Look up the word mellifluous and when it comes to bass playing, the name Rufus Reid certainly applies. The man plays the instrument with a dexterous sense of time and lower end gravity that is complimentary to whatever setting he is called to enhance. A native of Atlanta who grew up in Sacramento, Rufus Reid’s professional career commenced largely in Chicago. For some their earliest sightings of Rufus may have been as a member of Dexter Gordon’s robust 1980s quartet. His affiliations also range from Nancy Wilson, Stan Getz and the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra to Jack DeJohnette, Andrew Hill and Henry Threadgill. That sampling alone gives you a sense of the versatility of this sturdily built bassman with the distinguished head of gray hair, ready smile, and eminently approachable demeanor.

Rufus Reid’s current recorded endeavor is the just-released Quiet Pride (Motema), subtitled The Elizabeth Catlett Project, in honor of the late, great visual artist whose artistry obviously had a profound effect on Rufus Reid somewhere along his journey. To find out where this distinguished bassist-composer’s artistic sensibilities intersected with Ms. Catlett’s renowned work, we had a few Independent Ear questions for Rufus Reid. But first, you may recall our dialogue with drummer-bandleader Francisco Mora-Catlett (Archives: November ’13) on his latest recorded enterprise, AfroHorn Rare Metal. As a prelude to our dialogue with Rufus Reid on his new project I wanted to circle back to Francisco to get his sense of this superb tribute to his late mother, Elizabeth Catlett.

ON RUFUS REID QUIET PRIDE …

In our African traditions and in the work with strong African Identity the relationship between diverse Art Forms is always fundamental and more than feeding on each other it complements and magnifies the context in which originally is created. Rufus Reid’s “QUIET PRIDE” a set of compositions inspired in the work of Elizabeth Catlett, in my own interpretation; successfully emphasizes the creative relation between art forms that surge from the traditions of an African identity and its continuity. Dance moves to music, inspired in the spoken word, song tells the literary story, and visual art illustrates it. I became aware of this work some years back, when trumpeter Cecil Bridgewater told me that Rufus Reid had written pieces inspired on my mother’s sculpture work. I remember distinctly my mother asking me, is he playing somewhere? lets go hear him. We did, Rufus Reid was working in a Jazz club in the Village and he was so impressed that Elizabeth Catlett had gone to hear him play; she invited him and his wife Doris to come to Mexico to visit in her Home-Studio in Cuernavaca as to become familiar with the process and way she worked. There are similitudes in the the way you solve an esthetical problem in form and shape as you carve wood or orchestrate music, and sometimes is the wood or the music that establishes the direction in which the work tends or has to go.

My mother always accompanied her work with her music, specially during the last part of her life. You could walk into her studio and hear from Mahalia Jackson, Otis Redding, Louis Armstrong, to Aretha Franklin or Miles Davis while she was working. Rufus Reid’s Quiet Pride brings closer the relationship and the inspiration that we draw from all art.

Quiet Pride is such an inspirational work; the compositions are fabulous, the arrangements are rich, lavish orchestrations with surprising vocal melody effects, and a great choice of master musicians that delivers beauty in these renditions; it is an epic marvelous work inspired by great American Art.

Thank you Rufus, I know my mother loves the work…

— Francisco Mora Catlett, January 30th 2014

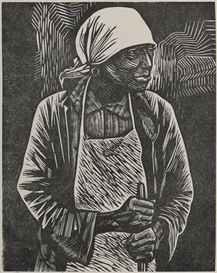

The artistry of Elizabeth Catlett

Independent Ear: Quiet Pride” strikes me as a work that at least in part is a realization of a dream of yours. Is that an accurate characterization?

Rufus Reid: Actually, you are quite correct, this project has been a dream of mine that is finally happening! A huge part of the dream was to have the music rendered by some of the best and seasoned players around taking the music beyond my wildest dreams. This is my very first professional commercial recording of my large ensemble writing. This is very exciting for me to experience at this stage of my career.

How has Elizabeth Catlett inspired you to write this large-scale work?

