Blessed with a spiritual quality reminiscent of the vibrant 60s/70s African American cultural consciousness scenes, and indelibly linked to Afro-Caribbean folkloric elements, percussionist Francisco Mora-Catlett has made two exceptional recordings over the last two years; these have included 2012’s striking Afro Horn MX and Francisco’s 2013 successor AfroHorn Rare Metal releases. Based on this year’s powerful followup, clearly Francisco is plumbing a deep well of distinctive thematic music.

I first met Francisco Mora-Catlett in Detroit back in my Great Lakes Arts Alliance and later Arts Midwest days of providing service to the jazz community of the Great Midwest. Back in those days Detroit and Chicago ran neck-and-neck in terms of activist communities of self-determining musicians, and Francisco was right there in the Motor City, working with such stalwarts as our mutual friend the late pianist-composer Kenn Cox. Some may recall Kenn Cox from the old Kenny Cox Contemporary Jazz Quintet that made two rare recordings for the Blue Note label. It had been more than a minute since I’d seen or heard Francisco Mora-Catlett, so the arrival of last year’s Afro Horn MX was a welcome sound. Immediately the mind drifted back to some of my undergrad African American studies courses at Kent State and my personal discovery of Henry Dumas’ powerful short story “Will The Circle Be Unbroken?” which is the thematic underpinning from which Francisco launched that first MX recording.

Now with his 2013 followup AfroHorn Rare Metal, clearly some measure of catching up with and inquisition of Francisco was in order. But first, I wanted Independent Ear readers to get to know a bit about Francisco Mora-Catlett’s background, particularly since he derives his hyphenated surname from renowned artist-parents.

Born in Washington, D.C. and raised in Mexico City (where I started studying music), my parents are African-American sculptress Elizabeth Catlett and Mexican painter Francisco Mora. I was a session musician at Capitol Records’ Mexican division. In 1970, I earned a grant from the Mexican government to attend Berklee College of Music in Boston, where I studied composition, and drum set with Alan Dawson at the Center for Afro American Artists Elma Lewis School, and African percussion with legendary Nigerian drummer Babatunde Olatunji.

From 1973 to 1980, I was a member of the internationally renowned Sun Ra Arkestra. Later I settled in Detroit working, touring and recording with outstanding musicians such as Kenny Cox, Roy Brooks, Harold McKinney, Donald Walden, Ali Jackson, Wendell Harrison, Sherman Mitchell and Marcus Belgrave. In 1986, I made my first album as bandleader: “Mora!” a progressive Afro-Jazz project. Thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, I was able to study with Max Roach in New York City, performing as a member of Roach’s advanced all-percussion ensemble, “M’Boom”. I played on two of Mr. Roach’s Blue Moon albums: “To the Max” (1990) and “Live at S.O.B.’s New York” (1992).

In 1993, I was appointed a Visiting Minority Associate Professor in the School of Music at Michigan State University, where for 10 years I taught students: “percussion that derives from the concepts and traditions of the African presence in the Americas.” In Detroit I played drums and percussion on “Bug in the Bassbin,” the 1996 debut single by Detroit techno producer Carl Craig‘s groundbreaking jazz/electronica fusion project “Innerzone Orchestra”. I also appeared on the 1999 release of Innerzone Orchestra’s “Programmed.” Later that year, I launched my second album, “World Trade Music”, with fellow Innerzone artists Craig Taborn and Rodney Whitaker. In 1999, my contributions to the music world were recognized in Britain’s “Straight No Chaser” magazine*(1): “Like the most elegant hand-tooled walnut dashboard on the flight-deck of a Space Shuttle, is the sound of Francisco Mora Catlett.” My parting contribution to Detroit’s music scene was the creation of The Outerzone Band, featuring Marshall Allen and Craig Taborn.

Since relocating in New York City in 2002, I co-founded the Oyu Oro Afro-Cuban Dance Ensemble with my wife, Afro-Cuban dancer and choreographer Danys “La Mora” Perez Prades. With new recordings in New York City, my work as a percussionist and composer has been featured on two CDs for the Freedom Jazz Trio: New Under The Sun, featuring Francesco Tristano, and Live At The Bronx Museum; and Outer Zone 2010 Andromeda M-31, both with Craig Taborn.

In 2012, I released Afro Horn MX with an outstanding lineup of musicians: John “JD” Allen, Vincent Bowens, Alex Harding, Aruán Ortiz, Rashaan Carter and Roman Díaz. Writing in New York’s Downtown Music Gallery, Bruce Lee Gallanter described Afro Horn MX as being “Like the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Francisco Mora Catlett’s septet blends the ancient and modern as well as the African and Latin streams into a most delectable blend. … One of this year’s best.”

