Besides being a truly great trumpet player, composer and bandleader – and one that too many folks sleep on from the historical lineage of the music – Woody Shaw was a very important figure in my earliest stages of concert presentation and production. That work began back in the late 1970s/early 1980s as president of the former Northeast Ohio Jazz Society.

During that period the late Bruce Lundvall took advantage of what was apparently some unusually broad corporate latitude to sign and subsequently record several of the most vital musicians on the scene, including NEA Jazz Masters Dexter Gordon and Bobby Hutcherson, and such other singular masters as the late alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe and trumpeter Woody Shaw. When Dexter Gordon made his triumphant return to the U.S. after years in European self-exile, he arrived full force at the Village Vanguard in a highly touted week that found him riding majestically on the wings of a deeply complimentary band that had been the working unit of Woody Shaw, which certainly eased Dexter’s way back on the U.S. scene in superb fashion. I contacted Maxine Gordon, who at the time was representing both Dexter and Woody, and what quickly followed were very successful performances by both on separate dates at Cuyahoga Community College Metro Auditorium as part of NOJS burgeoning concert series.

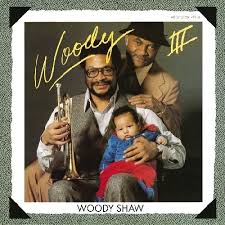

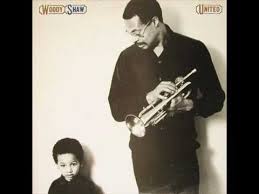

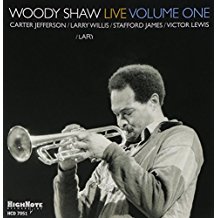

I had first become familiar with Woody’s recorded work a few years prior when my brother George hipped me to his extraordinary 2-LP set Blackstone Legacy and was immediately hooked by his surging, questing sound and singular approach to trumpet expression. Years later we commemorated Woody Shaw’s rich legacy in concert at Tribeca Performing Arts Center as part of our annual Lost Jazz Shrines concert series. It was then that I first came in contact with the very earnest son of Woody Shaw, Woody Shaw III (www.woodyshaw.com/woody-iii), who as an infant and a young boy had appeared on two of Woody’s subsequent album covers for Columbia. Fact is Woody Shaw was our last great and true trumpet stylist.

Since his father’s passing Woody III has been busy with his father’s legacy, which recently has included plans to produce a Woody Shaw documentary. Clearly some questions were in order for Woody Shaw III.

IE: You’ve come a long way from that WoodyIII album cover photo with your Dad and Grandad. Talk about your evolution in terms of your education and more recently your Harvard fellowship.

Woody Shaw III: Well, my educational background was in many ways shaped by a decision I made as a younger man, which was to acquire all of the tools necessary to interpret, organize, preserve and curate the legacies of my musical forefathers well into the future. And when I say my musical forefathers, I mean both my biological father Woody Shaw (1944-1989) and my step-father, Dexter Gordon (1923-1990).

Having grown up at the nexus of the artistic and the managerial domains of the jazz world [Woody lll’s mom the historian-educator Maxine Gordon managed both Woody and Dexter], it became apparent as I reached my early twenties that my future would require me to administer these legacies on a professional level, as well as to protect them from any foreseeably egregious forms of legal or economic exploitation, indefinitely. As a result, I wound up getting my B.A. in Ethnomusicology in 2001, my B.F.A. in Jazz Studies in 2004, I did a year of graduate work as an Associate Instructor under David N. Baker (a true pioneer in jazz education) in 2006-2007, and then went on to Columbia University where I received by Master’s in Arts Administration, focusing on intellectual properly law and business.

In 2014 I was awarded a Hutchins Fellowship from the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard University to consolidate the research on my father’s music and life that I had been compiling since the age of 21 (I am 38 now), to complete a book, produce a documentary film, and to launch The Woody Shaw Institute of Global Arts. In essence this is a series of projects intended to preserve and present my father’s life story as embodied by the multifarious articles (both tangible and intangible) of his vast body of work, his artistic outlook, and his unique musical philosophy.

When and why did you establish the Woody Shaw Institute of Global Arts and what is your mission?

The Woody Shaw Institute of Global Arts is a vision that was birthed through the process of realizing the true depth and magnitude of the contributions of artists like Woody Shaw, who spent each and every day of their lives assimilating the subtle cultural nuances and influences of the world into their art. The full mission can be read at www.woodyshaw.com/institute, but in short, it is to preserve, present, and build upon the aesthetic as well as the symbolic and the social, within Woody Shaw’s worlds of creative thought.

The purpose is bi-drectional, in the sense that I am aware of the need to both preserve and nourish the history, so to speak, but also to keep reinventing, questioning, reexamining, and reimagining the propositions of my father’s art through the introduction and exploration of new interdisciplinary forms and relationships, sometimes cross-cultural, sometimes trans-idiomatic, which speaks to the “global” scope of this endeavor. What I am not interested in is trying to replicate or imitate, and do not think my father had much patience for that either. He was a constant researcher, student, and explorer when it came to music, to sound, symbolism, message, meaning and the organization of his ideas.

