Despite the crispy weather chill, early January is a vibrant time to be in New York; it’s arts conference time in the City. The fulcrum is the annual Association of Performing Arts Presenters, or APAP Conference at the midtown Hilton Hotel. With thousands of arts presenters, from small community presenters to big boys like the Kennedy Center, as well as arts funding organizations ascending upon the city at conference time – including the Chamber Music America conference and its ongoing embrace of jazz as a chamber music – artists and artist managements scramble to present all manner of new works, complimentary concerts, clue dates, and showcase performances at spaces and pop-ups around town. For those of us in the performing arts, despite the customary January weather challenges, the first weeks after the holidays are a great time to be in the City.

Several years ago, in response to APAP conversations and encouragements surrounding jazz music, the Jazz Connect conference was developed; held at St. Peter’s church, long known as the “jazz church” stemming from its traditional jazz vespers service and the developments of the late Rev. John Gensel, including hosting many jazz masters homegoing services. One of the principle partners in the Jazz Connect schematic was JazzTimes magazine, which as many know once hosted its own Jazz Times Conventions, which were eventually embraced as the jazz industry tract sector of the huge former International Association of Jazz Education (IAJE) conferences. From the ashes of IAJE’s ignominious downfall has arisen the Jazz Education Network conferences, also held in January but presented in a different region each year, much in the manner of the former National Association of Jazz Educators conferences, before the organization’s ill-fated decision to go International. Unlike its predecessor IAJE, JEN (whose 2018 conference was January 3-6 in Dallas) has determined to concentrate on the jazz education field, which left the other sectors of the jazz community (working musicians, radio, records, journalists & publications, managements, jazz presenters, clubs, etc.) to the Jazz Connect conference. Conference dizzy yet? There’s more…

