Just in case you missed it, the Independent Ear is all about spotlighting enterprising musicians. One such artist is most assuredly drummer-bandleader Gerry Gibbs. From his Thrasher Dream Trio dreaming big with such masterful partners as NEA Jazz Masters pianist Kenny Barron and bassist Ron Carter, to his Thrasher Big Band, to his Electric Thrasher Orchestra Gerry Gibbs keeps himself busy. So we figured a few questions were in order, starting with seeking some insights into all that thrashing!

So what’s up with that Thrasher moniker you use for your productions and your various band configurations?

Gerry Gibbs : Lol, oh man this is really crazy. Back in 1986 The Don Pullen/ George Adams Quartet had come to LA. I had not moved to NY yet which happened about a year later. During that west coast tour of their band, I had made real good friends with Don. Almost every day we would meet to jam and at night Don would hang out with me and the girlfriend I was with at the time after the gigs to go eat, so we did a lot of hanging, playing and laughing that week. I had already been a huge fan. When their tour ended Don had told me that we would do something musically together once I moved to NY. One week after they left California, Don called to tell me the horrible news that their drummer Dannie Richmond had died and that they were going to keep a month tour they had coming up. He asked if I could go but I couldn’t because of conflicting commitment with my Father [the great vibraphonist-bandleader Terry Gibbs] and Buddy Defranco. Lewis Nash ended up being their second and last drummer and fit that band like a glove. When I got to NY , Don asked me if I could sub for Tony Williams and do 3 rehearsals with he and Gary Peacock for his debut Blue Note release “New Beginnings”. Don plays the piano very aggressively and much of the time with his knuckles and fists. During the first rehearsal Don had broken 2 black notes off the piano. I looked at Don and said, ” Oh man you are a “Thrasher”. The word “Thrasher” to me just sounded like a guy who just broke black keys off the piano. He laughed and thought it was funny to call him that.

Fast forward from 1988 to 1995. I signed my very first solo recording contract with Quincy Jones for Warner Bros to have him be the executive producer and former Crusaders drum legend Stix Hooper to produce it. I had a steady band at the time so we didn’t even need to rehearse for the record. I recorded a song I wrote for Don Pullen and called it “Pullen/The Thrasher”. Quincy said he really liked the tune but asked me if we could change the name of the song to just the “The Thrasher” and put a dedication next to the title for Don. I, of course said yes. Then they came back to me and asked if I was cool with them calling the album “The Thrasher”. Well once the CD came out we were set up to tour all over the world and of course they started calling my band at festivals “The Thrasher Band”.That CD got a lot of press and a few awards for that year and all the critics referred to me as Gerry Gibbs The Thrasher. It wasn’t something that I wanted but then back in NYC everyone started calling me that so it stayed and every project after became The Thrasher Something? Band. Even to this day guys like Randy Brecker don’t even call me Gerry. We played a week a few years ago with Patrice Rushen on piano and he kept introducing me on the mike as The Thrasher on Drums! So there it is. I gave the name to Don Pullen and then it ends up back on me as my nickname lol.

Given our 21st century independent artist recording scene, where the figurative record company pursuit is not the same as it once was, what’s been your ongoing production relationship with Whaling City Sound?

