Back in the early 80s, when hip hop was in its nascent stage, a young man who grew up in Brooklyn – definitely one of the root beds of the form – named Fred Brathwaite, Jr. was making his moves on that cutting edge. Originally an aspiring graffitti artist, young Fred immersed himself in those early experiments, basment-rapping with an aspiring DJ friend in the rawest sense of what became hip hop.

According to Freddy Brathwaite’s Wikipedia entry: “As a teen in the 70s he was a member of the Brooklyn-based graffiti group The Fabulous 5. He got his name for consistent graffiti “bombing” of the number 5 train on the IRT [subway line]. In the late 1970s and early 1980s he was an unofficial bridge between the uptown graffiti and early rap scene and the downtown art and punk music scenes.”

Eventually Freddy Brathwaite made some pioneering moves that elevated what was originally designated rap music, then morphed into a global form of its own known as hip hop. But long before that he’d come under the spell of jazz music, a form which was never far below the surface of his music consciousness as rap music was blossoming and coming into its own.

Freddy grew up in Brooklyn’s fabled Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in a household where jazz music was king. And besides the influence of jazz platters constantly spinning on his mom and dad’s turntable and wafting out of home radios, young Fred’s godfather was none other than than the great drum pioneer Max Roach.

During the course of our many interviews for his autobiography African Rhythms on his growing up in Brooklyn and all the people who influenced him in the borough – musicians and lay people alike – Randy Weston often spoke of Freddy’s dad, Fred Brathwaite, Sr., Max Roach, sculptor Jimmy Gittins, and jazz enthusiast-photographer Jimmy Morton. And Randy mentioned on several occasions that one of the younger keepers of that legacy, one who had collected many of Jimmy Morton’s Brooklyn jazzlore photographs, and one who as a youngster had really paid attention to the influence of jazz music around his home and neighborhood was, as Weston characterized him “the rapper, Fab 5 Freddy.”

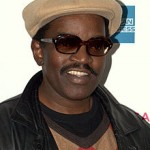

About 18 months ago when I was blessed by the Weeksville Heritage Center with the opportunity to conduct oral history interviews with Brooklynites – interviews which for The Independent Ear have yielded priceless insights into such Brooklyn venues as the East and the current successor Sista’s Place (scroll through the archives contents) – interviews largely focused on the borough’s rich tradition of jazz venues, clearly I had to catch up with Fab 5 Freddy. What follows is part one of excerpts from our interview with the loquacious brother with a keen memory. One gorgeous fall afternoon we caught up with Fab at his Lower Manhattan studio.

Willard Jenkins: Since your father was so heavily involved in jazz, what’s your earliest recollections of jazz music?

Fab 5 Freddy: My earliest recollections were [of] jazz being played all the time in the house, along with fiery discussions about everything affecting us as a people. I’ve got vivid memories of jazz being played in the house going way, way back. The jazz station that I can recall was WRVR with Ed Beach, who was a hipster with a massive collection of the music. I remember as a young kid wondering how they could know who a guy was just by the instrument that was playing! I would later learn to do that myself.

My dad and Max Roach were friends from teen years at [Brookyn] Boys High School. Max played in drum & bugle corps as a kid and then he became this young whiz kid drummer playing with big bands. He quickly rose in the 40s to be one of the architects, and my dad was right along with him. There was a group of friends who had formed a social group that referred to itself as The Chessmen; they developed a love of chess during World War ll.

Max lived in a big, kind of old mansion at 212 Gates Avenue. This house, I understand, had a huge living room and a huge baby grand piano and they would have these sets. As Max became prominent he would bring other Brooklyn jazz guys to come and hang with my dad and his friends. Hence that became a scene of jazz hipsters and frontrunners in Brooklyn.

(Editor’s note: Read about those days from Randy Weston’s perspective in Chapters 2 and 4 in African Rhythms, and also in Robin D.G. Kelley’s extraordinary Thelonious Monk bio An American Original, about Monk’s days performing in Brooklyn when loss of his cabaret card prohibited his playing Manhattan clubs.)