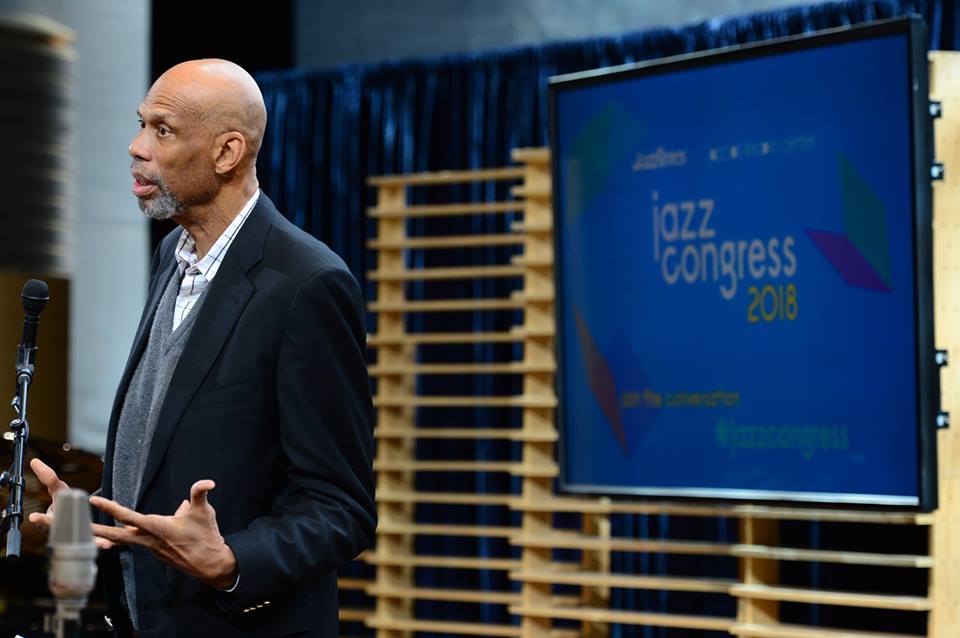

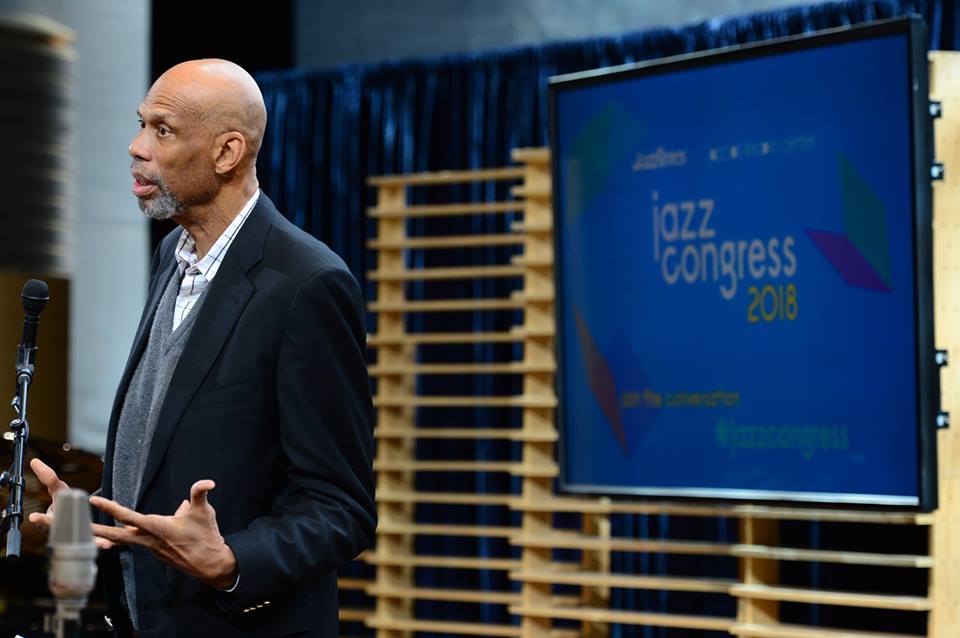

For this year JazzTimes partnered with the Jazz at Lincoln Center organization to morph Jazz Connect into the Jazz Congress, hosted at JALC’s immaculate facilities in Columbus Circle. Panel discussions and professional development sessions, as well as college and university jazz ensemble performances in the Atrium, commenced Thursday, January 11th and Friday, January 12th. The keynote address was potently delivered by NBA legend and lifelong jazz enthusiast Kareem Abdul Jabbar.

Among the sessions this writer sampled that delivered real sustenance were Jazz and Race: A Conversation with Wynton Marsalisand pianist Ethan Iverson, moderated by artist manager Andre Guess. Gender and Jazz, moderated by journalist Michelle Mercer, was a particularly timely exchange in light of the #MeToo and subsequent nationwide allegations of sexual harassment making headlines. The discussion highlighted both well-documented and what for some may be the less-documented challenges faced by women jazz artists. Particularly poignant testimony was offered by trumpeter Ingrid Jensen, drummer Terri Lyne Carrington (Bruce Lundvall Visionary Award-winner), and bandleader Ellen Seeling. At the Learning from Large Jazz Organizations I posed a question to SF Jazz Organization founder Randall Kline about the challenges of wearing his artistic hat along with now being in the real estate business courtesy of their exemplary headquarters/performance space.

L to R: Ethan Iverson, moderator Andre Guess, and Wynton Marsalis discuss Jazz and Race matters

L to R: Gene Dobbs Bradford (Jazz St. Louis), Randall Kline (SF Jazz Center), Amy Niles (WBGO) expounding on the life of a large jazz organization

What Does New Orleans Mean Today? was passionately moderated by journalist Larry Blumenfeld, who like me shares the peculiar “ownership” of the essential prominence of that great city shared by those of us who’ve lived there for even the minute that Larry and I coincidentally shared in ’07/’08. Given the questionable approach to jazz performance of certain younger musicians where it concerns stage deportment, the session “Why performance matters: stagecraft masterclass” ought to be repeated at jazz education programs and conservatories as a vital curricular addition.

Drummer-educator Ralph Peterson dropping science on a participant in Jazz Congress’ Ask the Experts roundtable; think speed dating for jazz consultations

Perhaps the warmest, most engaging session of all was the “Jazz legends roundtable”, which brought together three stellar jazz master pianists: Kenny Barron, Joanne Brackeen, and Harold Mabern for a wonderful bit of reminiscence. Hearing Joanne Brackeen recount how she pretty much stumbled upon her opportunity to become the first and only female member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers was priceless, as was the wit and wisdom of Mabern and the erudite Kenny Barron. Though there was a piano standing by, the three masters had no intention of playing – at least not until an audience member asked if they’d grace us with some playing, which solicited beautiful interludes from the trio of practitioners.