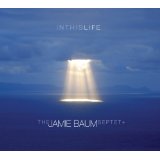

I’ve fortunately received significant acclaim for our new 2013 AfroHORN CD release Rare Metal, featuring Sam Newsome, soprano saxophone; Salim Washington, tenor saxophone, flute, oboe; Alex Harding, baritone saxophone, bass clarinet; Aruán Ortiz, piano; Rashaan Carter, acoustic, electric bass; Roman Díaz, percussion, vocals; Andrew Daniels, percussion; Danys “La Mora” Perez, Meredith Wright, Liethis Hechavarria, Sandra D. Harper, vocals.

How did your distinguished artist parents inspire your music?

They were always part and a crucial aspect in my development as a musician and a serious artist. Early in my commercial work in Mexico City I was consistently reminded by my father about not performing the classics and by my mother of not playing the blues. Encouraged to study composition with their uncompromising support, I was able to create a solid foundation in my early musical formation.

How did this AfroHORN project originate?

I joined Sun Ra and his Arkestra in Mexico City and, under his mentorship, came to the US. It was in Sun Ra’s house in Philadelphia where I was introduced to the writings of Henry Dumas, and where I read his short story “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” I was so impressed by this work that I wanted to be part of an Afro Horn Jazz Band, so I put together the first Afro Horn band in Detroit in the early 1980’s. The idea of a mythical, cosmic, musical instrument, originated in powerful traditions, that link the universal criteria of the African Presence in the Americas, and that defies shallow interpretation and definition of its manifestation, while clearing egoism and self rewarding pursuit, fascinated me.

For those who may not be familiar with Dumas’ story, what exactly is the legend of the Afro Horn?

My interpretation of the Afro Horn in the musical context, as stated by Henry Dumas in his short story “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” is highly descriptive and profoundly linked to the ceremonial and ritual musical traditions of the African Spiritual practices as they have evolved in the Americas; while first healing and raising the living condition of the communities that come from these traditions and later, because of its ties to a universal community… Henry Dumas wrote, “There are only three Afro-Horns in the world. They were forged from a rare metal found only in Africa and South America.” Is this a myth or true phenomena? That is the elusive and indefinable nature that characterizes the music derived from the African Heritage in the Americas.

Talk about the Afro-Caribbean folkloric quality to AfroHORN; how did you come to that as a central element of your music?

African-American folklore, Afro-Caribbean folklore and African-American music traditions are all elements, resources and an integral part of my work. I lived in Detroit in an African-American Community and I lived this experience. I have spent a lot of time in Cuba and I have researched the migrations and exodus of African derived people throughout the Caribbean, and how they arrived in New Orleans. The importance of Congo Square, as early as the 1800’s, to an already African American population, and among others the initial writings of Louis Moreau Gottschalk in such works as “Bamboula”, based on the music he heard in Louisiana. Those are valued manifestations of African elements in an already American Music. In my work, the African identity of the music that is called Jazz (that I prefer to think of as an American Classical Music) is extremely important, regarding its own nature, its elusiveness, and defying definition, while contributing and enriching to the universal freedom of the human spirit…

How did you assemble the musicians who play this music?

The musicians that work on my projects arrive from a similar state of mind and unconventional musical principles. What I offer the musicians is a blue print of the intended direction; with strong respect for each other’s creativity we all decide collectively where the music goes. I started working with Alex Harding in Detroit back in the late 80’s; we have always being strong supporters of each other’s work, and we have develop a language of communication. Sam Newsome, I met in New York City and instantly we decided we had to work together sometime soon. Salim Washington was always very supportive of the Afro Horn project, offering his home for rehearsals and participating in the early concerts in New York City. Roman Diaz has known my wife at the Afro Cuban Folklore Movement in Cuba, since she was 11 years old, and we work together on her Afro Cuban Folklore dance company OYU ORO in New York. Rashaan Carter loves the music, comes from Washington DC and he was introduced to me by Aruán Ortiz who comes from Santiago de Cuba where my wife is from. These musicians have a family and a community feeling for what we’re doing with the Afro Horn project. They are all unique in their sound and in their contribution. They are real sound with a wonderful sonic concept. I believe that working together with these musicians is one of my greatest and most unique experiences.

The AfroHorn crew; left to right: Aruan Ortiz, Sam Newsome, Francisco, Rashaan Carter, Alex Harding, Roman Diaz

What’s next for this AfroHORN project and do you see it continuing for the foreseeable future?

I truly believe in the idea of a music project that grows and has a relationship, in concept and direction, with another art form, literary in this case. They jointly represent an identity that in principle is always evolving, in continuity, around the need to express and manifest the freedom of the human spirit and that has longevity and a powerful future. Having the great fortune to work with giants like Sun Ra and Max Roach has taught me that cultural continuity, vision and perseverance, are essential to maintain the expressivity of an Artistic form.