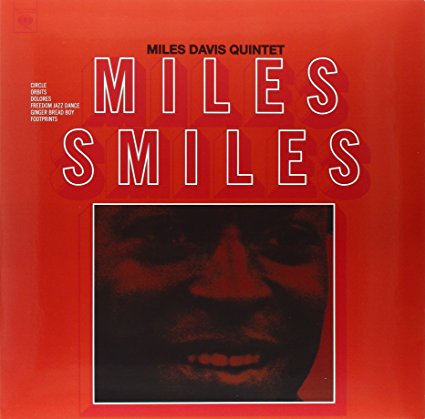

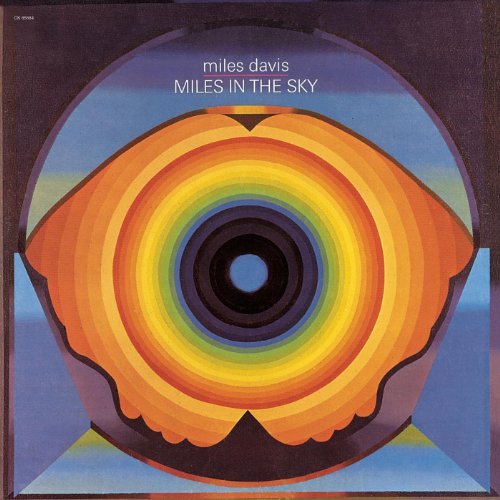

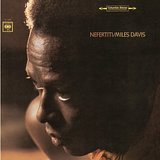

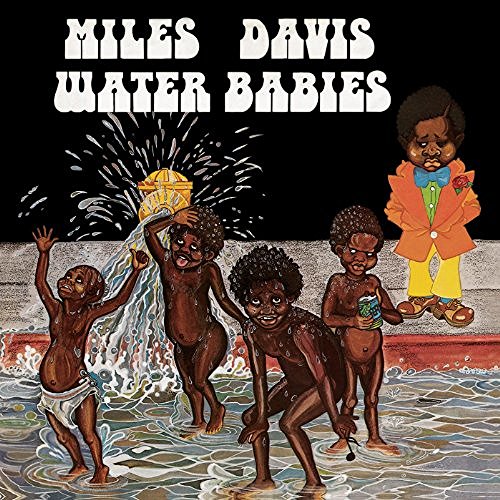

Well thats been a complete blessing for me. I have about 50 record concepts in my head that I want to do before I die. I had recorded 4 albums as a leader when I first met Neal Weiss the president of that label. From 1998 to about 2005 I had a girlfriend that lived in San Antonio and I was spending all my free time there. People have no idea that there is a huge scene with about 100 great musicians between there and Austin. I started doing music projects since I write so much music. One particular project was something I did at a jazz festival down there going on before Dr. John. I wrote music for a full big band, 16 gospel singers, 2 keyboard players, bass, drums, percussion, sitar, a rapper and a guy who did spoken word through a bull horn, and he recited everything with a real militant tone yelling through the bull horn accompanied by gospel singers singing really beautiful long voicings and the big band sounding like a 1970s Baretta TV show theme with the rapper also rapping with an electric tuba playing all the bass lines. People were really flipped out over this and Neal’s brother was in the audience and recorded some of it with his video camera to share with his brother. I got a call a week later with Neal asking me if I had recorded that because he was interested in putting it out on his label. I told him no but that I loved doing this live but it wasnt what I wanted to document on CD at the time. I told him I was just working on a live Big Band recording of the band I had that played a weekly gig in front of 100s of San Antonio music fans each week and if I put anything out I would want to have it be this because I had also written all the music or arrangements and really wanted it documented. He listened to it and bought the masters. Later I wanted to record a project I had been doing with a band in LA of all the Miles Davis Music from 1967 to 1975. That time we recorded a double CD with guys from LA, NY and San Antonio Texas. I later did gigs with that music inviting Nicholas Payton, Dave Liebman and others . I also got 8 of the original members of the Mile Davis Bitches Brew record to write the liner notes and Neal Weiss got Jo Gelbard who was Miles art teacher to do the artwork painting for the cd cover.

Neal always let me do what I wanted in the studio because I didn’t go into recording a CD just because it was time to do one, but because I had the whole CD planned out in my head. So he always gave me 100% freedom to produce my vision. Then he would take it and package it with his team so beautifully and in ways most independent record labels don’t. He makes big booklets and takes a lot of pride in making the package important to go with the music he puts out.

