the form it is being expressed in. They have been supported – often by women – to go be a “creative genius.” but women have had more barriers and burdens pursuing their creative endeavors and for sure more glass ceilings. The exhibit is a [vehicle] to center multi- dimensional, multi-disciplinary artists in, a space dedicated to the varying contributions women have made and continue to make in the art form, from different parts of the jazz ecosystem.

Bringing ideas of freedom and jazz without patriarchy into a space with sound (pressure waves), 2D (film) and 3D (paintings, sculptures) art. And the exhibit’s purpose was also to overwhelm you with the theme/topic. It was my hope that after visiting the exhibit, the viewer would be transformed, inspired and educated in some ways as well. And at the very least, not able to say that they did not know there were so many great jazz women performers and composers. The hope is for them to leave looking at jazz differently, acknowledging that jazz has a gender problem, realizing their own part – knowingly or not – in supporting the inequities, and resolved to pay better attention to how and what they support in reg

ard to the art form. A resolve to being part of a solution and change – not part of keeping jazz from reaching its greatest potential, which can only happen when there is diversity among the people that create it. Jazz is not men’s music – and that is what the exhibit is saying loudly.

Aja Burrell:

Terri covered it all. I would add to your question about proliferation… since New Standards has become available, I believe it continues to have the potential to add to and reframe what we consider the “standard” in jazz on and off the stage, and in classrooms near and far.

An immediate impact I have already witnessed (and heard) has been the way the tunes in [New Standards] have been incorporated in curriculum, in jazz education spaces, and live performances. And in such a short time! On Berklee’s campus alone, I can’t count how many times I’ve heard Geri Allen’s “Unconditional Love” coming out of practice rooms at times simply because the students love to play it. Let alone, the enthusiastic response from both students and educators I encounter from other institutions, who are now incorporating New Standards tunes in their sets and beyond the classroom.

The response to New Standards has been tremendous and the proof has been in the music. I look forward to seeing its continued impact over time.