Recently I polled some jazz business professionals asking the following question: If a young person (or otherwise) were to ask you how best to get started with their budding interest in jazz music, who/what would you recommend they listen to and what would you recommend they read to get a real ground floor sense of jazz and it’s evolution?

“I always tell them a great first step is to find the jazz station in their area… usually at the left end of the dial. I also tell them to look for jazz via other sources, such as satellite radio (i.e. Sirius/XM’s Real Jazz), though that’s more for listening (often there’s not the context you might get on an indie station). The next thing I tell them is to look for a few artists and/or styles of jazz that they like, that speaks to them.

In the “old days” I would tell them to go out and get those albums – or in more recent times, CDs – and to READ THE LINER NOTES!!! I still say that today, but not sure how many folks are still purchasing “hard copy” materials. I think that with liner notes you can get a good foundational knowledge from which to learn and develop a deeper understanding of the artists and the music.

I tell them to use the internet to research the artists and the music they like, and this will usually lead to other discoveries. If they read that one person that they like was greatly influenced by someone else, then they should seek out that person’s work, and then, like dominoes, follow the leads and see where it takes you. As an example, when I was much younger, I loved Chuck Berry‘s music. I read that he was greatly influenced by Elmore James and Louis Jordan. I followed those leads and it led me in two very different directions. On the other, I got into the blues. At the same time, I was listening to ragtime and learned of Eubie Blake. I read up on Eubie Blake and started working forwards from there. Eventually it all converged and “the bigger picture” emerged. YouTube can also be a good source of performance videos, interviews, etc.

I would also ask them what other kinds of music they like, and try to get them to name specific artists so I can get a sense of what they like and point them to things they might find interesting. For example, if a Jimi Hendrix fan wants to explore jazz, I’d point them to the Gil Evans/Hendrix disc. If they enjoy classical music I might point them to someone like Maria Schneider… or Jacques Louissier.

For those wanting a deeper dive: I would point them to some of the foundational folks: Armstrong, Ellington, Parker, Coltrane, Davis… always a good starting point. I would urge them to go and hear LIVE music and would point them to specific clubs and venues in their area. I would suggest that they explore some of the courses offered at local universities if they want to take a formal course, say, on the History of Jazz.”

- Tim Masters, Jazz radio host: Jazz Masters/Thursdays 8-10pm WPFW 89.3 in the DMV (livestreamed at wpfwfm.org)

“First I’d ask them if they played an instrument and which one if they did. If not, what instrument speaks to them the most from what they’ve heard already. Are they into music at all? As far as reading material, I’d probably give them [pianist] Hampton Hawes [autobiography] Raise Up Off Me” and then when they’re finished, play [Hawes’] “Blues Enough”. Depending on their age, let them read back issues of [the periodical] Straight No Chaser back issues or current issues of [periodical] WaxPoetics.

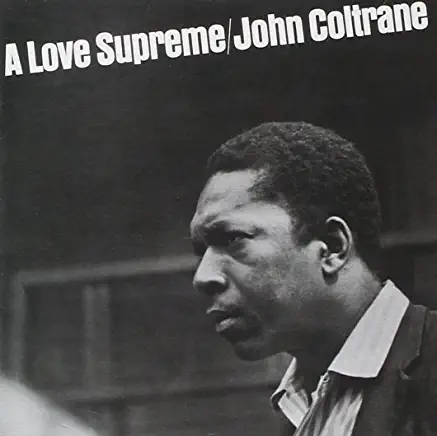

Cannonball Adderley‘s “Mercy, Mercy”, Trane’s “Love Supreme”, Betty Carter‘s “The Audience With Betty Carter”, Ahmad Jamal‘s “Jamal Plays Jamal”, Rahsaan Roland Kirk‘s “Bright Moments”, Charles Mingus‘ “Oh Yeah”, Miles Davis‘ “In a Silent Way”, and “Water Babies”, and Horace Silver‘s “Song For My Father” would be in a playlist. And then I would ask them what spoke to them from that playlist. But you should also be ready for the result that the person just might not be moved that way by music or in particular, jazz, though with so much diversity in jazz over they years, I’m sure there is a genre or period or artist that will speak to them.”