Was it your sense that this group of guys, the Chessmen, was hanging in clubs in Brooklyn?

Fab: Yeah… There was the Putnam Central, which I heard a lot about. Along with having these gatherings – sets as they called them – at the house on Gates Avenue there was a period of time where my dad and his friends were promoting their own [jazz performances] at this place called Tony’s Grand Dean, which was on Grand and Dean Streets in Brooklyn. I’ve got a series of photos [from Jimmy Morton’s collection] which I let Robin Kelley use for his Thelonious Monk book which document that scene.

The interesting thing about these pictures [displays one with Monk, Mingus, Miles, and Max on the bandstand in Brooklyn] – [they were] in color, one of the first 35mm slide cameras, the beginning of that technology, and Jimmy Morton had one. Its very rare to see color shots of jazz guys from the early 50s, everything is always in black & white. These slides that Jimmy has given me over the last 20 years document this scene. I’ve heard stories about countless times when the vibe would hit the right pitch at our house and the music was right, my dad and his friends would always go back to things that happened at Tony’s. It was always exciting to hear these guys get real geeked up talking about what happened and I would often be a little kid playing in the room with my toys and things, but would tune in to these stories.

During a critical period for Monk when they had taken away his cabaret license, which as you know was his ability and legal right to play in clubs… he couldn’t feed his family. So these particular gigs [primarily at Tony’s] were gigs that helped keep Monk alive. Robin even found a little ad in the Amsterdam News archives of one of those gigs at Tony’s that Jimmy Morton blew up and I framed.

You talked about those sessions the Chessmen used to have at Max’s house on Gates Avenue; what were they like?

Fab: That was more like jam sessions. The musicians would come and play and it was just like a scene. The thing that was infectious to me was the enthusiasm and the energy they would have when they would get into those conversations. Jimmy Gittins, who I would say was such a huge influence on me and what I even do now, was like a big brother/uncle to me. It was Jimmy Gittins, Lefty Morris, my dad, and [drummer] Willie Jones. Willie was always there, and Willie was an activist. He was at my house three days of every week until I was an early teenager; he was like a fixture at my house, along with at least three other [jazz] guys.

At what point did you become more conscious of what they were about?

Fab: I was always conscious; as a little boy I was aware of these things and I would hear these tapes, but I was pretty much still a kid playng with army men and stuff that kids would do. I’m a kid with all my issues being taken care of by my parents, so I didn’t get to experience what they knew as black men you had to experience at that time. Especially when musicians went on the road and how they had to live, the situations these young, intelligent men were forced to deal with when they went out into these different environments and were very actively concerned with making change. I’m saying all that to say that I also realized later in life that my dad was a big part of Max [Roach]’s consciousness and awareness at that time.

How so?

Fab: You hear it in [Max’s] music. It was all further explained o me when I grew up and as an adult Max would explain things to me himself. One of my earliest remembrances of a Max Roach record is the “Freedom Now” suite, “We Insist” – that record. One of those records has a photo on the cover of Max and some men sitting at a lunch counter, and as a very small boy I always wanted to know what this was about. My dad and them would explain this to me. I destroyed a lot of my parents’ records as a kid playing with them, but the images on those records… there was great photography at that time, abstract art, etc. I would later see records and I’d be like “Oh my God’!…

My mother had all the jazz singers – Sarah Vaughan, Nancy Wilson, etc., ec. and my dad had a nice collection of a lot of the bebop records and they would listen to them both. But my mother was always into the singers. My mother hung out a little bit with Dinah Washington, she hung out a little bit with Etta Jones, and I remember the imagery from those records. So if I see them now I’m like “Oh my God, I’ve seen this, I know this…”

I have a little collection of photos and I think I was developing my visual sense at that time through looking at and playing with these records, but particularly the “Freedom Now” suite. As I grew up and got to understand a little bit more about Max I realized that was one of the first protest records; the beginning of the 60s, the beginning of anti-war protests, the whole cultural revoltution that transpired at that time. I realize that Max was at the forefront, and my dad’s influence [was important], because when they came to my house my dad pretty much held court. He had read the complete works of Mao, Marx, and Lenin – all this stuff.