After that 2nd recording for The Whaling City Sound Label I wanted the CDs I was recording to do better radio wise and selling wise. I had been basically recording from a more vane approach, recording things that I wanted which was not selling CDs or getting radio play, and I actually knew this would be the outcome while I was recording them! So for the next bunch of recordings I decided to record differently. I had a meeting with Neal Weiss and told him I wanted to change gears and make some CDs for radio airplay without having to go commercial. I wanted to record the next few CDs where I wanted to have each song connect in a way harmonically, rhythmically, tempo wise, and subliminally where maybe I could create the same effect that certain albums that I started listening to 40 years ago had on me . There are certain recordings that when I would listen to them they would take me on a journey where I would listen to them over and over and over and still listen to them over and over 40 years later. I was given the green light to contact Ron Carter and Kenny Barron to start The Thrasher Dream Trio for this plus over a 3 recordings period have such guest as Cassandra Wilson, Roy Hargrove, Larry Goldings, Warren Wolf and Steve Wilson. In a 23-month period, Whaling City let me release 3 CDs with 3 totally different concepts. We were lucky and fortunate enough to go to #1 three times in a row on the Jazzweek International Jazz Radio Charts – for 15 weeks total – and stay in the top 10 for 38 weeks out of a 21 month period, as well as stay in the top 50 for 14 out of 21 months with the 3 CDs! That was really exciting for all of us. For the next 2 that will come out in 2017 I recorded a double CD. The 2 CDs for the first release in Feb 2017 have a thread from the beginning of CD 1 to the end of CD 2, but the 2 CDs also have 2 different purposes. I also produced a 2nd CD for Whaling City of a project dedicated to McCoy Tyner with Benito Gonzales and Essiet Essiet that I started a long time ago, but I decided to turn it into a co-op project because the 3 of us were equally involved in the evolution of how we were documenting the music, and I wasn’t really dictating where the music was going.

Your Thrasher projects have ranged from trio to larger ensemble to full-blown big band. What’s next?

A few new things. As I said before, I have 50 recordings in my head I want to complete before I die. I have 10 solo recordings out on various labels. I also have a few projects with my Thrasher All Star Big Band with many different guest who have performed with it over the years, such as James Moody, Clark Terry, Jon Hendricks, Tom Harrell, Nicholas Payton, Paquito D’Rivera and many others. I also have my Electric Thrasher Orchestra which does all the music of Miles Davis from 1967- 1975. I also have plans on doing a new trio recording, hopefully soon, with Stanley Clarke and Geri Allen which we have been talking about since last year, but have to get our schedules to all work at the same the time. Outside of what I did with the Thrasher Dream Trio with Ron Carter & Kenny Barron, I really wanted to start a new band where I could rehearse 2 or 3 times a week and have a band available to tour anytime. As you can imagine thats completely impossible with Ron and Kenny although we are I believe going to a gig again sometime in early 2017. I think management is trying to figure out a time and date. Wish I had some info on that now but nothing is confirmed yet.

So as I was saying, I really wanted to start a new project but of course trying to find the right guys for the very specific thing I wanted to do was really going to be the biggest challenge. I needed to find really great guys that I could sit down and explain what I was looking for conceptually and then see if I could get a commitment to rehearsing 2 or 3 times a week for 3 or 4 months to create the concept I was looking for and then head into the studio to record a double CD with 28 of my arrangements, and record them without having to read any music. After searching for about 6 months one night I met pianist Alex Collins. Alex is not well known but has worked with many of the best musicians around. The first get together was for us just to play duets for an hour and then go on a long car ride so I could play it back for him and tell him what I was looking for. I told him I wanted to record 12 arrangements I did of Weather Report Music and then played him old versions or electronic versions of 16 originals. The concept for the originals was that I wanted it to sound like 16 different bands on the cd.

When I was a kid I would make cassette tapes of different artist and imagine making a cd one day where it sounded like a compilation recording but it would be with the same band. I wanted him to practice playing acoustic Piano, Fender Rhodes and organ at the same time, playing on one with one hand and another instrument with the other. When I heard him sing, I also had him add his voice to a bunch of things, having him sing wordless lines either in unison or harmony while playing a solo. I also wanted to find an acoustic bassist who could also play electric bass, preferably with a pick, and play his electric bass through a guitar amp so that he could solo and sound like a guitar player. I have played with Hans Glawishnig for 25 years and knew he was the one and would commit to everything. I play drums, percussion, vocals, and all synthezisers as well as pre-recorded electronic sound scapes, harp, wood flutes and other things…