Elsewhere there was a Jukebox Jury with jazz radio programmers listening to tracks and being quizzed on whether the selected music stood a chance of making their respective playlists; a session on Jazz in film and TV soundtracks, Building partnerships in secondary markets, The power of crowd funding, Audience development: casting a wider net, New models for jazz education, Jazz vocalists and repertoire, and The artist-manager relationship, among the four rooms of simultaneous sessions running from 9:30am-evening each day.

Despite obvious rewards for the open-minded to be garnered from attending various sessions, the truest value of a conference like Jazz Congress is connecting with others in the business, including various reunions of folks who only see each other annually, catching up with old friends and meeting new, and being introduced to some of the more useful trends in the jazz industry, and particularly in this case, sampling the incredible mosaic of live music offerings across Manhattan that week. That’s the foundational platform of such annual confabs – just as it is in other business pursuits.

The scene at Jazz Congress conference registration

Of equal value is being in New York City for that sumptuous fortnight amidst a veritable flood of tantalizing performance opportunities large and small. Thursday evening after the concert proceedings yielded an amazing set by pianist-visionary Vijay Iyer‘s Sextet at Birdland. Powered by the commanding traps of the much-discussed Tyshawn Sorey, with a remarkable frontline of saxophonists Mark Shim and Steve Lehman, and cornetist Graham Haynes, and bassist Stephan Crump anchoring the bottom, Iyer pilots one of the most deeply engrossing ensembles in modern music, which largely gave wing to the originals on Vijay’s current ECM release, Far From Over.

Chief grocer responsible for that week’s overflowing shopping cart full of goodies is the annual Winter Jazzfest. Running this year from January 10-17, Winter Jazzfest was originally developed in response to the city’s annual influx of performing arts presenters swarming the APAP conference from across the globe. From a jazz perspective that swarm includes the European jazz festival presenter collective and the Western Jazz Presenters, each group in town for their annual meetings to discuss block booking, special project opportunities, and shared presenting perspectives. With all that in mind, presenting the fertile marketplace that is the Winter Jazzfest during the second week in January makes perfect sense.

Founded and produced by the gifted and politically woke Brice Rosenbloom, Winter Jazzfest plays multiple downtown spaces, including clubs, a hotel, and several spaces at the New School, as well as one evening at Town Hall in midtown. The Friday and Saturday evenings of WJF are designated as festival marathons, with simultaneous performances cooking in all of the festival venues. Not for the faint of heart, the temptation for the adventurous is to map out a strategy to catch as many performances as the shoe leather will allow over the course of the two evenings, which begin as early as 5:30 and cap with 1:00am sets.

After a couple of years endeavoring to make as many tantalizing sets at however many spaces that strategy required, discretion yielded the better part of valor. That measure of prudence required a careful scan of the WJF schedule to determine which space offered the most tantalizing aggregate lineup, arriving early, scoping out good seats and basically camping out for the evening. And being a – ahem – seasoned jazz advocate, guaranteed seating is no small requirement; here it should be noted that depending upon arrival time and crowd shifting patterns, certain WJF spaces usually require standing – including one of the primary WJF venues, Le Poisson Rouge, where standing is the rule.

Of the three WJF evenings your correspondent caught, Wednesday, January 10th was the only one which braved seating disparities. But after awhile standing up on creaky knees at Le Poisson Rouge for an evening billed as “Gilles Peterson Hosts British Jazz Showcase,” hosted by the noted UK record producer and re-mixer, I yielded to the call of The Baylor Project at the Jazz Showcase, where seating (and a good menu) is guaranteed. Disappointment at not catching the chief reason for visiting the challenging Le Poisson Rouge, the tantalizing saxophonist Nubya Garcia, aside, shifting to the Jazz Showcase proved a good move. Before the split, vocalist-guitarist Oscar Jerome showed evident skills, including some rapping propers, was followed by the spacey exploits of trumpeter-composer Yazz Ahmed to open the evening.