Over twenty-five years ago, I acquired a book about her life and her various types art works. To be honest, at that time I knew nothing about her, whatsoever. I did enjoy and frequently did go to art museums, but I didn’t really know much about it at all. I do remember, at the outset, this book about Elizabeth Catlett was impressive. However, that was it. In 2006, I became aware of the Dr. Raymond and Beverly Sackler Commission Competition Prize administered through the University of Connecticut at Storrs from my participating in the BMI Composers Workshop! The main emphasis of BMI Composers Workshop environment was to assist the composers to step outside their “box,” meaning his or her comfort zone. That year was the very first time this commission was offered to the Jazz community. In order to apply, you had to propose what you wanted to write. I had nothing to lose, so I proposed to write music inspired by Elizabeth Catlett’s sculptures. After all, I had this incredible book in my possession. After checking out this book with much more interest, I became more aware of her creativity and totally in awe of her beautiful art. I knew I wanted to create something that would make people more aware of her and her art. At the same time, I wanted people who knew about her to become more aware of the art of Jazz, me, and my music. The challenge for me was to make the music rise to the high level of her art. This was only the beginning of this incredible journey I am on.

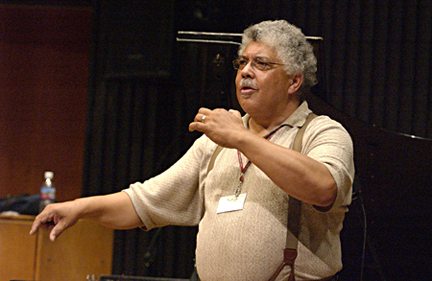

Rufus Reid at the Quiet Pride recording session

So often, unfortunately large-scale works like this become purely recording projects because the cost to stage them is too prohibitive. Do you have anything in the works to stage this work?

Yes, the size of this ensemble does require a lot of money, interest and work to perform the music live, but it can be done. I am happy to announce the CD release performance will be March 12, 2014, at the Jazz Standard Club in New York City. A great deal of energy is being put forward in developing and contacting appropriate venues to have more performances. In addition, another important aspect is that colleges and universities across the country are being contacted to have their music, art, women’s studies departments, and the community at large to collaborate by interacting with one another. In these cases, I would conduct the music and give lectures, etc. So far we have had very successful events at the University of Connecticut/Storrs, the Manship Theater in the Shaw Center For The Arts which is affiliated with the Louisiana State University, and at Bucknell University. The first two venues exhibited selected art works of Elizabeth Catlett coinciding with my concert performances.

I’ve gotten the sense that in the last decade or so you’ve really begun to dig deep and concentrate quite a bit on composing. Is that an accurate assessment?

Yes, you are very correct, indeed. I have always been intrigued about composition. I have had the great fortune to be associated closely with some incredible composers throughout my career. Fourteen years ago, I began to make a concerted effort to learn more about composition and what is necessary to become a real composer. I have never studied composition academically speaking. I just ask question and buy books on the subject. I am totally smitten with the mere process of composition.

When composition becomes such a central quest, is there any sense that your actual playing may take a back seat?

Eventually, one day, I suppose, my playing may take a back seat to composition, but that will not happen for a while. That being said, I do feel a direct impact on my playing has occurred. I now think very differently about “how” I begin, develop, and end my improvised solos like never before. So, in some ways, my soloing has become more thoughtful and that has been a very good thing, in my opinion. My note choices and rhythmic placement have become more important to me than how many notes I can play, more than ever.

How did you go about selecting the musicians to make this work come to life?

Choosing the musicians for this project was easy and not so easy. I really didn’t want a fixed band to work with. I wanted a fresh set of seasoned players who understood the big band setting, but were open to a fresher approach. I wanted players I knew personally, who were focused, strong, and possessed an individual voice already established. I also wanted a mix of genders, ages, and experiences to pool together to become “one.” I was blessed with a group who brought their “A” game to this project. I could not be happier.

Any further reflections on this project?

Meeting and becoming friends with Elizabeth Catlett has truly enriched my life on many levels. Studying more about the art world has also been truly educational. I had no idea that this project, art inspired by art, would be so fulfilling. I have certainly been empowered to continue my path as a creative composer.

The master at work

www.rufusreid.com www.motema.com