Thirty years ago I use to go into the studio and record all kinds of electronic sound scapes and pre-recorded voices, poems, etc, and then the band would have to record playing to the pre-recorded tracks.. Back then people thought it was too crazy. We didnt have computers that could do that back then so I would have 2 or 3 cassette tapes ready to activate during live shows and we played along to it. Now this concept has came back, but done a lot simpler due to having computers. People are not weirded it out by it so I am returning to using this technique on a few things during my original music part of this new double CD. The new band and double cd will come out in February on Whaling City Sound Records. The band is called Thrasher People and the new CD will be called “Weather or Not”.

PETER ERSKINE: “Joe Zawinul always had the utmost respect for maestros Kenny Barron and Ron Carter. I am certain that their Thrasher Trio-mate Gerry Gibbs’ name would have been added to that select list had Joe been able to hear Gerry’s realization of the music of Weather Report as played by his new trio that includes Alex Collins on piano, Fender Rhodes, organ & vocals, plus Hans Glavishnig on acoustic bass (whose playing on this CD bears an uncanny resemblance to maestro Carter’s). Here is a unique reading of Weather Report’s music that is totally fun to listen to. As an insider, I can say that this album sheds new light on the WR canon while spotlighting the intrinsic talent and sounds of Gerry’s new band. I feel the better for having heard this recording.

P.S. Jaco would have loved Hans’ playing on “A Remark You Made” … I know that I do.”

You must certainly have a fertile rolodex, given the calibre of players you’ve engaged for these projects. What’s your philosophy about the musicians you engage to produce these various projects?

Interesting question. Before I contact anyone for a project I know 99% what it will sound like before going in to record. Many musicians like to go in and see whats going to happen but for me I can already hear the cd completely in my head and use the people that will understand 100%, and will be able to pull it off without me ever telling them what to play, because they can completely understand the concept and direction for each CD. I have 10 solo CD’s out and a new double CD as well as a CD that I produced and am co-leader on. In every record I have ever done, as soon as I get the green light from the record company, budget, etc, I will sit down and map out on paper who is on it, pick all the selections and map out how I will write my arrangements, and do that all in about an hour and never deviate from that. I will then take a few days to arrange the music that I chose in that hour and thats it. The CD will sound 99.9% exactly how I envisioned it in that hour. dI have about 40 or so more ideas for projects to record and hope while I am still on earth I will get to record them all.

With Ron and Kenny, there isn’t anything they have not heard or done so its really easy because their resources encompass everything thats ever been done. I could have recorded a fusion cd, a completely free CD with no music, or even a country western CD with those guys.

I will go a little more into detail about the last 3 recordings being that your previous question and this one have a thread to them for me. For the first CD we did I had a compositional and harmonic concept that I wanted to thread together for a story from beginning to end. Where there was not any type of song concept in mind, there was a flow of the type of chord forms, rhythms, tempos, and concepts I wanted to do threading songs together from song 1 to the last song. Without having to go commercial with any of the recording this time I also wanted every song to be played on radio and really kept that in the front of my concept for this project. I wanted it to do well on radio, which the record label and I discussed at length. I thought of a way to try the best I could to keep a flow and try to keep the listener engaged by taking them on a certain ride based on thinking of each song like a musical sound track from beginning to end. I also explained this to Ron and Kenny. Ron really was so conscientious in the studio about the music flowing a certain way from song to song. He made a ton of incredible musical decisions not just thinking of each tune separately but making everything fit. We even recorded the CD in the order it was going to come out in which I try do when possible. That first CD in a few weeks went to #1 on the international radio charts for 6 weeks and got a best solo Grammy nomination.