The Baylor Project proved an infectious, engaging alternative. Drummer/co-leader Marcus Baylor had impressed mightily at the traps driving Kenny Garrett at last June’s memorable DC JazzFest appearance. It was the vivacious vocal half of the project, Jean Baylor, who thoroughly captivated. Ms. Baylor, blessed with a full measure of the Holy Ghost in her vocal timbre, positively inhabits a song! Tenor man Keith Loftis was quite impressive, and as always trumpeter Freddie Hendrix blew heat and fleet of finger; going beyond namesake obviousness he’s an inheritor of a certain measure of the Freddie Hubbard mantle of audacious trumpeters. Given the Baylor Project’s soulful expressions, it’s not surprising that they’ve scored Grammy noms in both the jazz and contemporary R&B categories, despite the fact that theirs is no question a sensibility born out of the art of the improvisers.

The two most thoroughly tantalizing and essential evenings of WJF are their Friday and Saturday night marathons, with simultaneous sets at 11 venues, which for the intrepid seeking the lost chords requires both street map and accommodating kicks. As mentioned earlier, a few years ago I adopted a one venue/camping out for the evening mentality where it concerns these two marathons. As was the case last year, that meant the relatively comfortable confines of the New School’s Tishman Auditorium.

Friday evening also brought good friends Pat and (vocalist) Allan Harris‘ annual Harlem After Dark house party/artist showcase way uptown from WJF’s downtown haunts. After catching a few showcases it was Uber downtown to 5th Avenue and 13th Street for Tishman Aud. That meant missing Steve & Iqua Colson’s Music of Protest & Love (dedicated to Muhal Richard Abrams) and vibraphonist Stefon Harris‘ latest edition of Blackout, with Casey Benjamin, but that was made up for in part by catching a taste of Stefon’s latest muse at manager Karen Kennedy’s subsequent Sunday brunchtime showcase. Next up was guitarist Marc Ribot‘s Songs of Resistance, which could have benefited mightily by the engagement of a vocalist to handle Ribot’s deservedly snarky political screeds, which singled out #45 for some well deserved vinegar. But alas the guitarist-composer chose to handle the vocal chores himself, decidedly a bit less than satisfyingly – more howl than honey.

