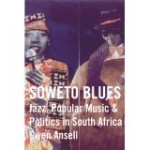

Over the last decade jazz in South Africa has been a source of endless fascination for this writer, on several fronts. Wondering how the music became such an indelible part of the anti-apartheid struggles and has continued to develop in post-apartheid South Africa was something I was intent on learning the first time I was blessed with an opportunity to make that long journey (17 hours by air to Jo’Burg from either New York or DC). In preparation for that trip as luck would have it Gwen Ansel’s deeply informative and lively 2004 book Soweto Blues (“Jazz, popular music & politics in South Africa”; pub. Continuum) came out just months prior to the trip.

Devouring that great book gave me a bit of a leg up on the whys and wherefores of jazz in South Africa. Then hearing the music in Cape Town at the Cape Town International Jazz Festival (assiduously avoiding most of the western artists presented on the festival in favor of the SA bands), and subsequently scarfing up CDs at excellent record stores on site at the festival, in Cape Town (including a good outlet on CT’s lovely waterfront mall), Johannesburg (ironically on the road to Soweto), and Durban (yes, they still have great record stores in SA, thank goodness), and online at the Sterns Music site, I was intent on producing a series of radio programs for WPFW in DC. Those subsequent shows became the subject of endless listener fascination; The calls still come whenever SA discs are spun.

Acquiring the records was only part of the task however. Through the graces of good friend Judy Pillay at the SA tourism office in New York who accompanied us on the trip, CTIJF founder Rashid Lombard, and Gwen Ansell (who annually hosts an extensive workshop for aspiring music print & radio journalists during the week leading up to the festival) I connected with several South African musicians for extensive interviews, none more informative or knowledgable than pianist-composer Hotep Idris Galeta.

A native of Cape Town, who passed suddenly in November 2010 at age 69, Hotep brought a broad perspective on jazz in SA. In addition to his work as a music educator and a player in-country (check his discs on the SA label Sheer), Hotep’s perspective was broadened by his world touring and recording experiences, with such artists as Hugh Masakela, Herb Alpert, John Handy, Letta Mbulu, Jackie McLean (Hotep also taught at JMac’s program at the University of Hartford), Joshua Redman, Archie Shepp, Elvin Jones, Bobby Hutcherson, Woody Shaw, and even David Crosby and the Byrds. Hotep and I developed a friendship from that first interview and he subsequently contributed the following piece to The Independent Ear. On the eve of the 2012 edition of the Cape Town Jazz Festival, I thought it would be a good opportunity to revisit Hotep’s wisdom on jazz in South Africa.

The Development of Jazz in South Africa

By

Hotep Idris Galeta

African music, the progenitor of jazz and all other forms of African-American music has been around for a while. Given its ancient track record of longevity and creativity, I suspect it will be around for a long time to come, molding and influencing the various genres of world music. From a historical point of view and in this particular case, the musical chickens have come home to roost. Jazz has come full circle returning to its African roots.

South African Jazz has had many elements contributing to its evolution and development. The most prominent and significant being the rich eclectic cultural diversity of the country’s inhabitants and the influence of African/American musical culture upon it over the years. These two variants coupled with an environment of legislated racism, gross human rights violations, created the unique artistic forge and mould responsible for the evolution of South African Jazz. The first informal contact the inhabitants of Cape Town had with African Americans was during the American Civil War, when the Confederate warship the “Alabama” came into the port of Cape Town in 1862 to replenish its supplies. The “Alabama” patrolled the South Atlantic where it would lie in wait for Union Ships to come around the Cape from the Far East on its way to the east coast ports of Philadelphia, New York, New Port and Boston. It would then attack, plunder and sink them. The “Alabama” was one of the most notorious and feared Southern commerce raiders on patrol in the South Atlantic sending some fifty eight Union vessels to the bottom of the ocean during her two year patrol. Confederate captain Raphael Semmes commanded this British built steam powered schooner.

A mixed crew of British mercenary and Southern white sailors manned the ship. On board there were also a small contingent of African-American slaves who served as cleaners, mess stewards and also provided some sort of musical entertainment for the crew. When the Alabama docked in Cape Town the local population flocked to the waterfront to look at her. It was then that the African-Americans dressed in their minstrel outfits gave impromptu musical recitals at the dockside where the “Alabama” was moored. When the inhabitants of Cape Town enquired from the white crew who the black entertainers were, the reply was “These are just our “Coons”! Or more succinctly put, “Just Our Niggers!