For our next CD I wanted to record a whole CD of my R&B favorites from the 70s and a few from the 60s. I wanted to record all the most beautiful melodic ones that would have the listener, if they only heard one song from the CD, not be able to get that melody out of their head. These songs were already huge hits that millions loved so there would be no denying that people would love these songs, even if they didn’t like the way we played them. But with Ron and Kenny playing them how could you not. I also did not want to try and be too over the top in trying to be hip and show other musicians how much I could re-harmonize these tunes and even like a lot of people do make the song sound completely different. What I wanted to do was to make each song swing but also have the same recognizable melody and chord progressions. I, of course had to make up song chord changes for soloing since most of these songs didnt have a solo form built into them. I only used chords that were already in the songs and just made them make sense for soloing. I know radio, and jazz fans are huge fans of these songs. I also know radio DJs can not play the original versions on their shows because it didn’t fit their format so I set out to make these great R&B classics sound like standard jazz classic. I added Warren Wolf on vibes, Larry Goldings on Organ and Steve Wilson on saxes to bring some more colors to this CD. Within 3 weeks of release this CD went to #1 on the international radio charts for 7 weeks.

For the latest recording I had an idea that takes really special people to make happen. Ron Carter and Kenny Barron are no doubt to millions of fans and musicians some of the best “just sit down and play some jazz with no arrangements” kind of musicians,” so that was going to be just 1 of the elements for this latest cd. I had recorded some of my gig and rehearsals with Ron and Kenny in the past and we would sometimes just jam a little bit and I knew I wanted to do a cd with them that really had that loose element. I went to the label and to the guys and told them what I wanted to do and everyone thought I was a little crazy but indulged me. The first idea was that I have always been a huge fan of what they now call “Lounge Music” or music that I call “Elevator or Doctors Office Music “from when I was a little boy in the early 70s and would pick only songs that were so well known from then, yet people knew the melodies but not the names. The second idea was to add guests that never worked or recorded together before so that there would be surprises for us musically. So I first called Cassandra Wilson. She is not like most singers who desire to know ahead of time what songs will be chosen; she can just walk in and sing with no arrangements or preparation. If needed she can look the lyrics up on line just before. This is Cassandra’s strength to be able to do that and so she was choice #1.

Roy Hargrove and I have played at a million jam sessions for the last 30 years and not only does he take his own and other peoples projects serious but he even takes a jam session serious. He always takes the perfect length solo and treats whatever is going on even at a jam session seriously, so he was my first instrumental choice. To make this even more exciting I wanted it to be done with no rehearsals or discussion before we recorded. Just show up and I will tell you what we will do. The third element was to record this only in front of a live audience made up of only musicians and music industry people people. So The trio recorded 3 shows and Cassandra and Roy came in and recorded one show in front of a packed audience at Systems 2 Recording Studio. I would pass out the song, the audience would not be allowed to say a word and I would take 3 or 4 mins to discuss the form and solo order and then we would do just one take. All the songs were known, but not songs that guys usually get together and jam on, so everyone had to look at these lead sheets. In the end how could you not get brilliant performances with Ron Carter, Kenny Barron, Cassandra Wilson and Roy Hargrove! Everyone really took this idea so seriously and personally and it was a fun 2 days that I will always remember.

My latest new project, as I mentioned above, is called Thrasher People, which is made of 2 very young guys. Alex Collins on piano, Rhodes, and organ, as well as using his voice as an instrument, acoustic and electric bassist Hans Glavishnig. I also have a new release I released myself of a Solo Electronic Music project I call Reni Beats. Each song is electronic but I am not using any loops or samples. Whn you hear 20 or 30 voices thats my wife Kyeshie and I doing 30 overdubs.I also created videos that I shot using animation to go with the 20 songs we recorded. Its something I have been into for a long time. I had a lot of fun touring a few years ago with Flying Lotus, so it had been on my mind to do a project of my own. It can be heard on YouTube, but I actually am in the process of re-naming it back to my name and adding a few new things to the cd

I will also be trying out a new project in March 2017 for 3 nights at Dizzys Club Coca Cola. The people I handpicked for this are Tom Harrell, Steve Wilson, Robin Eubanks, Buster Williams and Alex Collins playing all of his instruments and voice. Not sure what will happen beyond these gigs but we will see.

Was your father’s career perhaps some incentive for your Thrasher Big Band project?