- Brian Michel Baccus, Producer/Curator/Consultant

Find a trusted jazz mentor and form a peer group

First jazz record: Miles Davis Kind of Blue

First Jazz books: The Story of Jazz (Marshall Stearns), Jazz Styles: History and Analysis (Mark Gridley)

Jazz Radio Stations: WBGO, WRTI (at night)

Jazz publications: DownBeat; JazzTimes; Jazziz; Hot House Jazz Guide

National Jazz Venues: Jazz at Lincoln Center; SFJazz

Jazz Record Store: Jazz Record Center (NYC)

Frequent as many live gigs as you can. Subscribe to a musician’s website. Use YouTube…

- Eugene Holley, Jr., Journalist

“Listen to John Coltrane, A Love Supreme“

- John Gilbreath, Earshot Jazz (Seattle, WA)

“It depends on where they are coming from. It also depends what they want: perform on pro or amateur level, learn more to listen and expand their knowledge. I’d first send them to a local show and/or jam session that I think is good. The first thing is to show the sense of culture and community around the music. It has to be a part our lives. Then whatever they have heard, I give them more of that or whomever is the person that inspired that artist. If they like Beyonce, I’ll play her scatting and with her horn section and then go down the list of gospel and R&B singers that do this and hit on our wonderful scatters. Then I’ll point out riffing and say that’s the blues and play Dinah Washington, Robert Johnson, George Benson…

I want them to find their own path that services their needs but keeps them involved in the community as much as possible so it’s not just a music of the past, but music of today.”

- Alison Crocket, vocalist-educator

“When I was young, there was a show on Sunday afternoons in New York, Dial M for Jazz. It was hosted by this guy who was a priest and they called him the jazz priest. It was pure luck that I tuned into it when I was about 12 years old and saw Wes Montgomery playing. I was dazzled by his style and his amazing proficiency on the guitar. But to me, it was all about the feel of the music and that’s how I would approach it with a younger person. [Wes]’s trio was fantastic.

It’s all about the feel between the musicians that played the music. Albums like Kind of Blue where the interaction between the musicians is flawless, and yet so melodic and hypnotic, it can take anybody to the right place ad get them into jazz. Another album that really had an effect on my was Ahmad Jamal Live at the Pershing Room. I heard “Poinciana” once, and was totally hooked and looked for rhythms like that, because it was totally funky and intoxicating for its time.

So what am I saying? I think you keep it simple and something that feels good and that a young person can feel inside… nothing too far over their heads. That comes as they understand the language more, but the most important thing to me is that they feel the music and they feel this is something that they could build on.”

- Jason Miles, musician-bandleader-author

“The most important thing a student can learn if they want to participate in any musical genre is about its history and evolution. All genres – especially jazz – are borne of cultures and evolve in relation to those cultures. If you play, simply knowing the mechanics and theory behind the music is not enough. You have to be aware of how the music functions and communicates with its audience. You have to understand the culture.”

- Eric Gould, pianist-composer-educator

” I would first ask them what music they like, and then draw from there what streaming platforms they use. Let’s say they like Kendrick Lamar and then point out about the jazz musicians who work with him and then trace roots to Herbie Hancock, Miles, etc. Point them to a general jazz Spotify list for jazz, show them videos of people their own age performing jazz, show them percussive and melodic jazz (i.e. “Manteca”, “Caravan”). Show them how jazz is a social commentary of today – Max Roach, Samora Pinderhughes, Terri Lyne Carrington… Take them to see a jazz show.

I had a friend who is 30-something who was not into jazz until I took her to her first live performance, which was Emmet Cohen with Houston Person. She fell in love with Emmet but also couldn’t believe that Houston was 88, and then dug in to finding more music by Houston.”