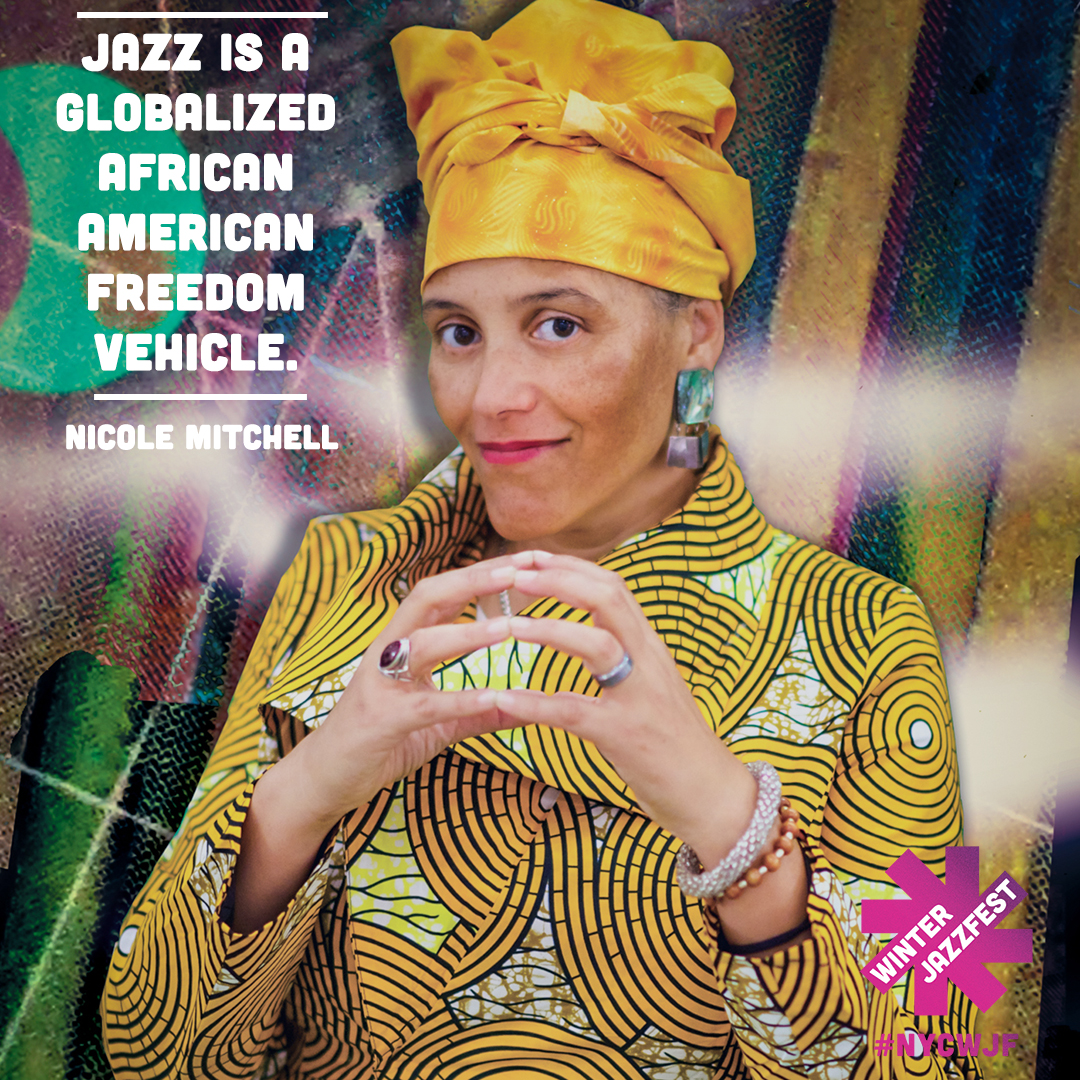

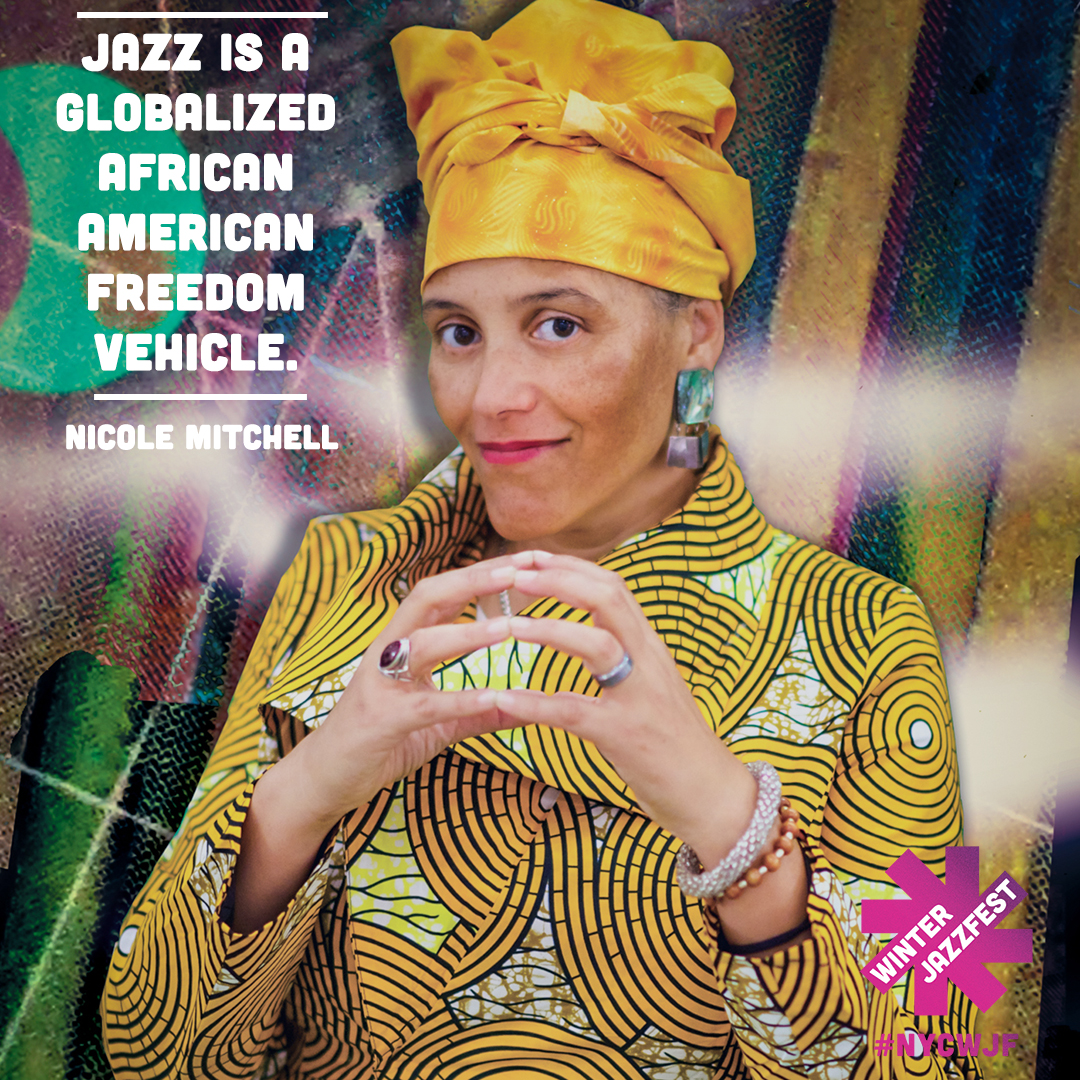

Flutist-composer Nicole Mitchell, this year’s WJF artist-in-residence, more than rewarded the lengthy trek downtown. She served up a compelling program wrapped in the poetic irony of the late, great Chicago laureate Gwendolyn Brooks. Two sisters served up Brooks’ prose amidst a succulent melange of Mitchell’s original music, which was bolstered by the ever-rewarding presence of Jason Moran at the piano. Few are serving up the 21st century flute with quite the panache and originality of Nicole Mitchell.

On Saturday afternoon the Jazz Journalists Association (JJA) presented its JJA Media Summit at the Jazz Gallery. What ensued were lively and often informative panel discussions before a good audience, including Women in Jazz Journalism, moderated by Michelle Mercer, followed by Black Lives Matter and other Social Justice Issues in Jazz Journalism was moderated by Don Palmer, where I served as a panelist. Rounding out the day was Beyond the Immediate: Photographers, Broadcasters on Extending Outreach, moderated by Howard Mandel. The other panelists and moderators (including some good friends) I knew from past interactions and encounters. I was delighted to meet Jordannah Elizabeth, a bright young sister writing on the music from Baltimore, who served on both the Women and social justice issues panel and brought fresh perspectives to the very worthwhile summit.

A view from inside the JJA Media Summit and the social justice issues panel L to R: moderator Don Palmer and panelists Larry Blumenfeld, Jordannah Elizabeth, Russ Musto, Willard Jenkins, and Greg Tate at the Jazz Gallery