No, not at all. But everything I know about understanding a big band comes from him and his big band. Today you hear big bands made up of cliques of friends, and most of those bands dont play together, and play really sloppy and out of tune. Some musicians will make an excuse that this is more about vibe, but that isn’t what I want my band to sound like. Now dont get me wrong, there are a few big bands that I really loved for their vibe, like Sun Ra or the Globe Unity Orchestra. My all time favorite big bands that I borrowed from their sounds are many. Here is what comes to mind and not in any order. My Pops, Basie, Ellington, Buddy Rich, Fletcher Henderson, Woody Herman, Les Baxter, Esquivel, Jaco Pastorius, McCoy Tyner, Louie Bellson, The Tonight Show band from the Carson days, and there are many others.

I always love The Lincoln Center Jazz Band because Wynton knows how to make his big band sound like a band, not 16 guys just reading, phrasing and playing all individually. You can’t do that in a big band. When I was spending a lot of time in Texas (where I had a girl friend for many years) there were many great musicians that lived around San Antonio and Austin that had gone through the North Texas State program and each guy really knew about many different big bands and different concepts for big band. Anyone can play 2nd trumpet or 4th trumpet… anyone can!! And I mean read the parts! But not everyone, when playing in those chairs, really understands what they are supposed to do in those chairs. How to blend, how to follow the lead trumpet player, phrase etc. I hear big bands playing where everyone phrases how ever they feel. Thats not a big band, Thats just 16 guys all playing at the same time. There is a real art to that. When I picked the guys who made my big band recording I picked only the best they had in San Antonio and Austin. Some guys would say to me why dont you get this guy or that guy, and I would ask is he the best for that chair? Some guys would say no, but he is a great guy and I would pass. I only wanted people who were the best available for each chair. We played every week for 3 years while I was spending most of free time there. I wrote 12 originals and then augmented a bunch of my pops music. That band had some great guests… my Pops, James Moody, Clark Terry, Jon Hendricks.

In NY when I put my big band together to play live I chose guys that really know big bands and big band history. If you really want a vibe there is nothing better than veteran guys who, when playing in whatever chair really understand what they have to do to make every voicing blend, make the music groove no matter if it is swinging, funky, completely free, whatever. How to blend and phrase as I said before, etc. When you have people like Tom Harrell, Nicholas Payton, Marvin Stamm, Bijon Watson, Lew Soloff, Joe Magnarelli Paquito D’Rivera, Eric Alexander, Gary Smulyan, Robin Eubanks, Steve Davis, Vincent Herring, Mark Gross , Jerry Weldon and others all on the same stage… well these are guys that no matter what the music is have the utmost understanding of how to make a horn section work. These are not cliques of guys that I chose, but guys who know the history of every big band thats ever played and how to play as a band no matter what the music is.

I understand you grew up with Ravi Coltrane. Any chance of the two of you engaging in some new project or other?

Ravi played in my first Thrasher Band for many years. Those were great times and great bands…We did one CD, executive produced by Quincy Jones for his Qwest/Warner Bro. label. In that band Ravi was the only steady person for about 3 years. We did that one cd and toured alot for 3 years . In that band we had pianists Billy Childs, Brad Mehldau, Patrice Rushen, George Cables, Uri Caine, Aaron Goldberg, and Greg Kirsten. Violinists Mark Feldman and Rob Thomas; vibraphonists Joe Locke, and Stefon Harris,; and bassists, Darek Oles and Essiet Essiet. That band broke up around 1998. Since then I have done a few things with this band, and Ravi has done a few things in different bands of mine. We did do one reunion gig many years ago. I don’t really like to go back to what I have done because I have 40 other projects I want to document and tour with. Those were great times for all of us. Billy Childs, Brad Mehldau and Mark Feldman will from time to time bring up all the fun and laughs we had and I know for Ravi, because of his commitment to that band back then, that it was a great moment in time for him, but that was where we were all at 20 plus years ago, and now we are all in different places musically. I would like to remember what we did when it was in the moment and not try and re create it again. Sometimes I like to re- create old projects but for whatever reason, not that one. It was so much fun then and ide like to just remember it as that…..