- Lois Gilbert, JazzCorner

“I would have them (as I do) listen, listen, listen… to 1950s jazz. The Modern Jazz Quartet, Chet Baker, Lester Young, Miles Davis (before Kind of Blue), Brazilian jazz, etc. I personally think 1949-1959 is one of the greatest periods in jazz… if not the greatest! We seem to have gotten away from (and I am including myself int there as well) listening as a teaching tool. “Classic jazz” still resonates with interested young people. I think listening should come first, then books, technique and theory should definitely come later. Listening is hard…”

- Paul Carr, saxophonist-educator-producer, Mid-Atlantic Jazz Festival

“If we are talking about getting, as you described “…a ground floor sense of what jazz is”, including an understanding of “its evolution”, I would put together an objective listening list that represents main jazz eras and styles, regardless of my, or this imaginary person’s “musical preferences”. I do not think that any potential listener needs “courting” or “enticing” to get into jazz and fall in love with it. I firmly believe that jazz has a compelling beauty of its own that does not need to be “sold” or “forcefed”. Representative of the eras and styles (from the top of my head) of jazz and its evolution are:

Black spirituals; Jelly Roll Morton, Bessie Smith, Mahalia Jackson, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Bud Powell, Dexter Gordon, Oscar Peterson, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey, Kenny Dorham, Thelonious Monk, Clifford Brown, Cannonball Adderley, Carmen McRae, McCoy Tyner, Eddie Jefferson, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Gil Evans, Elvin Jones, Horace Silver, Max Roach, Sonny Rollins, Freddie Hubbard, Betty Carter, Randy Weston, Ornette Coleman, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Pharoah Sanders. This could probably include a specific tune or album attached to each artist.

Instead of “reading about “jazz” per say, I would encourage them to first and foremost get a grasp of the culture and history of those who created this music, and those who continue to create it; meaning sociological, psychological, cultural aspects of where this music came from. Deeper understanding of African American history enhances the listening experience of a person trying to get to know this unique music form and decode what lies between the lines.

I would recommend reading the following books: Blues People by Amiri Baraka; African Rhythms composed by Randy Weston/arranged by Willard Jenkins; Why Black Men… by Rajen Persaud; Ain’t But a Few of Us edited by Willard Jenkins.

I would recommend staying away from major jazz venues, major jazz magazines, radio and TV programs, as well as major jazz awards and competitions in this present time because I don’t feel that – for an un-informed new listener – they reflect the best of the best; but in a sad majority of cases, the lineups and playlists cater to whomever has the most aggressive agent, or the musician with the highest number of Instagram followers, and so on. Live and recorded jazz music chosen for the true genius and talent of the artist, but [instead] by their so called “draw power”. So I would not advise anyone who is trying to get to know jazz for the first time to try to do it through current jazz magazines and other outlets, jazz clubs, and festival rosters, and so on. Thank goodness, there are precious exceptions in the media and industry who still treat jazz with actual integrity. However in my view, there “ain’t but a few of you…”

- Billy Harper, musician-educator

“Listening shouldn’t be and need not be hard. It should be fun. If you’re trying to transcribe a solo, count intricate polyrhythms, identify harmonies… it may be difficult due to the complexity of materials, but listening is not intrinsically harder than seeing, touching, smelling, tasting… Like those senses, it may be a skill that can be refined. But open your ears and sounds are everywhere. Now make some sense of them.”

- Howard Mandel, journalist-critic (Jazz Journalists Association)

“I would just say be aware and listen and be ready for surprises. I grew up in a non-jazz household, so my love of music came from listening to ’60s AM pop radio (waiting for the next Beatles single to arrive). I found that what I loved most about my local station was that it would fill in one-two minute segments of instrumental music at the end of each hour to be right in time for the news at the top of the hour… just snippets, but I was fascinated… then on to Chicago Transit Authority [later known as simply Chicago] because I loved the horn arrangements; then on to prog rock like Yes (lots of twists and turns) and especially King Crimson (what an ear-opener on its debut [album] In the Court of the Crimson King, with the title song full of jazz/free jazz/classical/psychedelic rock)… So my ears were open beyond the acoustic guitar time frame for me and as I went to college the free-form FM stations always played instrumental cuts (i.e. jazz, though I did not know what it was called then) within a set list that included lots of rock (Jimi Hendrix, Yardbirds, etc.).

