Following the pandemic of 2020, when most if not all jazz festivals were forced into a brave new “virtual” world (if not outright cancellation), in 2021 many such events returned as either shadows of their traditional design, in abbreviated fashion, or in different configurations as we crept back to normalcy. Such was the case with the 2021 edition of the Monterey Jazz Festival. Whereas the traditional Monterey County Fairgrounds setting offered not only the big venue Arena – home to the Jimmy Lyons Stage – but also the outdoor Garden Stage, Courtyard Stage, and adjacent Coffee House Gallery, and the indoor venues known as Dizzy’s Den and the Nightclub, as well as an indoor venue used to screen simulcasts of Arena performances.

Following strict pandemic precautions, the 2021 edition of MJF was a cautionary modest return with performances limited to strictly outdoors, which restricted the festival to its two main stages: the Arena and the Garden Stage, plus the Courtyard Stage, a patio amongst food service merchants just steps from the festival’s main entry gate that generally features emerging artists offerings. For the 2022 MJF that scenario was expanded to include a new outdoor stage adjacent to the old Dizzy’s Den building, known as the West End Stage, which opened up the Fairgrounds to more of its traditional configuration, though lingering local pandemic precautions continued to mean no indoor performances and limitations on the number of food and craft vendors, which meant frequent traffic jams at fan favorites among the tasty offerings. But what is always most consistent about any Monterey Jazz Festival experience – performances ranging from notable to memorable – happily persisted in spades this year.

One of the most notable of several MJF debut performances was delivered by the remarkable 24-year old vocalist Samara Joy. Mature of voice well beyond her years, Ms. Joy was on the cusp of her recently released Verve debut Linger Awhile. Her comfort level with selections from the Great American Songbook, her smooth phrasing, and simpatico with her band – particularly the fine guitarist Pasquale Grasso – was delivered with such elan that folks were overheard marveling at her artistry all weekend.

Other notable MJF debut performances were turned in by the Richmond, VA-based unit known as Butcher Brown, which brings a modern groove oriented crossover perspective as much informed by various fusion era incarnations as by classic hip hop. Butcher Brown drummer Corey Fonville and bassist DJ Harrison also contributed indelibly to Kurt Elling’s highly charged new project Superblue. The catalyst for this modernist update on the vocalist’s approach is decidedly the resourceful guitarist Charlie Hunter, who recruited the young cats who propel this project, including the Huntertone Horns (which notably included ace trumpeter Kenyatta Beasley) who give the project an essential brass uplift.

Guitar master Dave Stryker, who talked wistfully about his 2020 MJF debut having been obliterated by the pandemic, delivered quite soulfully to a deeply appreciative audience who seemed to share in his sense of something missed-then-recaptured. Stryker was joined by a wonderfully communicative unit that included Howard University’s own McClenty Hunter on drums, Hammond B-3 ace Jared Gold, and Warren Wolf on vibes.

Speaking of the vibes, Joel Ross and the enormously gifted saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins joined pianist-keyboardist Gerald Clayton for a set introducing the pianist’s bristlingly creative new vibes trio. Clayton, the artistic director of MJF’s Next Generation Jazz Orchestra, a national high school all-star band, put the young musicians through their paces for the Sunday afternoon opening set, counting off the set in high blues form with Thad Jones‘ infectious arrangement of the soulful Jerome Richardson tune “Groove Merchant.”

Other emerging artists who contributed notably to MJF ’22 included the pianist-composer Kris Bowers, himself a former Next Gen JO participant. Bowers was commissioned to write what resulted in the majestic, through-composed orchestral work “Asylo” in celebration of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Accompanying the sumptuous performance were big screen video of life among the majestic whales, including the lapping waves and calming seascapes. On the Garden Stage the youthful energy source known as Matthew Whitaker delivered his keyboard-fueled feel-good ouevre to great effect, making plenty of new enthusiasts along the way. Harpist Brandee Younger broadened Ravi Coltrane‘s Cosmic Music spiritual love letter to his parents Alice & John.