The Alabama was finally tracked down and sunk off Cherbourg, France by the Union Warship the U.S.S. Kearsarge on the 19th of June 1864. On June 19th 1890 South Africans had their first formal contact with black-Americans and Black-American music when the minstrel troupe of Orpheus Myron McAdoo’s “Virginia Jubilee Singers” from Hampton Virginia presented a series of concerts in Cape Town. Orpheus McAdoo was born in 1858 in Greensborough, North Carolina. As a young man he attended the Hampton Institute in Hampton Virginia, where he studied and graduated as a teacher in 1876. Before turning to music as a professional career in 1886 he taught school in Pulaski and Accomac Counties in the state of Virginia for ten years. In 1886 he toured Europe, Australia, New Zealand and the Far East after joining five members of the original Fisk Jubilee singers. Upon his return to the U.S. a year or two later McAdoo formed his own company by recruiting some ex students and graduates from Hampton amongst who were his future wife Mattie Allen and his brother Eugene. With his newly formed troupe consisting of six women and four men, they set sail on a European tour in 1888. Two years later we find them arriving in South Africa. Their appearance was to have a significant impact upon the music scene as it later influenced the creation and formation of the “Kaapse Klopse” or “Coon Carnival.” Since it’s inception at the turn of the century the minstrel street carnival became an integral part of Cape Town’s performing arts culture during the New Year celebrations. To use the derogatory term of the racist American, south of that time,“ Coon” or “Nigger” being the equivalent of the South African derogatory term of “Kaffir,” “Boesman,” “ Cooley” or “Hotnot”. If we look back to the Alabama’s visit to Cape Town we can now clearly see how the derogatory racist American term “Coon’ came to be known and adopted in Cape Town. Given South Africa’s colonial past of class consciousness, racism, divide and rule tactics, leaves little doubt for any speculation as to the name “Coon” and its tenure, popularity and longevity amongst the working class coloured population of Cape Town.

The “Coon carnival’s” popularity however decreased as more and more young people became politicized as the struggle for liberation intensified during the late 1970’s and into the 1980’s. McAdoo’s Minstrels stayed and toured throughout South Africa for eighteen months visiting places such as Grahamstown, King Williams Town and Alice where they visited and performed at Lovedale College, a South African equivalent of Tuskegee University. Musical history also indicates that their impact and influence upon the performing arts culture of the Eastern Cape was quite significant as it influenced the rich Xhosa choral traditions in existence there. It is somehow ironic that this genre of Creole/African/American minstrel-spiritual music which became one of the key developmental elements of jazz in New Orleans in 1895 should also become a contributing factor and play a crucial role in the development of South African Jazz. The introduction of Jazz into South Africa took place shortly after the 1st World War, around 1918 and this introduction was again via Cape Town. The first Jazz recording was only made in 1917, and this by the all white New Orleans Band called “The Original New Orleans Dixieland Band”. Some of these early recordings were brought to Cape Town by American merchant seaman. Local white and coloured bands (the Creole mixed racial population group resident in the Cape Town area) and even some visiting American musicians were instrumental in popularizing early New Orleans style jazz at the Cape after the 1st World War. To the white musicians who played it and the white audiences who danced to it in America and elsewhere in the British and European Imperial colonies it became known as Dixieland. Given the dreary social life and appalling conditions in the black South African townships, it is easy to understand why the introduction of the radio, gramophone and recordings of New Orleans Jazz served as the biggest catalyst for the developing styles of early township music and black professional musicianship in the 1920’s. It was in Queenstown in the province of the Eastern Cape that Jazz first developed and started to take on its South African character. Of all black people in South Africa at that time, the Xhosa nation were the most educated as the result of the early establishment of the British Missionary school system. Formal education, exposure to European hymnody and western classical music gave rise to a black upper class and a group of very sophisticated musicians and composers who embraced this new black American art form called Jazz.

In the 1920’s Queenstown became known as “Little Jazz Town” because of the many New Orleans style bands that were resident there. The most popular bands there in the 20’s and 30’s were Meekly Matshikiza’s “Blue Rhythm Syncopators” and William Mbali’s “Big Four” who entertained both whites and upper class blacks. Some of the earliest preserved examples of South African Jazz were recorded by Gumede’s Swing Band on Gallotone GE 942 in the late 1920’s. It was during the late 20’s that Boet Gashe an itinerant organist from Queenstown popularized the three chord system the forerunner to the Marabi and Mbaqanga styles that were later to be perfected in the township shebeen environments of Johannesburg and Marabastad situated on the outskirts of Pretoria. Sophiatown the legendary ghetto of Johannesburg became the experimental ground for this vibrant new township music that was to under go further innovation during the 1930’s into the 50’s. The music of the townships served as an important platform and vehicle for developing singers and instrumentalists. Larger 15 piece bands such as the “Jazz Maniacs” were formed by popular Doornfontein shebeen pianist turned saxophonist, Solomon “Zulu Boy” Cele. Cele who was listening to the African/American bands of Fletcher Henderson,Count Basie and Duke Ellington saw the enormous potential of developing marabi into a big band style. This band was to feature and develop some of the legendary township Jazz players. They included saxophonists Mackay Davashe, Zakes Nkosi, Ntemi Pilliso and Wilson “King Fish” Silgee. The Jazz Maniacs are significant because they carried the spirit of marabi to the dance halls and provided inspiration for a new breed of emergent Jazz musicians such as Dollar Brand now known as Abdullah Ibrahim, Hugh Masekela, Kiepie Moeketsie, Jonas Gwangwa, Sol Klaaste, Early Mabuse and Gwigwi Mwerebi. Some of the legendary Sophiatown vocal groups and singers associated with the “Jazz Maniacs” are the Manhattan Brothers, The Quad Sisters, The Woody Wood Peckers and a group that was to launch four great individual singers, The Skylarks, consisting of Miriam Makeba, Abigail Khubeka, Letta Mbulu and Mary Rabotaba. The demise of marabi big bands can be directly attributed to encroaching legislated racism, forced removals and regulations forbidding blacks to appear at venues where liquor was served.