My mission is to present a model that serves as an alternative to our conventional institutional and educational formats; that treat the arts and humanities through the often blurred lens of social science, or that entrap the biographical narratives and obfuscate the brilliance of deceased artists to forgone conclusions of tragedy for the sake of sensationalism, or to some clumsily misaligned political or social ideology. I think many of the institutions that have appropriated the world “jazz” have rendered the word almost entirely devoid of meaning by completely overlooking the tremendous sacrifices undergone and pains suffered by the countless human beings who gave so much of themselves, and who were so committed to expressing their unique forms of intelligence and individuality, literally at all costs. I think it’s time to start shining a much brighter light on the humanity of the many long lost and forgotten originators who paved the way for what today gets called “jazz,” with so little if any soul or respect for the history behind that word, which it seems any and everyone can just appropriate, redefine, or oversimplify for their own personal or professional benefit.

There is a suggestion, at least in the complete name of the Woody Shaw Institute of Global Arts that your goals for its establishment go beyond the jazz music your father embraced and mastered. Talk about what appears to be your broader perspectives on the development of the Institute.

The institute will draw from Woody Shaw’s body of work not as a rhetorical or cultural cliche of jazz’s “greatness,” or as evidence of its own ingenuity alone, but as part of a starting point to inspire perhaps new or newly-inspired trajectories of thinking, hearing, listening, and creating art, including but not limited to music. I am interested in interdisciplinary and complementarity when it comes to the arts and artistic re-interpretation. Given the broad range of creative and cultural influences that Woody drew from, I have no doubt that he would have wanted his music to inspire and be applied within many other domains of creative self-expression than what the jazz CEOs and professors of the world call “jazz.”

When it comes to the essence of what this thing once was, if Woody Shaw is to be regarded as one of the “last major innovators,” which we know he was, then his music alone should have enough to teach us about what jazz actually is, not to mention where it comes from, and where it can still go. We don’t need to try to play “Woody’s greatest hits” or to run his arrangements into the ground at a much lower level of artistic ingenuity and quality than what he already originated in order to convince ourselves that we are doing justice to the “jazz” agenda. His music speaks for itself, as well as for the music’s entire history. He made certain of that, and both his predecessors and successors loudly attested to that fact.

I am of the belief that there is no sense in calling something by its name, especially if I already know what it is. However, I think many people would agree that the name Woody Shaw and the word “jazz” in its most indigenous sensibility, are fairly synonymous. But at the same time, Woody Shaw strove to transcend any cliches or limitations that were placed on his music or on his artistic identity. That was something he had to fight against throughout his entire life and career, and it is precisely because of his willingness to endure that artistic plight that many people have been able to legitimize themselves as “jazz musicians.” It is because of those sacrifices to be an individual artist at all costs that certain people have been able to validate themselves and their musical ideology without taking half as many risks or paying a fraction of the price to be truly great. So basically, while the essence of our music and where it comes from will always be present, the plight of evading contrivances and defining ourselves on our own creative terms continues.

More recently you’ve launched a campaign to fund a Woody Shaw documentary. Where are you with that project and how might folks continue to assist those efforts?

The campaign has gone very well. I’m not able to disclose numbers at this time, but the project received some very generous support and was backed by some generous and well-respected individuals in the community such as Steve Coleman, Jason Moran (both Associate Producers of the project), Brian Lynch and others.

I have been very inspired to receive constant offers from up and coming filmmakers and film crews who are eager to be part of this project. So I’m currently recruiting, conducting interviews, raising some additional funding, and expect to complete a rough cut by spring 2018.

I was honored that the project, titled Woody Shaw: Beyond All Limits…, was recently chosen as an official selection for the Works-in-Progress (WiP) program at Cucalorus FIlm Festival in Wilmington, NC (Nov. 8-12, 2017). I’m feeling pretty inspired by that, and look forward to a few more developments by the end of the year as well. Read more about the program at www.woodyshaw.com/cucalorus

To support the documentary project, visit www.woodyshaw.com/film.

Woody’s recorded legacy has lately been enhanced by several posthumous, previously unavailable releases. Are there other previously unreleased Woody Shaw recordings in your pipeline?

Well, The Tour (Vol. 2) with Woody Shaw and Louis Hayes is due out on August 25, 2017. I produced and wrote notes for this series. The CD is on HighNote Records, formerly Muse Records. As you probably know, we recently lost a very important figure in the jazz world, Joe Fields, who originally signed my father to Muse in 1974 and recorded Woody all the way until he signed with Columbia Records in 1977. That Muse period is a very historic era in jazz, marked by so many great recordings by Woody Shaw and his contemporaries. The sound of that era lives in those recordings and so much can be learned, felt, and remembered about where this country was at that time. I will do what I can to make sure that music continues to be heard and re- released.

As far as other previously unreleased material goes, well, I think you know the answer to that… Yeah, there are plans.

Beyond where you’ve ventured with the project thus far, what would you like to be remembered as the impact Woody Shaw made on the music?

Woody Shaw’s impact is only now being realized for its importance, really. The inherent musical complexity, the creativity and philosophical depth of what Woody put into his art and what he expressed is, quite frankly — epic. And he meant for it to be. It captures precisely what he was encountering as a human being; as a Black man, a creative artist, and as a deeply thoughtful and proud musician concerned with the state of affairs in the world and equally committed to improving his environment, and the human condition, through his art.

www.woodyshaw.com/woody-iii