Photos: Courtesy of Bridget Arnwine

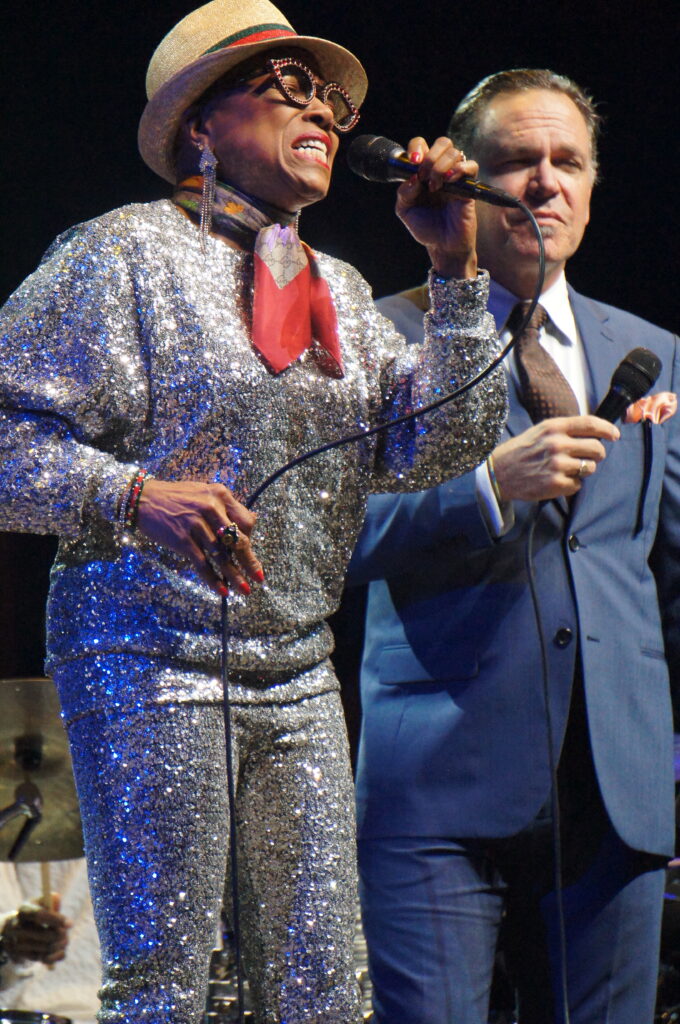

One of the true presences at this year’s festival was provided by the deep soul voice of Lisa Fischer, guesting marvelously with the blue rootsy band Ranky Tanky. This year marked a new iteration of the every 3 year touring assemblage known as MJF on Tour. In celebration of the festival’s 65th anniversary, artistic director Tim Jackson brought together Kurt Elling, Dee Dee Bridgewater (and you know that pairing will be fun on tour!), alto sax powerhouse Lakecia Benjamin, and a rhythm section of pianist Christian Sands, with bassist Yasushi Nakamura and the versatile Clarence Penn on drums. Sands’ MJF residency also engaged his “Sands Box” series of artist conversations, including a fun and stimulating Sunday lunchtime dialogue with Kurt Elling.

Nicholas Payton‘s set on the Garden Stage was one whose electronic intimacy might have been better – and more attentively – served in an interior venue. His trio – with two resourceful electronics manipulators who provided grooves and inspirations for Payton’s (too) occasional trumpet, acoustic bass, and keyboards. One of Payton’s mates was Sasha Masakowski, who too late in the set for my ears, finally unfurled her considerable vocal chops in service to Payton’s atmospheric explorations. But unfortunately the outdoor setting made for shifting audience dynamics.

One of the clear highlight small band sets was turned in by the masterful reunion quartet of Joshua Redman, Brad Mehldau, Brian Blade and the reliably buoyant Christian McBride. The levels of communication between these four was a constantly evolving revelation as they traveled the varied vistas of their compositions. Quite notable was their essay on Mehldau – who was on quiet fire all evening – composition “Mohawk”. Wouldn’t ‘ya know it, buzzard’s luck: this essential set was scheduled opposite The Cookers over on the Garden Stage! [Thankfully The Cookers do play the beautiful Keystone Korner Baltimore; in the DMV ya’ll; Joshua-Christian-Brad & Brian? Not so much…; thus the choice was clear.]. There were a good dozen more such conundrums throughout MJF weekend, and noting them here might prove painful, but such is life at the oldest continuing jazz festival on the planet.

The remarkable all-woman ensemble Artemis has added newcomers Nicole Glover on tenor sax and Alexa Tarantino to the core ensemble of pianist Renee Rosnes, drummer Allison Miller, bassist Noriko Ueda, and the always-rewarding trumpeter Ingrid Jensen. Their set provided further evidence of the welcome broadening gender perspective of our current jazz moment where high class women musicians and bandleaders are arriving on the scene in accelerated fashion.

One of the great moments of this year’s festival was provided by the veteran artistry of pianist-composer Chucho Valdes‘ broad canvas work “La Creacion”, a large ensemble work beautifully co-conducted by pianist-keyboardists John Beasley, whose ensemble Monk’estra horn section powered the work, and Chucho’s Cuban compadre Hilario Duran. With at times 3 ritual bata drum & voice contributors in the ensemble, this densely layered work will be on tour this Fall. The work included a beautiful calypso section keyed to one of the trumpeters in the ensemble, Trinidadian Etienne Charles, and an incendiary drum excursion from Dafnis Prieto. With Chucho’s bravura piano at the helm, this was the most inspired performance of this MJF edition.

Per usual, there were so many moments of musical conflict with great acts all across the Fairgrounds making it impossible to capture it all, that one should always approach a Monterey Jazz Festival experience with the thought that you just can’t catch all the great moments, so best to settle on your essentials knowing that you’re always going to catch more than a few surprises and be introduced to more than a few new artists to further enrich your pallet.

Photos: Bridget Arnwne