In search of good music, I went to local clubs including the Rusty Nail in Hadley, MA where I was introduced to NRBQ, which again opened my ears when they played their rock built around jazz renditions of Monk and Sun Ra tunes.

Again, I’ve used the term “opened my ears”… that’s the key element… listening and being open to the newness that jazz offered even in the midst of the rock world.

When I moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, for my first years living south of Hollister the only radio station I could listen to was KFAT, where I learned a ton about country music. When I moved to Berkeley, my new music friends there had radio shows with an eclectic mix that included lots of jazz… I started following their leads and I began consuming music that I was attracted to… Dave Holland, Charles Mingus Miles Davis, Mahavishnu Orchestra… and it all grew from there… from listening a lot, then reading in the local papers about jazz and eventually starting to write for those papers about jazz artists coming to town and the burgeoning local jazz scene led by Peter Apfelbaum (who befriended Don Cherry who was living in SF and opened the door for me to interview him) and the just-launching Charlie Hunter. Listening and then experiencing jazz live fueled my organic sense of loving the music and insatiably reading about it and its history… graduating from Jazz 101 to a post-masters in the music, and surrounding myself with the new music, especially at festivals – from Monterey to Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy, to Cape Town, South Africa, to Beijing.

My advice in short… keep your ears open and seek the mystery of jazz in whatever music-loving environment you are in… even some of the top Grammy-winning pop stars have their ears open, and some even discover the life force that jazz offers.”

- Dan Ouellette, journalist-author

“Being a Motown baby, I found the classic CTI recordings from the 1970s was a great segue into jazz (Freddie Hubbard, Stanley Turrentine, George Benson, Hubert Laws, and of course Randy Weston…)

There is something about the sound and groove of those recordings that was quite attractive and compelling for someone growing up steeped in R&B, soul, etc… I also agree one must know about the history and cultural aesthetic of any art form to truly appreciate its existence. Dr. Billy Taylor’s Piano Jazz book is a great addition to anyone listening to jazz for the first time. Also anything by Amiri Baraka is quite valuable. There is also another book on John Coltrane which focuses on the parallel correlation between jazz’s evolution and the social/civil rights movement in the USA.”

- TK Blue, saxophonist-educator

“I think many of the jazz greats like Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, John Coltrane and so on are important, but if I were to recommend, I’d think out-of-the-box to unique women in jazz [who] bring about a view and understanding of the term “force-of-nature” is viscerally revealed in a quite profound manner. I was introduced to Betty Carter, Cassandra Wilson, Linda Sharrock, Abbey Lincoln, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Sarah Vaughan and so on – these quirky, intelligent, gifted women bring about a feeling of creativity through personality, audience engagement and performance that can inspire a rounded flash of fresh identity.

I think in 2023, documentaries are important; I would recommend young people choose any artist and explore live performances via YouTube, and stream documentaries to learn history. Then explore libraries for books to get an in-depth understanding of jazz history and the lives of artists would inform and create deep analysis and knowledge. I have ben teaching about the learning process more than specific artists, eras and materials so young people can dive in with a sense of freedom, and self-guided discovery.”

- Jordannah Elizabeth, journalist

“I’d do my best to hip them to great music being made by their generation, then let them find their way back up the many tributaries to the historical river of jazz.

Here’s a very short list (and no disrespect to any name left off): Lakecia Benjamin, Gerald Clayton, esperanza spalding, Cecile McLorin Salvant, Melissa Aldana, Shabaka Hutchings, Veronica Swift, Jose James, Kamasi Washington, Ambrose Akinmusire, James Brandon Lewis…

Let them see this music isn’t a museum piece. It lives, breathes and grooves with everything that’s happening in culture today. They need to see themselves in this music – their age, style, and sensibility – the same way we did coming up and the artists we sought out.

On reading I’d suggest DownBeat is a great place to start!”

- Frank Alkyer, Editor & Publisher, DownBeat Magazine