As the dance halls in Sophiatown and other areas around the country were destroyed, black musicians were shut out of the inner cities or had to play behind a curtain when playing with some of their white counterparts at whites only clubs, Jazz was gradually being deprived of its multi racial audience.

The 1950’s are remembered as the days of passive resistance against the Nationalist government’s institutionalized racism, but it also remembered as a great age of Jazz development in South Africa. A new strain of Jazz began to emerge which contained a greater American influence. This new strain was the result of the Bebop revolution in the U.S. Young emergent musicians such as Dollar Brand, Chris McGregor, Johnny Gertse, Sammy Moritz, Makaya Ntoshoko Mra “Cristopher Columbus” Ngcukana, Jonas Gwangwa, Jimmy Adams, Early Mabuza, “Cups and Saucers” Nkanuka, Hugh Masekela, Kippie Moeketsie, Henry February, Anthony and Richard Schilder, Harold Japhta and this writer included took to this new exciting Jazz form from America like ducks to water. The real milestone occurred when one of my future mentors to be, visiting American pianist and Jazz educator John Mehegan came to South Africa in the late 50’s on an American State Department sponsored tour. After the tour he assembled a local group to record an album for Gallo Records entitled “Jazz in Africa”. Beside Mehegan on piano the group consisted of Hugh Masekela on Trumpet, Jonas Gwangwa on Trombone, Kiepie Moeketsie on Alto Saxophone, Gene Latimore on Drums and Claude Shange on Bass. When Mehegan departed for the U.S. Dollar Brand added Johnny Gertse on Bass and Makaya Ntoshoko on Drums, creating a new rhythm section to which he added Masekela, Gwangwa and Moeketsie, calling this new band “The Jazz Epistles” One of the most dynamic and creative bands of the late 50’s. The band recorded two albums “The Jazz Epistles Vol. 1 and Vol. 2” played a few gigs around the country and disbanded when Masekela and Gwangwa left to study in the U.S. in 1960. That unfortunately was the end of the line for that kind of American Jazz in South Africa. Many of the musicians who played it left the country because of the increasingly repressive political situation, this writer included. With the advent of the Avant Garde in the 60’s the “Blue Notes” led by Eastern Cape born pianist Chris McGregor together with saxophonist Dudu Pukwane, trumpeter Mongezi Feza, bassist Johnny Mbizo Dyani and drummer Louis Tebogo Moholo took up the banner and propelled the music in a new direction. They also had to leave the country but made a huge impact upon the European and British jazz scene with their fiery brand of South African Avant Garde Jazz. It is only Louis Tebogo Moholo that is alive today. The rest of them all died in exile before they could experience the freedom of democracy in the land of their birth. Many stayed and continued to produce creative music in a political environment that became increasingly oppressive and brutal.

In the province of the Western Cape in the city of Cape Town musicians such as Basil “Mannenberg” Coetzee, Robbie Jansen, Paul Abrahams, Chris Schilder, Gilbert Matthews, and many others to numerous to mention gave their commitment, time and creativity to the struggle for democracy. They used South African Jazz as a platform and became deeply involved in the struggle for democracy on a creative level using their music as a clarion call for liberation at United Democratic Front political rallies in the townships. Today in a democratic South Africa jazz is thriving in an environment of freedom and racial reconciliation. At present there exists an up and coming core of extremely masterful young musicians, both black and white. Some of them are graduates from tertiary institutions here in South Africa with vibrant jazz education programs and some come from community jazz education programs. Gloria Bosman, Judith Sephuma, Melanie Scholtz, Zim Ngqawana, Kevin Gibson, Andile Yenana, Lulu Gontsana, Mark Fransman , Eddie Jooste, Buddy Wells, Paul Hamner, Keshivan Naidoo, Dominic Peters , Andre Petersen, Victor Masondo, Marcus Wyatt, Herbie Tshoali, Themba Mkize and the late Moses Taiwa Molelekwa. These are just a few of some of the new innovative core of younger South African musicians who are responsible for taking the music into a new creative direction. Their vision and innovative approaches is creating a significant impact upon the South African jazz scene by the development of new concepts and ideas within the South African jazz genre. This bodes extremely well for the development of jazz in South African which like in Nazi Germany some sixty odd years ago had been suppressed and stifled during the turbulent apartheid era.

Copyright: by Hotep Idris Galeta

A good source of information on South African jazz musicians, and SA musicians in general, is the website www.music.org.za