When you say that your dad had an influence on Max Roach as far as his political consciousness, explain that.

Fab: My dad had read all the works of Mao, Marx, Lenin and also African nationalists; my dad wanted my middle name to be Lumumba but my mother wasn’t going for it [laughs]. But later I learned who Lumumba was and how incredible these guys were and how a lot of my dad’s ideas were right in terms of alternatives that were much more viable – whether they worked or not in other countries – 30 or 40 yeas later we can see that those things didn’t pan out as well as they were sketched out in those books… But that’s what went on at my house. These guys would roll up and do their thing, listen to music, and have these intense discussions and debates. Often my dad would have the most insight because he had read the most and had this kind of broader understanding of what was going on in Africa, what was going on in China… as all these African countries were getting their independence.

What’s your recollection of how the music interacted and spurred some of that discussion, because the music was obviously more than a soundtrack for those discussions?

Fab: Yes, absolutely! My dad’s den/study was in the basement where the real shit would go down. Thelonious Monk… as I’m growing and becoming a young teen I’m beginning to now discern who the musicians are that I like, that I’ve been hearing forever and ever. Monk becomes that musician; I became fascinated about this whole thing with Thelonious. One day I looked in my father’s phone book and I saw Thelonious’ phone number, and I call his house and I speak to Nellie [Monk, Thelonious’ wife].

How old were you at the time?

Fab: Twelve, maybe a little younger. Remember, I’m still kinda little boyish because when I look back to that I think ‘God, that’s such a kid thing to do!’ She could tell it was a little boy calling and I said ‘hi, I’m Freddy Brathwaite’s son and I want to talk to Monk, I know my dad knows you.’ She was really sweet and I started talking to her and I guess I was telling her that Monk was a musician that I really liked and in the course of discussing that she said, “you know Freddie, jazz is like a conversation, and in the beginning of the conversation somebody makes a point and then they go on to explain that point.”

I’d been listening to this music all the time and from that I now get what’s going on: the song starts off, the theme is stated, and then these guys all go off and do their own interpretation and you could still hear the theme going through there, like that’s the point. And I get it now, this became really apparent to me and I was like ‘wow, yes…’ and now when I’m hearing songs I could understand them and see how different guys do their thing as they get into the improvisation and all that stuff. But I guess I also began to understand that the guys making this music were really intelligent and they were really aware of their times, so the music was a reflection of this, therefore the music was an articulation of the intelligence and point of view of these very sophisticated and modern musicians.

I knew that Max and my dad were in synch with a lot of the same thoughts, and then once I got older I figured out a lot of these things for myself. You just realize that these are very intelligent men and they’re very concerned. I’m not trying to say that all jazz music had this protest, let’s make revolution thing but it clearly was an affirmation of us as these modern individuals, which I guess is the thing that had the most impact on me because I always saw them in that light. Those conversations that went on, I realize that these particular individuals had a lot of conversations like this.

I remember later, when I became a young man and spent a lot of time with Max and things that we would do together. I remember Max telling me how when Olatunji first came over [from Nigeria] how him and Dizzy were so excited about this new thing going on. And I remember Max explaining this to me because Max was a very big, early supporter of me being involved in hip hop music and culture. So Max essentially instigated us having gigs together.

STAY TUNED TO THE INDEPENDENT EAR: IN PART TWO FAB HIPS MAX ROACH TO HIP HOP’S INCUBATOR STAGE AND THEY FORGE A COLLABORATION.

Pingback: Around The Jazz Internet « Meme Phi!omath