Day 2 of the marathon delivered a healthier portion of the goods, ranging from impressive young vocalist Jazzmeia Horn‘s positive inhabitance of the Betty Carter legacy, to electrified saxophonist James Carter (think Eddie Harris on steroids)’s Electrik Outlet, and the trio Harriet Tubman’s Free Jazz deliverance. In the tradition of Ornette’s freedom principle, Tubman was joined by the flame throwing saxophonist James Brandon Lewis‘ trio, including DC’s own Luke Stewart doubling the bass quotient with Tubman skronkster Melvin Gibbs, and horn work from alto man Darius Jones and the increasingly-discussed young trumpeter Jamie Branch. To paraphrase writer A.B. Spellman, this performance completely cleared my sinuses of whatever congestion the week’s wintry chill might have brought on. If I had head hair, it might have stood on end from the ensuing musical maelstrom! The Sun Ra Arkestra closed the evening performing a live score to Ra’s film “Space Is The Place.” As has been customary with certain WJF evenings, this one brought back potent memories of trolling the downtown lofts in the 70s.

Sunday afternoon surrendered a raft of ultimately engrossing APAP showcases, including Stefon Harris’ aforementioned “informant” – his designation – related to the leader and some of his sidemen seated audience front speaking to his musical sensibilities – playing some, talking some and engaging the invited brunch audience at the Yamaha studio space. Shifting a few blocks westward to APAP’s HQ hotel, the Hilton, yielded the second of the enterprising Pat Harris’ annual showcase afternoons. Among other goodies, Pat served up the charming husband-wife led quartet of pianist-vocalist Svetlana Smirnova and drummer Oleg Butman, two new friends from the November trip to St. Petersburg, Russia for the inaugural Jazz Across Borders conference. Vocalists Brianna Thomas and Rochelle Rice brought their neatly contrasting, very gratifying vocal stylings and engaging delivery to the 4th floor showcase suite, whereupon Penn Station beckoned for the train ride back at the close of one of New York’s most performing arts engorged weeks of the year.